Salve, dear fellows!

The Bizantine Empire has always been my favourite faction in both Medieval and Medieval II; so, as my very first continuous playthrough with Stainless Steel, it seemed natural, to me, to play it for the Great City's glory and safety.

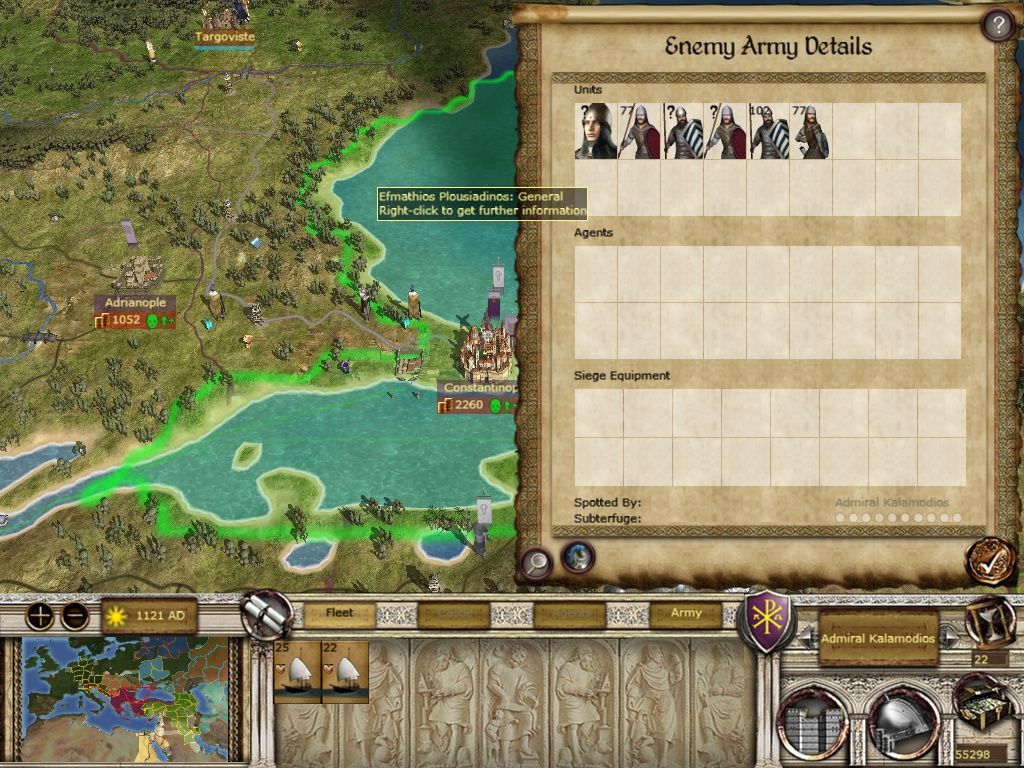

Home rules: H/VH ('cause the AI already gets enough economic bonuses!), Savage AI, Real Recruitment enabled, Slow Assimilation enabled.

Anyway, let's start!

Prologue - Uncertain Times

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:These are uncertain times to live. Empires crumble and fade as time goes by, adventuriers and warlords forge their own kingdoms with steel and violence. Several once mighty empires now are no more.

The Roman Empire has known defeat and humiliation, and its borders have been trespassed and occupied by enemies of every kind, its people have had to bend their kneel to foreign rulers.

The Empire its surrounded by enemies. And several more wait the right occasion to strike.

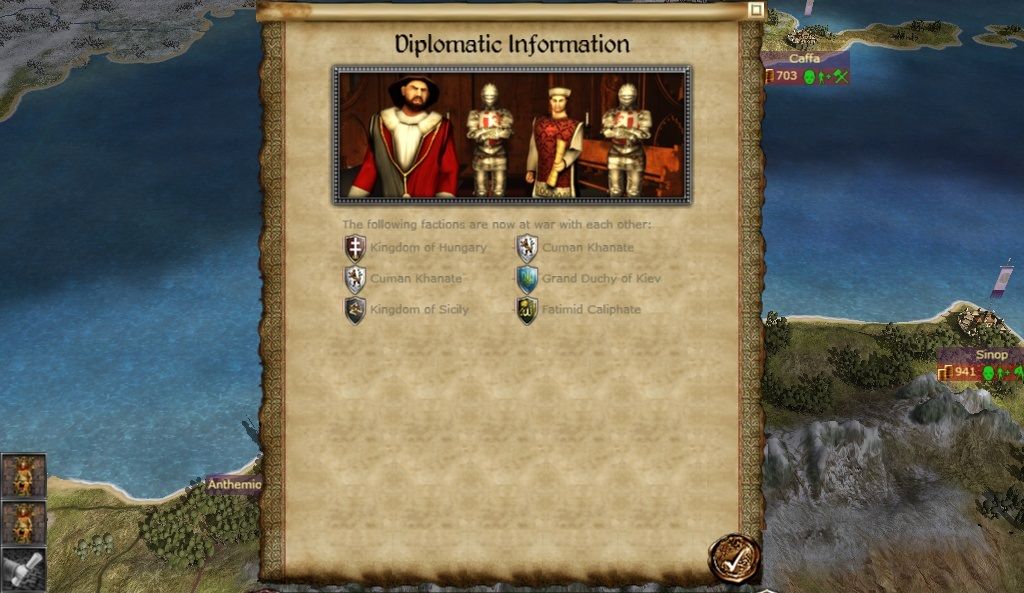

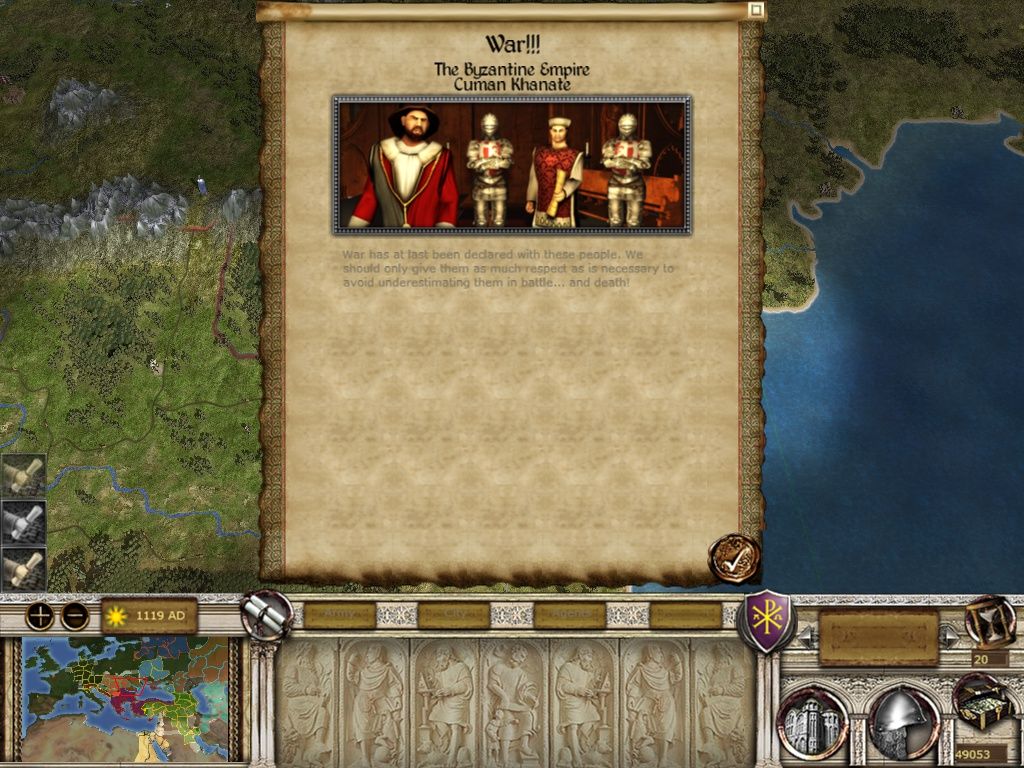

To the north, the Danubian provinces have been lost once again to the blood thirsty barbarians of the steppe. The war hungry Bulgarians have somehow rebuilt at least a part of their former strenght, and are now posing a costant threat on Costantinople's dominions in Macedonia and Thrace. Even further north, new nomad people have settled and streghtened their positions in the Carpathian region. The Magyars, one of the Empire's most proud and fearsome enemies, have settled in the wide hungarian plains and converted to Christ's word - although, the version proclaimed by the so-called Pope of Rome - establishing their own kingdom, the Kingdom of Hungary. To their east, lie the nomad pechenegs, alans and cumans, always ready to cross any border and eagerly sack, rape and loot at their leisure.

To the west, Italy has been lost to the Normans. They came in Italy as mercenaries in the struggle between the Empire and the Lombards, and later unified under the guide of adventuriers such as Robert the Guisckard. Under his guide, these capable knights and swordsmen have spoiled the Empire of its italian holdings, capturing Bari, the last byzantine stronghold in Italy, in 1071 AD. Furthermore, they have strenghtened, and now control all southern Italy, including the ancient and rich island of Sicily, from where they have been - and still are - ready to expand their dominions.

To the East, lies the greatest threat the Empire has ever faced in its History. Revitalised by the arrival of the Seljuq turks, islamic kingdoms have strenghtened their positions and inflicted bitter defeats to the Empire. However, the seljuqs warlords weren't satisfied with their roles as mercenaries and soldiers for these kingdoms; they have overthrown their arabian masters, taken control of the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, and started their own war of conquest against the Empire.

Seljuq Sultan Alp Arslan has inflicted Costantinople the worst defeat of its history, humiliating in battle and capturing Basileus Romanus Diogenes on the field of Manzikert, in 1071 AD.

The catastrophe of Manzikert, along with a long series of civil war, have brought the Empire on the edge of ruin. Anatolia has subsequently fallen to the seljuqs, and norman adventurier Robert the Guisckard and his son Bohemund have invaded the lands of Epeiros and Albania, taking a chance of the overwhelming chaos that had pervaded the Empire.

After bitter years of civil war, a new Basileus ton Romaion has arisen, Alexios I of House Komnenos. Although defeated by the Guisckard at Durazzo, Alexios' diplomatic and strategical ability, along with the Guisckard's death, have preserved greek rule over western Hellas, and pushed the invaders back to Italy. However, Normans and Greeks are far from establishing peaceful relationships: after his father's death, Bohemund has often troubled the Empire's peace, and right now, after the First Crusade, rules over the rich syrian city of Antioch, and hasn't yet forgiven his father's old enemies.

The Crusaders' advance into Anatolia has proved to be an outstanding occasion, to Alexios, to recover territories in Asia Minor and re-establish his rule over prominent cities such as Nicaea and Smyrna. The Crusade's success, and the Liberation of the Holy Sepulchre, have weakened the islamic powers and gave birth to the Crusader States of Antioch, Jerusalem and Edessa. Relationships between the Golden City and the frank Lords of Outremer are reasonably good, but in these uncertain times nothing is sure, and sharing faith in Christ's word isn't anymore a warrancy of peace.

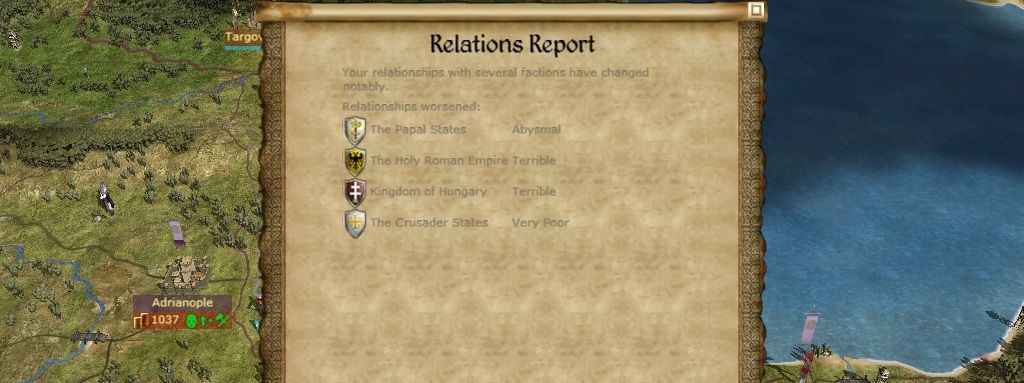

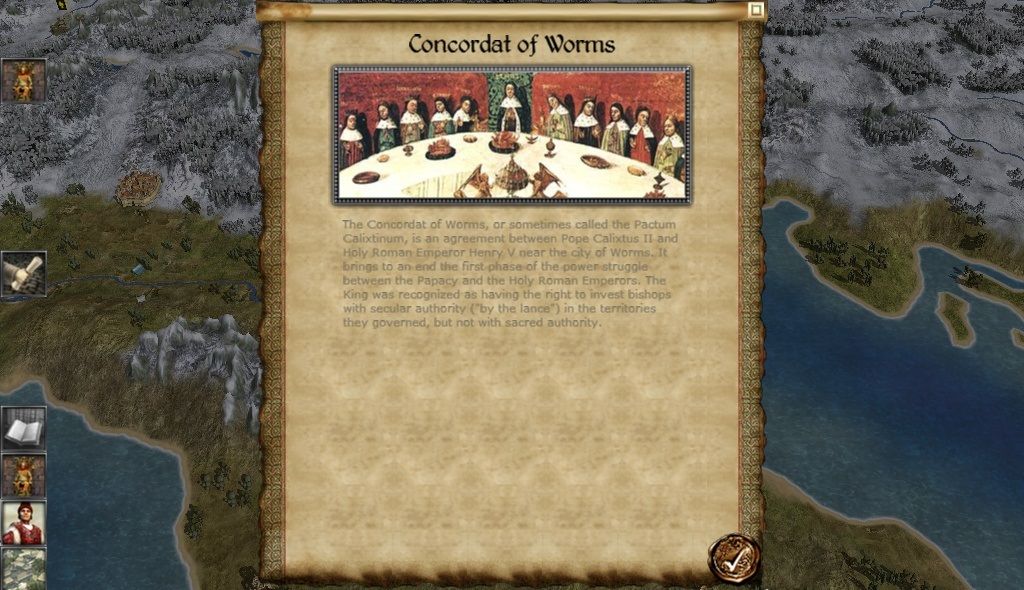

Perhaps the Empire's biggest threat, in fact, lies in its independence from Rome. Since the Great Schism, in 1054 AD, relationships between Costantinople and the Papal Seat haven't been easy, and many western lords and commanders don't hold in high regard what they perceive as the untrustworthy and unreliable schismatic Greeks. Some of them start perceiving Costantinople on par with other enemies of Christ, such as the Saracens or the pagans who still inhabit the lands of Prussia and Lithuania. The King of Germany still holds as his own the title of Roman Emperor, and the ambitious italian city states look with greed at the Empire's riches and resources. The Most Serene Republic of Venice, in particular, isn't to be trusted: a capable Basileus should keep an eye on those westerners, for they may give the Empire serious troubles if left unchecked.

The Empire's worst enemy, however, lies in itself, in the ambitions of the noble and selfish Houses that rule it. Even the Komnenoi family, after all, has arisen to the throne after a civil war, and Alexios himself has often had to deal with usurpers and traitors of every kind. The defeat of Manzikert has been triggered by the traitorious behaviour of Romanus Diogenes' enemies, and too often swords and steel, instead of law, have proved the key factor over the rise of an Emperor instead of another.

The Empire is surrounded by enemies, and it is in a critical moment of its history. Decay and downfall might be a footstep away. Yet, the Empire has managed to survive for centuries surrounded by its enemies, and maybe it still will: Goths, Alans, Huns, Vandals, Sassanids, Magyars, Bulgars, Arabs, Kievan Rus' and Pechenegs, all of them have laid siege to Costantinople, yet the Great City is still alive, while their legacy is lost or decayed. Maybe the Roman Empire isn't yet doomed to fall, by Christ's name - and Kyrie eleison.

List of Valiant Emperors and Noble Houses

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:BASILEI TON ROMAIOI

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Noble House Komnenos (1081-1260 AD)

House Komnenos arose to a major role in byzantine politics during the reign Basil II Bulgaroctonos, one of the most skillful and capable rulers the Empire had ever seen, in the person of its founder, Manuel Erotikos Komnenos. Manuel had distinguished himself in the defense of Nicaea against the usurpation of another of Byzantium's greatest generals, Bardas Phocas, and had been therefore granted by Basil himself of the lands around Kastamonu, in Pontus, House Komnenos' ancistral stronghold. His older son, Isaakios, was the first Komnenos to reign as Basileus. His short, yet brilliant reign ended, however, when he retired to monastic life after having been struck by a thunderbolt. His legacy, however, continued through his brother John Komnenos, whose son Alexios quickly earned an impressive reputation as politician and commander. In 1081 AD, Alexios rebelled against Nikephoros Votaniates, overthrowing him and taking the throne as his own. A new era had begun.

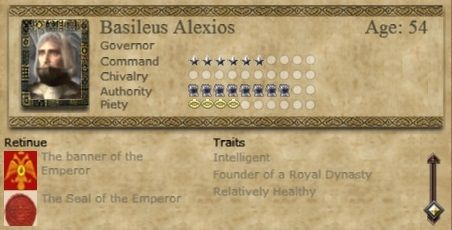

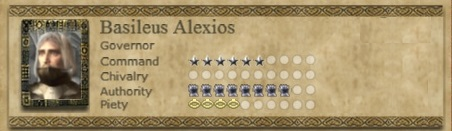

- Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1124 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

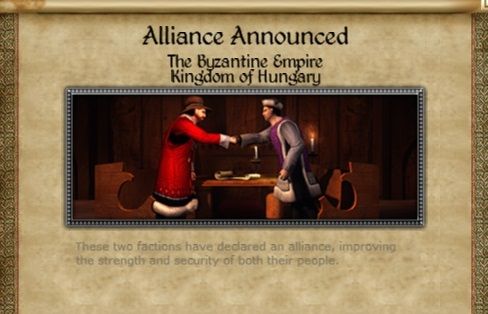

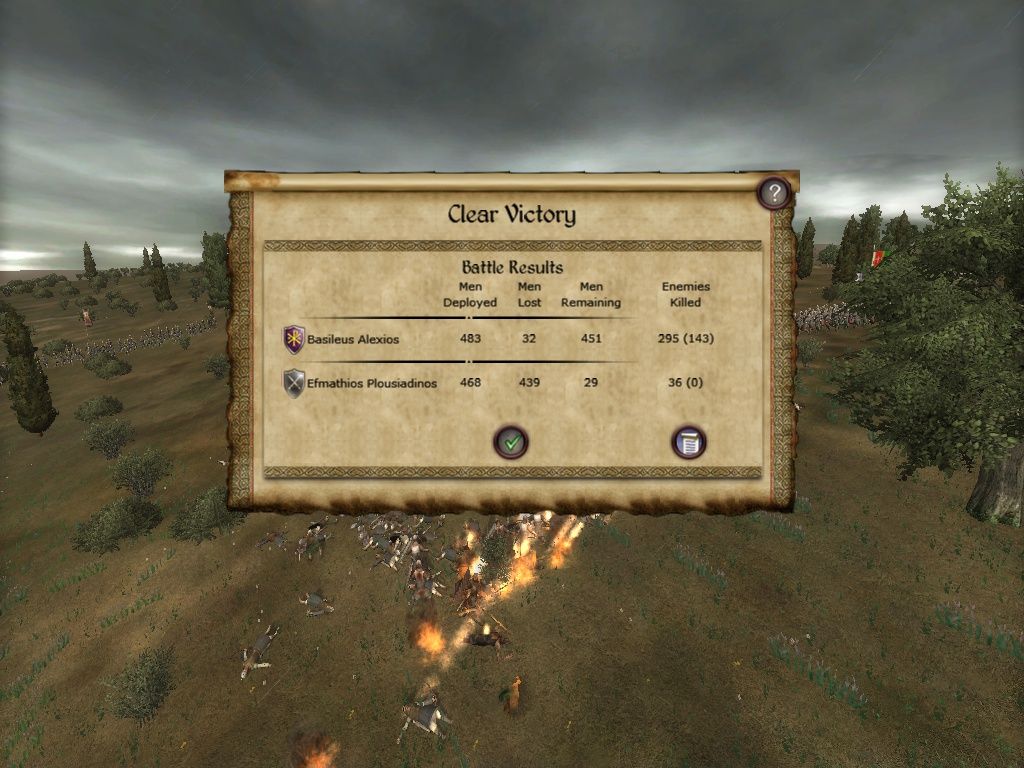

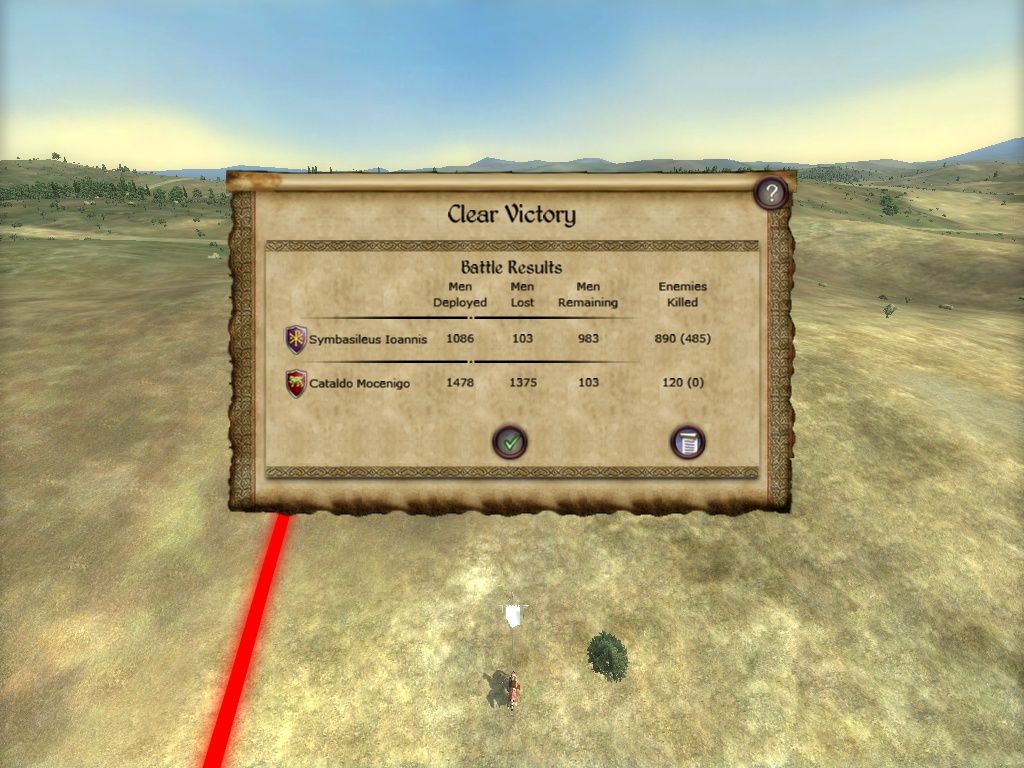

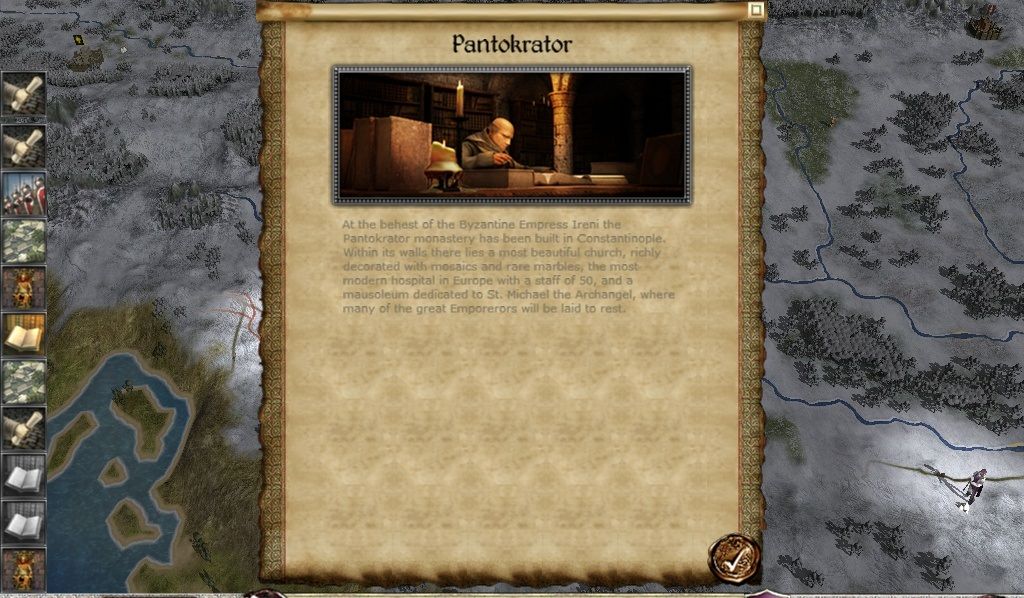

Arose to the throne in 1081, after a successful coup d'etat, Alexios I of House Komnenos played a key role in the recover of the Byzantine Empire after the bitter defeats suffered in the previous half of a century. During the First Norman -Byzantine War (1081-1085 AD) he somehow managed to keep at bay the growing threat posed by the Normans, who, after having seized Southern Italy, had invaded in forces Epeiros and Albania, led by adventurier Robert the Guisckard. Later on, thanks to a careful and skilled use of corruption, politics, steel and intrigue, Alexios I Komnenos not only managed to keep the throne despite the threats posed by several usurpers, pechenegs and the First Crusade, but also started what has been known as the Komnenian Restoration. Thanks to the help provided by the Crusaders, Alexios succeeded in the reconquering the Western Coast of Asia Minor from the Seljuqs which had invaded it after Manzikert; in 1103, the Basileus and his son Ioannis successfully invaded the Khanate of Bulgaria, restoring Roman rule over the danubian themas. He then forged alliances with Laszlò I of Hungary, the Kievan Rus' and the Crusader States. In 1110-1114 AD he led an anatolic campaign which ended with the recovery of the Black Sea coast. He then succeeded in repelling several Venetian attempts to overthrow him during the Second Crusade, and, through his son Ioannis Komnenos, supported Laszlò I of Hungary in his war with the pechenegs (1119-1121 AD), bringing Muntenia under Constantinople's control. In 1123, he defeated venetian crusading general