Grand strategy, one way or another, almost always relates back to long term planning and strategic vision. But can a civilization without a word for strategy and grand strategy possess such a concept or practice in the first place? According to one of the most important and acclaimed scholars on modern strategy, the answer is yes. Rome had a comprehensive and intelligible grand strategy during the imperial era, despite never having coined a word for strategy, and its existence can be inferred by the cost-effective but also logical approach the empire took to managing its frontiers. Such is the argument put forward by Edward Luttwak in his highly provocative book, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire.

While looking at the obvious problem of devising a cost-effective way of securing the Empire’s borders for the long-term, Luttwak argues that the Romans intuitively adopted three great cost-effective grand strategies to meet their growing security needs. Important to the concept of strategy, as known to Luttwak and many practitioners, is the argument that each strategy’s ultimate goal was to provide maximum security benefit for the lowest cost.

Phase 1: The Client State System (Augustus to 1st Century AD)

The first great cost-effective strategy, or grand defensive strategy if you will, identified in Luttwak’s book is the Client State System, which was based on an invisible frontier of neighboring allied tribes and allied states. Once made a client to Rome, the lands of these allied tribes and allied states along Rome’s border acted as a buffer against foreign invasion, while at the same time their own forces contributed to lessening the overall defense burden on the Roman army for border security. With Roman soldiers free from extended garrison duties along the border, which were now being outsourced to the client states themselves, Rome had enough disposable force to seek new conquests elsewhere which, if successful, would ideally generate new client states. This positive feedback loop of continuing adding new vassals along the periphery of the empire inevitably generated economy of force for the Roman legions which then reinforced a system of manageable frontier expenses and efficiencies. Underwriting all of this of course, and keeping Rome’s clients at bay, was the unassailable quality of the Roman army at war and the near invincible aura of Roman prestige.

Phase 2: Preclusive Defense (Late 1st - 2nd Century AD)

Beginning in the late 1st century AD, changing political circumstances (such as annexation along the border and Romanization of the frontiers) meant Rome could no longer rely on the Client State System for border security. Faced with the new challenge of having to actually defend Roman citizens and the border provinces themselves, Luttwak argues that the Romans gradually adopted a second great cost-effective strategy in Preclusive Defense. According to Luttwak, the Romans once again sought cost saving measures for its limited number of legionnaires and manpower resources by purposely seeking out natural obstacles to foreign invasion: such as the Rhine, Danube, Arab and Sahara deserts, and the Euphrates river. When these “natural borders” however, were not available for conquest or just out of Rome’s reach, the Romans constructed limes and established garrisons, the most famous of which is Hadrian’s wall.

Phase 3: Defense-in-Depth (3rd Century AD)

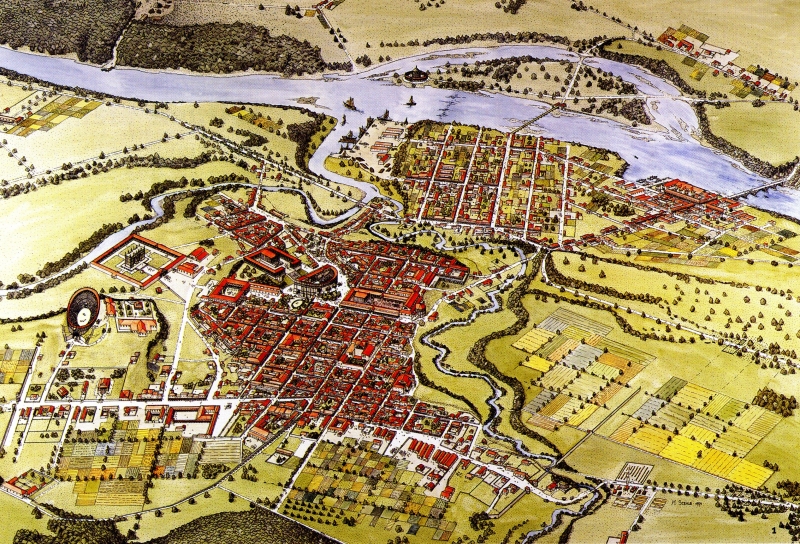

Western Empire Map Showing Distribution of Frontier Forces (Limitanei) and Field Armies (Comitatenses) 400AD

The last great defensive strategy identified by Luttwak is Defense-in-Depth. Here, Luttwak argues that multiple high-intensity invasions at multiple points of entry along the empire’s frontier made forward deployment of the legions and Preclusive Defense next to impossible, leading naturally then to the creation of fortified towns and mobile field armies in response. A thick Roman interior and an array of fortified towns and defensive strongholds along the way to Rome would then delay, contain, channel, and hopefully exhaust any barbarian invasions until a Roman field army could arrive. The shift away from Preclusive Defense however, along with the ensuing abandonment of most of the empire’s border provinces, is usually seen then as a desperate move on part of the Romans.

