It always sounds somehow more refined when it’s in German, doesn’t it? Without further ado,

The Greek Cinematography Critique

Hello everyone! In this thread I am going to be presenting some of the most important films ever produced in the Greek republic including cinematographers such as Theo Angelopoulos, Costa Gavras, Giorgos Lanthinos, Pantelis Voulgaris and others. It’s going to be interesting to those who want to get a little extra in modern Greek studies, people generally interested in cultural exchange and people who are interested to see a critique complete with social background information and commentary. Wherever possible, the OST of the movies will also be discussed. The critiques accompany historical pictures and colorized pictures from the Past in Color project.

The MovieCostas Ferris’ 1983 film Rembetiko relatively recently got a remastering (2004) so I will begin this thread by reviewing a movie based on the greek underworld of 1924-1960. This is a world full of migrants, drugs, crime, and songs. This movie is a hard to swallow critique of the greek society of the time, in the tradition of many greek movies, with some feminist undertones. It can hardly be categorized as a musical, or a feature film, which makes for a unique viewing. Rotten tomatoes give the movie an 89% positive review.

It’s plot revolves around the fictionalized life of Marika, a Asia Minor migrant rebetiko singer who finds herself running away from home, abandoned by her first boyfriend, working her way up from hashish dens and tavernas during the 30’s and 40’s to nightclubs of the 50’s, when the rebetiko became more mainstream in greek society. In the ending of the film, as many rembetes, Marika attempts a trip to America where the ‘Greek Blues of the Underworld’ were making an entrance in the American music industry of the 50’s.

The Social Context

Rembetika is a form of greek urban music with heavy oriental influences, an homage to the Ottoman past of the rembetes. Tracing its origins from the 19th century onwards, the rembetiko exhibits a range of musical traditions influencing its development, from the demotic folk music of mainland Greece to Byzantine church music to late Ottoman café aman music. It was certainly the music of the outcasts for its greatest duration. The songs are about love, loneliness, despair, migration and the diaspora, jail, hashish and drugs, women, misfortune and misery, social injustice, current events, the Aegean and its waters, fishing, the landscape, poverty, death, daily life, violence, mangas culture, and so on. The usual instruments include the bouzouki, the sintari, and the violin.

The rembetes themselves came from Asia Minor following the military defeat of Greece in Asia Minor, and the exchange of populations agreed on the Lausanne treaty (1923) that formalized the expulsion of millions of christian and muslim people from their homelands. Their integration to Greek society was difficult, and mostly undesirable from the native Greek population who exhibited great lengths of bigotry against them; many of the refugees, coming from a bourgeois background in the Ottoman empire, were debased and confined to an underclass that had limited rights.

Those with bonds in banks like the Bank of the Orient were forced to swap these for a dime on the dollar; women were pushed to domestic work in order to acquire Greek papers; other women, unsuited for domestic work, were diverted to prostitution, a common theme in the songs; pawnshops were set close to the first settling of the migrants in places like Chios, Crete, and Piraeus where the migrants were instructed to sell their valuables (whatever they still had) for cash. The manges and rebetes tended to live in or around Piraeus; they frequented the tekedes (hashish dens); many spent time in jail, either simply for performing their music, or for engaging in other criminal behavior, such as smuggling, theft, or smoking hashish.

Οι μπάτσοι μας μπλοκάρανε βρε Μάνθο, μας τη σκάσανε

άντε μάγκες στη δουλειά σας μη χαλάτε την καρδιά σας

The city of Athens itself seemed divided on the issue of the rembetes. Since 1880, the typical Greek music is based on the Italian melodrama that characterize the kantades and the Athenian songs of the era. The music cafes are also divided between the limited but more popular café aman and the more numerous café santan, further hinting towards the division between the working classes that enjoyed the oriental influences of the rembetiko and the bourgeois who maintained the western influences were more ‘moral’. Following 1923 and the exchange of populations, the rembetiko gains in popularity as the songs of migrants and workmen, with the piraiotic style gaining in overall popularity. It won’t be until 1936 and the fascist dictatorship of Metaxas that the songs will be completely banished as ‘impure to the third Greek civilization’ dreams of the right-wing in Greece. Of course, the rembetes survived the persecutions and their songs gained in political themes during the German occupation. During the fifties and the mainstreamization of the rembetiko, the Greek state cracked down on the outcast culture by arresting and shaving the mustache of the rembetes (a shame), and putting them to work in closely observed nightclubs.

The review

The music of the movie is exceptional –unless you are one of those people who think that oriental music is like listening to wailing cats, then you won’t like it – as is the research in the lyrics. Many of these songs survived today but their lyrics have been altered times over to eradicate political and social dabs; the movie provides the uncensored versions. If you’re interested in just the music, the album is uploaded to YouTube here.

The societal woes of the asia minor migrants are also faithfully described in the film, as is the mangas culture that surrounded them. If I can offer a critique, the relation between the rembetes and the police is downplayed a lot, avoiding the constant raids that the songs hint to. There’s only a scene where policemen actually crack down on rembetes, but then it shows how rembetes were also linked to the workers movement.

The acting of the film is what anyone would expect of a 1983 film yet there’s a little more emphasis on the drama for my tastes at points, since this movie also tries to bring a feminist critique of the rembetes man-oriented culture into focus. This is not necessarily bad, but I think a little on the nose and not entirely faithful to history.

The mangissa, Rosa Eskenazi

The story itself echoes the life of the Jewish mangissa, Rosa Eskenazi, a very important figure in rembetiko and a tough ass mofo. I was very happy to see that the protagonists refer to ‘Rosa’ in the film many times, particularly to hint at her success, but also her tragic death. Eskenazi allegedly died in a hospital and hastily buried in the village Stomio of Corinth with only a handful people in attendance. A decade after her death, some people crowdfunded to plant a marble slab on top of her grave signifying her name and her being an ‘artist’. Of course, her private life was deemed as shameful to fully disclose, involving the existence of a daughter Rosa might had abandoned in an orphanage when she travelled to America to record her songs with Columbia Records. Her distinctive style of dress also makes appearances in the movie.

Overall, I will give this movie a 4/5 due to its strengths, namely the music and social depictions of the migrant life, yet I was a bit put off by some melodrama moments. But that’s just me.

I hoped you liked this review!

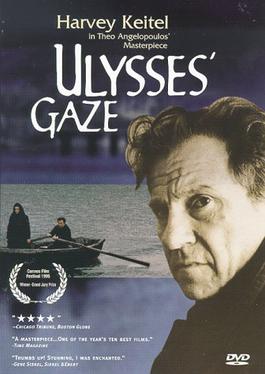

Next movie up will be Ulysses’s Gaze by Theo Angelopoulos.

The OST for the movie can be found here.