Cataldo Mocenigo in the great battle of Adrianopolis, and founded the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople to celebrate the victories he had gained against the Normans, Bulgarians, Pechenegs, Crusaders, internal enemies and Seljuqs in almost 40 years of reign. He died the following year, unable to stop his sons to fight one against each other for control over the Empire.

- Anna Komnena's usurpation and Interreign (1124-1128 AD)

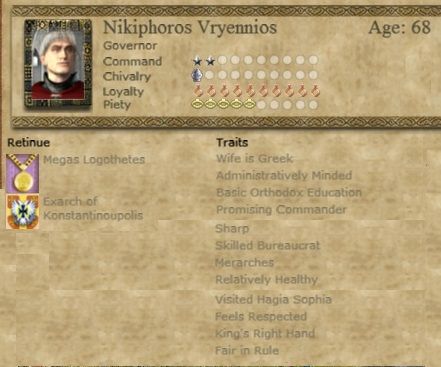

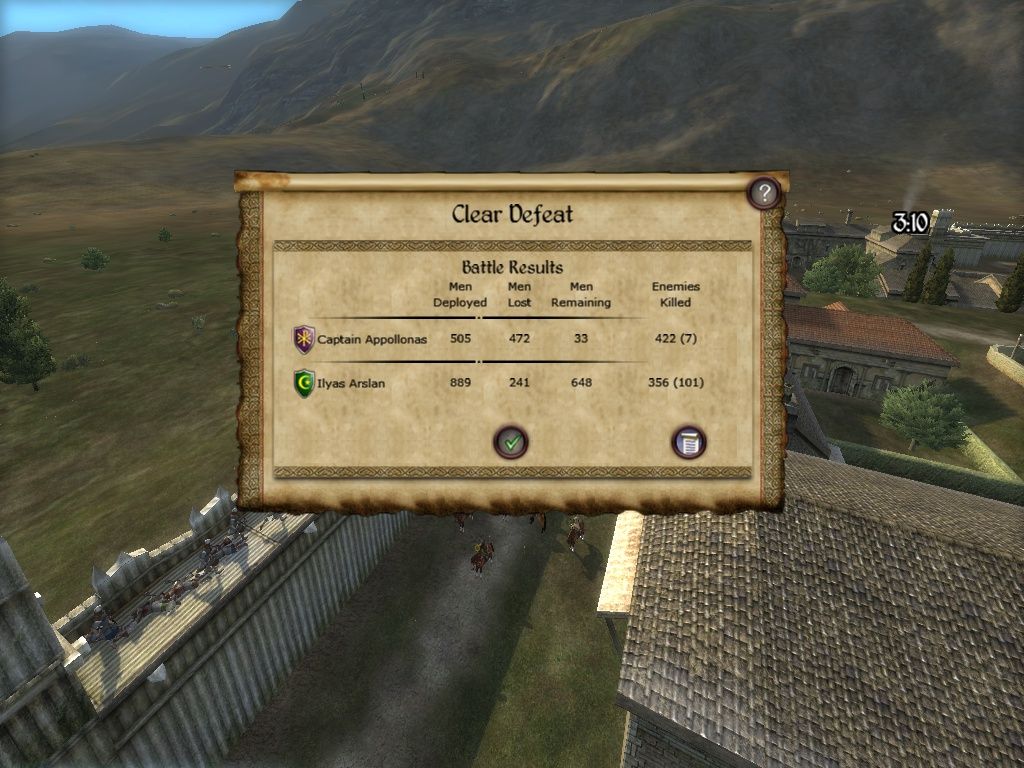

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:After Alexios' death, his firstborn daughter Anna seized the power in Constantinople, taking advantage of the absence of her brother Ioannis, busy in campaigning against the Pechenegs. With her husband Nikephoros Vriennios the Younger as Symbasileus the "Queen of Thieves", as she would have been dubbed by later historians, ruled over the Empire in one of its most turbulents periods. During her short and ill-fated reign, in fact, the thema of Karadeniz, on the Black Sea, got invaded and conquered by seljuq warlord Ilyas Arslan; in the meanwhile, Crimaea fell to Cuman invaders and the western half of the Empire got ravaged and sacked by venetian adventurier Cataldo Mocenigo, whom she had hired to prevent her brother Ioannis to seize the throne he rightfully claimed. After Mocenigo's death in the Battle of Dyrrachium at the hands of Strategos Theodosios Opsaras, her brothers Ioannis and Isaakios Komnenos finally marched against the capital and overthrew her and her husband. She died in 1153 in the monastery of Kecharitomene, leaving the Alexiad, a chronicle of the events happened during her father's reign, as her sole heritage.

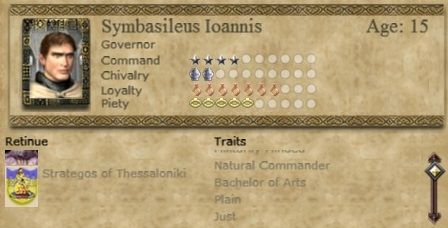

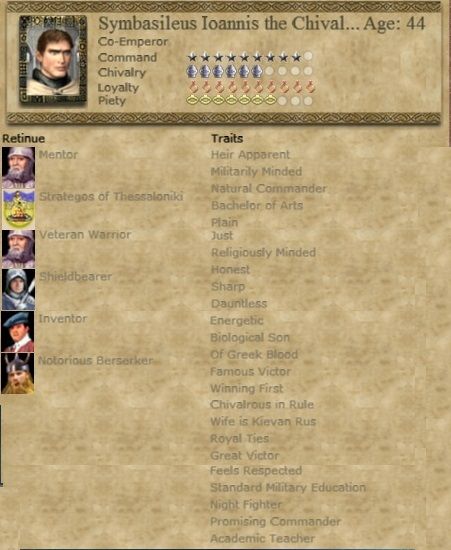

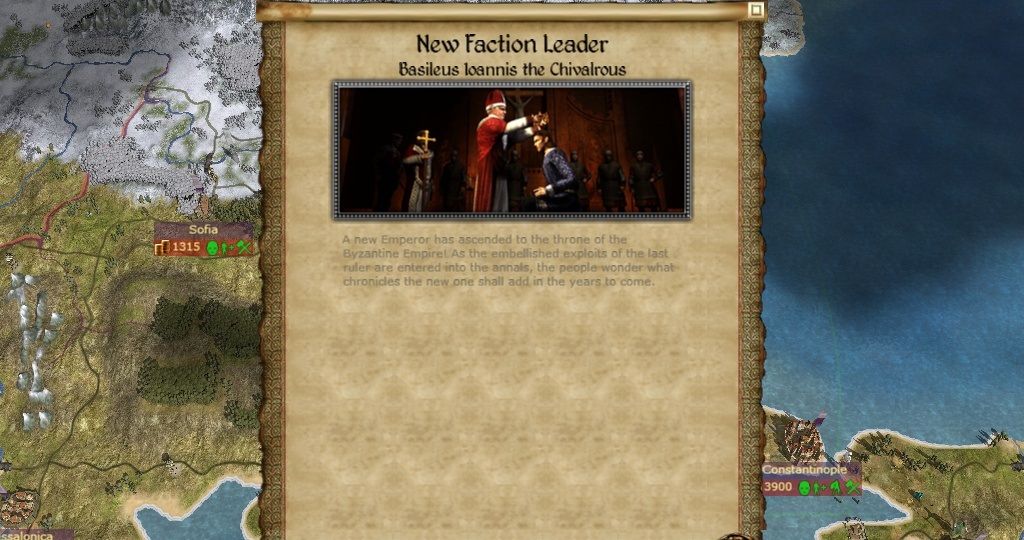

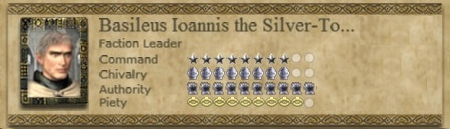

- Ioannis II the Chivalrous (1128-1153 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