Luttwak, Historians, and the Charge of Anachronism

Despite seminal like work and an undisputable command of both military and national strategy, Luttwak’s views and depictions of Roman grand strategy are generally not accepted in academia. The most frequent charge of all, from both critics and published historians, is of course the charge of anachronism.

The charge is indeed accurate and compelling. For instance, there was no planning staff at the head of the Roman army. There was no formal demarcation of the Roman border. There were no “scientific frontiers” complete with imperial recognition for natural boundaries. Uniformed systems of defenses across all Roman theaters, along with identical roles for army units, cannot be found. Roman garrisons and military buildings equally served a civil and transportation function as well as defense. There were no strategy documents, accurate world maps, a general staff, or defensive whitepapers carried over from Augustus to Tiberius or Nerva to Trajan. And there never was any ridiculous 20th century notion of escalation theory, mobile defense, or defense-in-depth in the minds, plans, expansionist policies, and ad hoc decisions of the emperors.

Whatever grand strategies Luttwak thus found in his rigorous survey of the Roman Empire, they were not Roman strategies. Too many inconsistencies in both narrative and archaeological evidence disproves of the notion that any imperial plan or strategic vision —short of ideological expansion and the personal security of the emperor— ever carried over from one emperor to the other. And if sustainable economics and cost saving goals were really the concern of all charged with imperial strategy, then one should also address Rome’s political economy, which, far from balancing most government and economic systems with ends, ways, and means, stumbled on falteringly and unwittingly into ever increasingly expansionist policies and expenses until finally, the whole system collapsed. The need to extract surplus economic resources from the conquered territories to support the growing mechanisms of state —and the ridiculous cost of the Roman army— culminated in a redistributive exchange system that operated on a massive scale, and its size and expense defies normal economic logic. Underwriting the costs of the logistics, the Roman army, and infrastructure requirements, along with the economic greed of the elite, were of course costly government expenditures and subsidies.

Was there ever a Roman Grand Strategy?

If important parts of Luttwak’s thesis, such as defense-in depth, preclusive defense, and the client state system, cannot be supported by the available evidence, did the Roman Empire then ever have a grand strategy? Can strategic purpose not be derived from the long-term positioning of the legions? How then did the Romans deal with constant threats from Parthia and the Germanic tribes for the long term? And how do historians even begin to account for the remarkable efficiency of the Roman army. Can only 28 to 30 odd some legions really begin to guard and defend the entirety of the Roman Empire without strategy, resource allocation, and economy of force? And isn’t strategy practiced and learned intuitively anyway?

As wrong and imperfect as his thesis is, Luttwak does do for historians what they and their reductionist methods failed to do for themselves. It takes a generalist and systems approach to recognize the strategic environment and all its individual actors, and by avoiding specialization and a rigid selection of historical methods, Luttwak takes into account the entirety of the Roman world and all its security challenges. Yet this satellite view of Rome’s geography and security problems leaves Luttwak knowing more than the Romans ever did. In the Roman world, strategy, planning, and long-term systems thinking were in their infancy, not even close to the level of sophistication of a modern general staff, but present and far above their peers nonetheless. In his book, Luttwak shows how the Romans acted and responded intelligently to different problems, creating complex systems, allocating resources, establishing goals, and executing strategies and plans for provincial security. At their best, the Romans even combined military effectiveness with political astuteness. But Luttwak gives the Romans too much credit when he identifies consistent grand strategy narratives and not more precise regional-military strategies used to maintain order and maximize efficiencies in the various provinces. Rome, after all, was sustained through its incredible military commanded by military governors in administrative districts. The emperor decided where to put the legions and how many to allocate, but that was mainly it. Individual mandatas issued to Roman governors took over from there, followed by each governor’s own response and management style to specific regional challenges (of the areas he controlled). A permanent military presence (arguably without a peer competitor) is all that strategically carried over from one emperor to the next, and from there each Roman emperor generated his own policies and established his own priorities. However, without clear lines of succession, imperial policies as a whole remained largely immune to the possible benefits of strategic thought and long-term planning.

In end, perhaps the most important step still left unconcluded between Luttawk and historians then, is not what the Romans were able to do or achieve for the long-term, but the entire notion and importance of grand strategy.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote