Re: [SS 6.4] KRONIKON TON BASILEION - Byzantine, Early Era, AAR (UPDATED CHAPTER XXV)

Re: [SS 6.4] KRONIKON TON BASILEION - Byzantine, Early Era, AAR (UPDATED CHAPTER XXV)

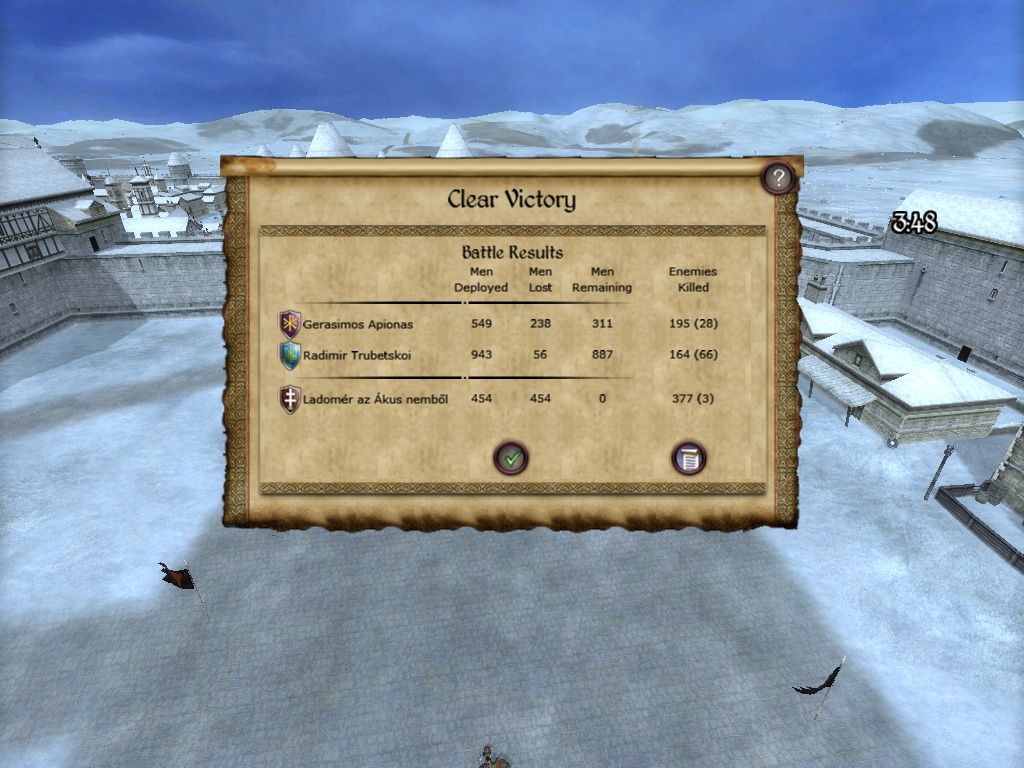

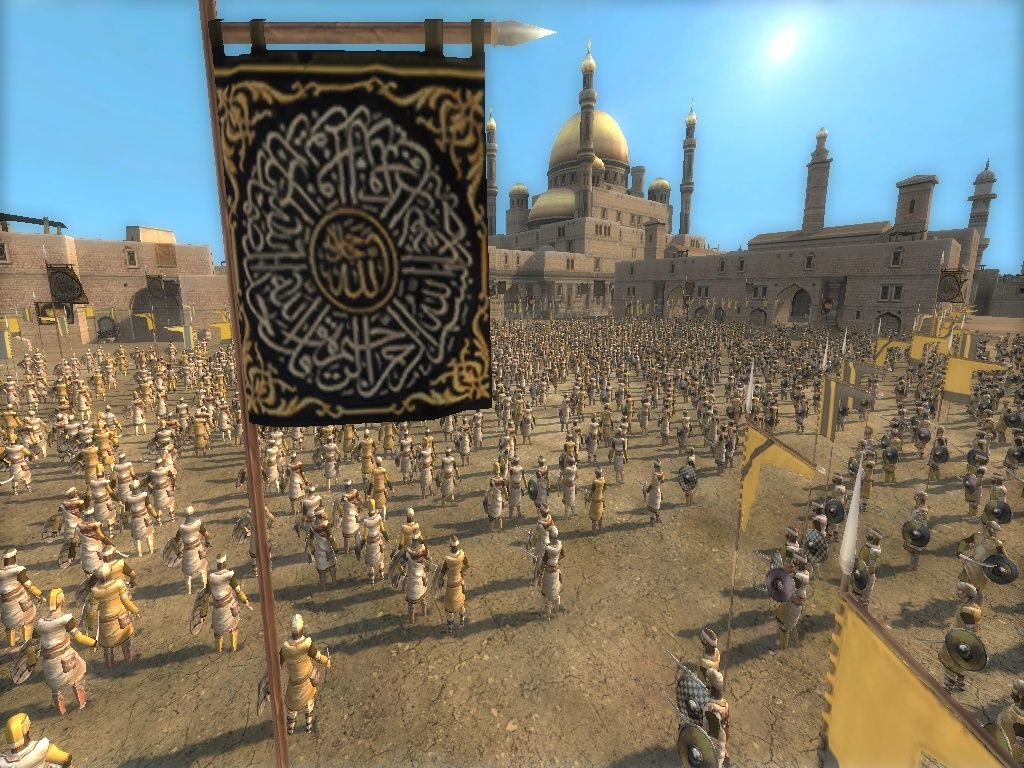

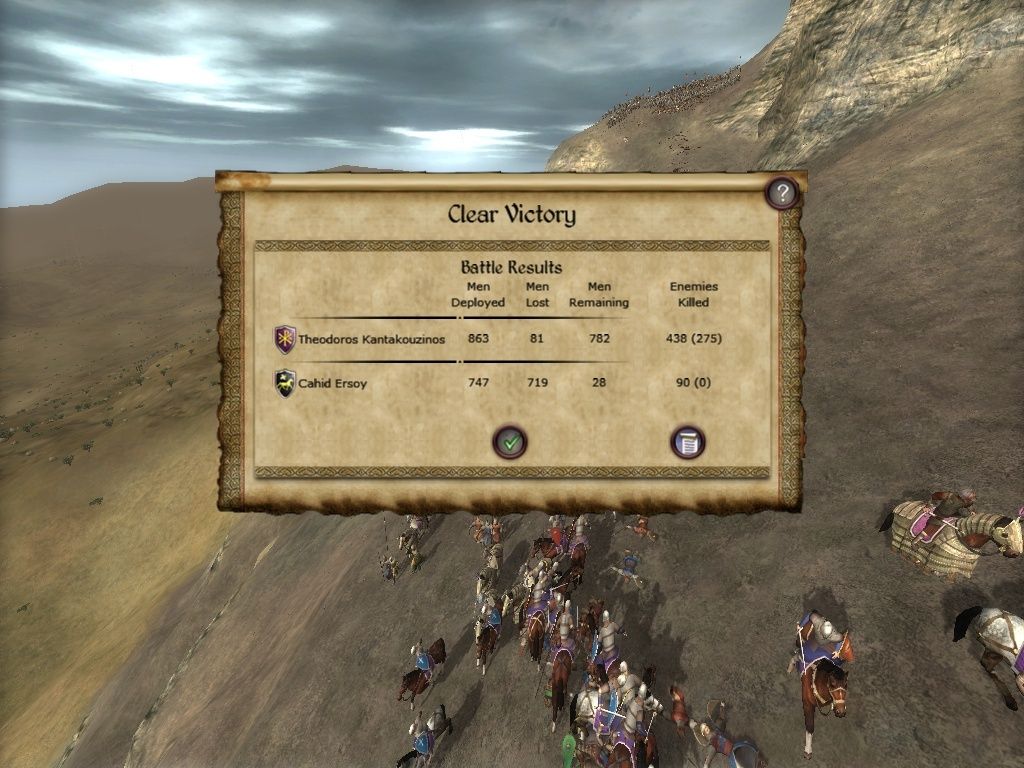

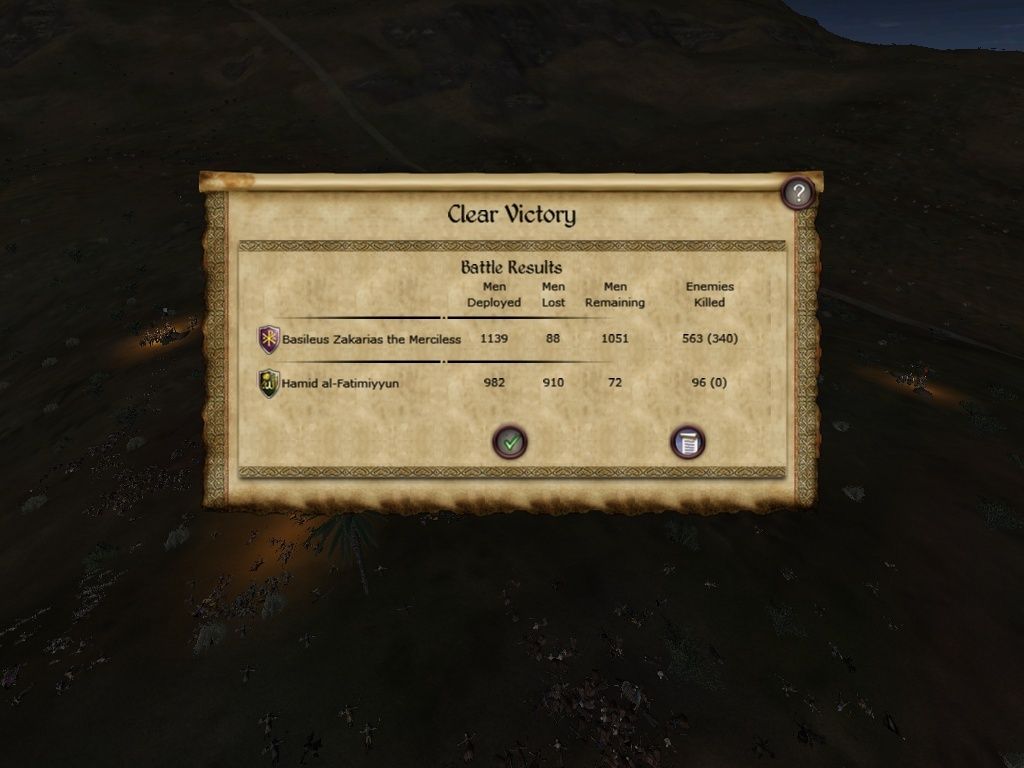

Great chapter and story-telling! I like the way that you begin with the cries of the unknown imam and tell the story of the brave defeat at Heraclea before moving on to the dramatic scenes of the battle on the plan of Nigde.

I found your initial comments about intolerance helpful. If we write authentic historical AARs, AAR writers will sometimes have our characters speak and act in intolerant ways. You are not the only AAR writer to feel concerned that some readers might misunderstand and think that we agree with the things our characters say and do.

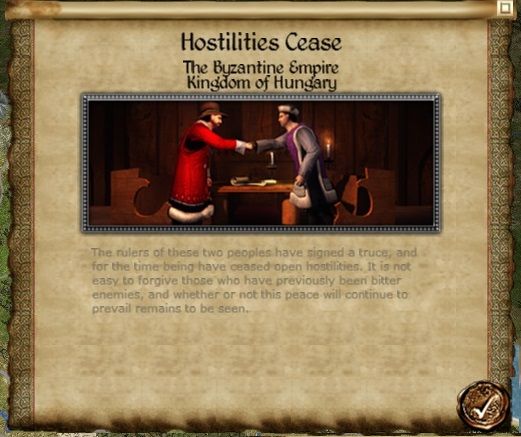

Yeah, I actually liked a lot writing about the Hungarian Civil War. I thought other factions needed some "characterization" as well. Also, it's really funny to me to write down the history of those factions, too. It's really amusing looking at the map, seeing how much have they grown/decayed and imagine a story to justify it all

Also, I think it adds personality to an already really, really enjoyable game...I've never cared so much about a single campaign. I love it.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

¨

¨