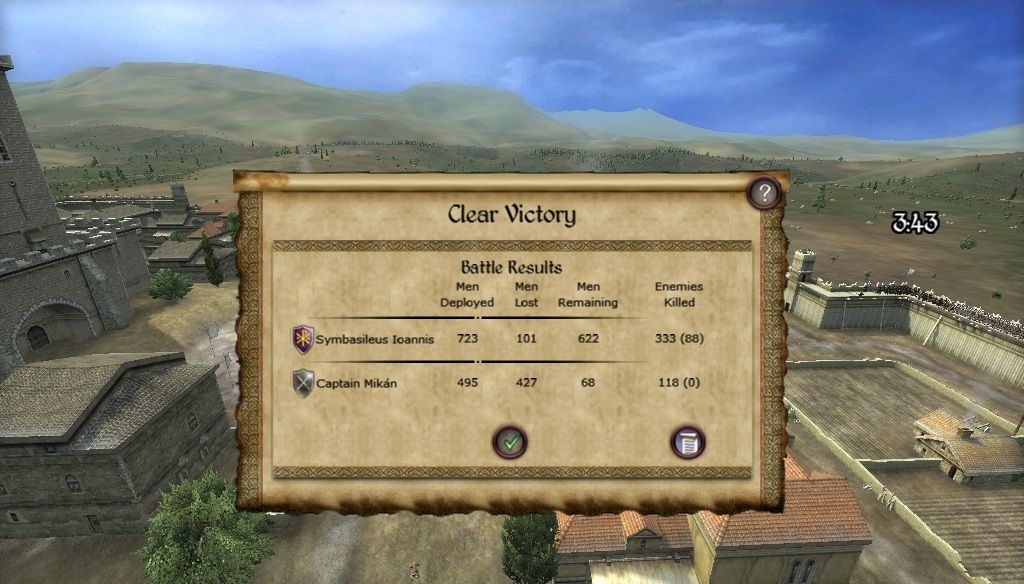

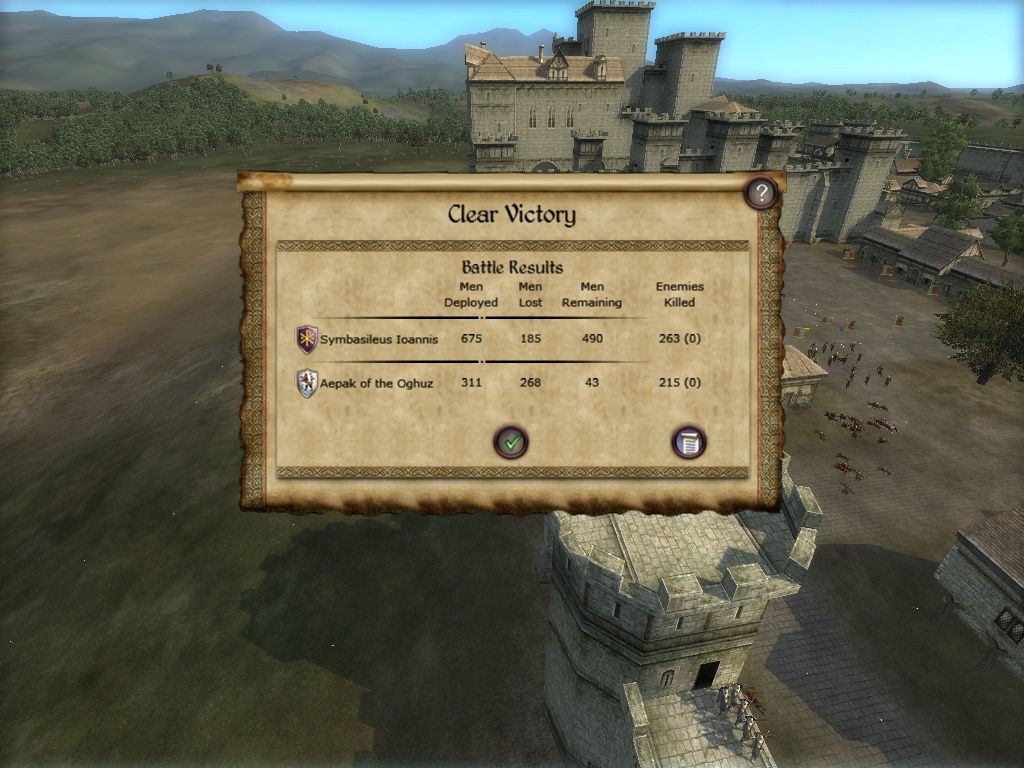

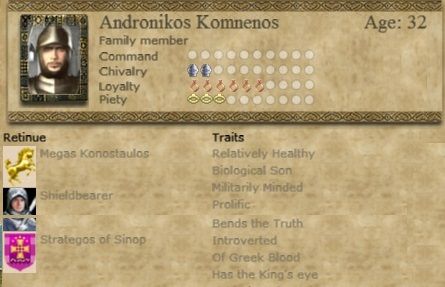

First born son of Alexios I Komnenos, Ioannis - dubbed as the Chivalrous for his magnanimity - grew an impressive reputation as a commander during his father's reign, leading the Empire's armies to victory against Bulgarians, pechenegs, crusading adventuriers and usurpers. In 1124 AD his sister Anna spoiled him of his birthrights by seizing their father's throne; four years later, Ioannis, with the help of his brother Isaakios, Strategos of Adrianopolis, marched against the capital and overthrew her and her husband. Shortly thereafter, after having promoted as Megas Logothethes his brother Isaakios, he led his armies west, defeating the Venetians at Ragusa in 1131 and the Normans, which had invaded once again the Balkans, in 1132 AD in a night battle at Durazzo. With the help of King Kalmàn I of Hungary, he then expelled the Venetians from the Balkans in 1133-1138 AD. In these campaigns, however, his second born son Nikodemos found death in battle, something which greatly shocked the Basileus, who since then showed an incomparable magnanimity which gained him nicknames such as "the Chivalrous" and "the Humane".

In 1140-1145 AD he led his armies in an anatolic campaign which would end in the acquisition of Pamphilia and the recovery of Karadeniz, while his general Iustinos Vriennios defeated a third Norman invasion of the Balkans. In 1150-1153 AD he successfully repelled a Bulgarian Uprise, personally defeating the Bulgarians in the battles of Adrianopolis and Sofia. He died shortly after the pacification of the region, leaving his son Philippikos as his successor.

- Philippikos II Komnenos (1153-1173 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Arose to the throne in 1153, shortly after his father, Ioannis the Chivalrous', death, Philippikos II gifted the Empire with an unusually long period of peace (1153-1170 AD) during which, with the help of his Megas Logothethes and uncle Isaakios Komnenos, he reorganized the army, economy, and strenghtened the Empire's alliances with Kiev, Jerusalem and Hungary through treaties and marriages. He then consolidated the Komnenoi's hold on the other Houses with similar means.

In 1170-1173, on the stream with the Third Crusade, Philippikos invaded Anatolia, defeating the seljuq Amir Ozan Gazi and restoring the thema of Galatia before dying in 1173 AD, leaving his legitimate son Heraklios and one of his bastards, Efarestos, struggling for the Crown.

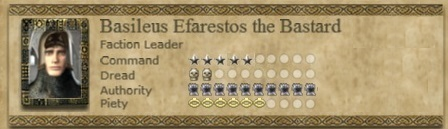

- Efarestos I the Conqueror (1173-1202 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

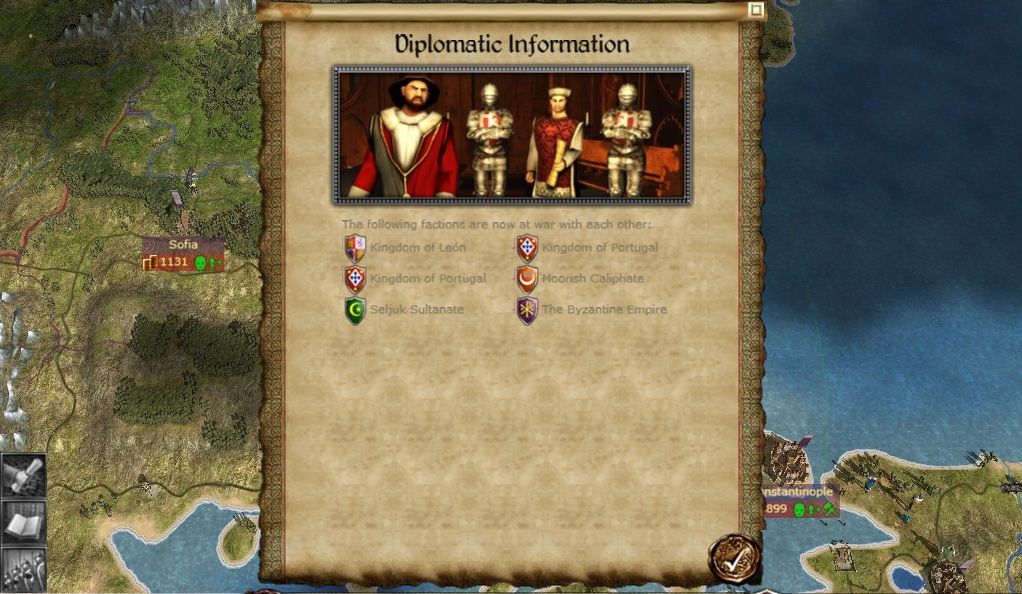

Efarestos, born as a bastard son of Basileus Philippikos II, grew among the ranks of the Army. He campaigned under his grandfather Ioannis II during the Bulgarian Uprise (1150-1153 AD) and then ruled over Bulgaria as Strategos of Sofia (1153-1173 AD), defeating several minor rebellions. In 1170-1173 AD he served in his father's anatolic campaign, successfully commanding the army during the siege of Ankara. In 1173 Ad, after their father's death, he overthrew his brother Heraklios with the support of Heraklios of House Iagaris and Kekavmenos of House Vriennios, defeating his uncle Isaakios Komnenos at Abydos; later on, he appointed Iagaris as Megas Logothethes and Kekavmenos as his Symbasileus, before leading the Empire's armies in a victorious campaign against the Seljuqs (1176-1184 AD), which ended in the conquest of Cappadocia and Cilicia, and in the expulsion of the Seljuqs from Anatolia. He then supported Vladimir and Dobrogost of Kiev against the newly crowned Hungarian King Bulcsù I, campaigning in Serbia (1191-1193 AD). Later on he forged an alliance with Heinrich VI of Germany took advantage of the Hungarian Civil War by invading Dalmatia (1195 AD). Both Serbia and Dalmatia got annexed to the Empire with the Peace of Belgrade (1201 AD), which terms provided the cession of Muntenia to Bòkoni I of Hungary in exchange for his acknowledgement of the loss of Italy to the Italian League, Kievan control over Bessarabia and German rule over Salszburg. His death of pneumonia in 1204 AD marked the beginning of a civil war among his supposed heirs.

Civil War and Interreign: the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:After Efarestos' death, the outbreak of the civil war determined the establishment of three seats of power, each one located in a different area of the Empire.

- Kekavmenos Vriennios, the Emperor in Constantinople: former Symbasileus and Megas Logothethes of the deceased Efarestos, Kekavmenos seized the throne in Constantinople, spoiling the legitimate heir, Zakarias Komnenos, of his birthrights. His authority extended, at its peak, from Serbia in the West to the easternmost fringes of the Empire in Anatolia, encompassing Constantinople and the Bosphorus. He later on lost some of his dominions to Heraklios of Adjara and Zakarias, the latter with the Partition of Adrianopolis.

- Zakarias Komnenos, the Emperor in Thessalonica: backed up by his father's veterans, prince Zakarias got acclaimed as Basileus by his troops and chose Thessalonica as his seat of power, from where he led the struggle against the usurper Kekavmenos, even managing to inflict him two field defeats, at Chrysopolis and Xanthi. In base to the terms of the Partition of Adrianopolis in 1204 AD, his authority encompassed the whole of the Aegean isles, Makedonia, Achaia, Epeiros and Albania, the Catapanate of Ragusa and the thema of Smyrna on the Anatolic coast.

- Heraklios Komnenos, Prince of Adjara and Emperor in Sinop: overthrown by his half-brother in 1173 AD, Heraklios chose to take advantage of the chaos that spreaded within the Empire after Efarestos' death by claiming the throne as his own. Backed up by the Khwarezmian Amirs of Armenia and Georgia, Heraklios, in progress of time, seized the whole of the Black Sea coast, making full use of his mighty fleet to overwhelm Kekavmenos' far weaker one. At its peak, in 1206 AD, his authority stretched from the byzantine Principality of Adjara in the East, to Nicaea and the Bosphorus in the West.

In 1206 AD Zakarias broke the ceasefire with Kekavmenos while he was busy campaigning in Anatolia against Heraklios Komnenos. His victory at Adrianopolis, Kekavmenos' death in the said battle and the surrender of Constantinopolis allowed him to launch, the following year, an anatolic campaign, which ended in the pushing back in Adjara of his uncle Heraklios, and his arise as sole ruler of the Empire, after 5 years of Civil War.

- Zakarias I Komnenos (1207-1246 AD)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Born as the only son of Efarestos I, Zakarias won his spurs serving under his father and his officers in the Balkanic War (1190-1201 AD). During the conflict, thanks to both natural gifts and training, he earned a certain reputation as a valiant commander, as shown against the Croatians at the Sava river. After the end of the conflict with Hungary and his father's death (1202 AD) civil war broke out between Zakarias, his uncle Heraklios Komnenos of Adjara and the former Symbasileus, Kekavmenos Vriennios. Through steel, treachery and diplomacy, in 1207 AD Zakarias finally managed to defeat his opponents and reunite the Empire under a sole ruler.

Shortly thereafter, in 1210 AD, broke out the series of conflicts known as the Great Jihàd, a series of muslim attacks to byzantine holdings in Anatolia. Between 1210 and 1217 AD Zakarias successfully defended Anatolia, winning relevant battles as Nigde, Lake Tun and Issus. In 1218 AD, he invaded Syria to act in support of Philip I, newly crowned King of Jerusalem, against the Fatimids' aggressions, defeating muslim prince Hamid on the Orontes. The struggle against the saracens would continue in the following years, culminating in the Basileus' victory over Shah as Salih III of Khwarezm at Trebizond, in 1223 AD., which proved fundamental to the end of so widespread hostilities.

He later on vainly tried to settle peace in the Balkans by helping Hungary, Kiev and the Holy Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of the Golden Gate, and supported Kievan Knyazich Danislav by sending in his aid his son and legitimate heir Iosif, who won a crushing defeat over the khazaro-khwarezmians on the shores of the Black Sea.

After the fall of Jerusalem and Cyprus in Fatimid hands, Zakarias campaigned in the Levant in an attempt to save the Crusader Kingdoms from downfall, relieving Acre from muslim siege and heroically defeating the saracens at Ramlah. Despite his failure in freeing Jerusalem of the saracens' yoke, his levantine campaign at least guaranteed the Franks at least a minimum of stability.After the return home, Zakarias crushed his former Megas Logothethes, Davatinos Iagaris', rebellion. He died peacefully in 1246 AD, after nearly fourty years of reign.

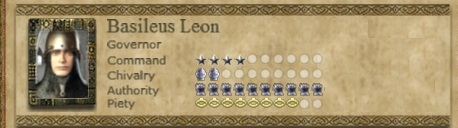

- Leo VII Komnenos (1246-1260)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Second born son of Zakarias I, Leo, whose brother Iosif died in 1235 AD, arose to the throne ten years later in virtue of the peaceful death of his father, whose military skills he inherited. Leo skillfully spent his first years of reign by securing both his throne and the Basileia's stability, with an acume often said to resemble his ancestor's, Alexios I.

In 1257 AD, after Acre and Damascus' fall in the Fatimids' hands, Leo set sail for Outremer, where he would fight to secure King Laurent's hold over the throne.

After the levantine campaign, Leo dedicated himself to the re-establishment of the Crown's authority over the dynatoi. He died in 1260 AD, fighting against usurper Lidas Vriennios in the battle of Adrianopolis, which marked the downfall of the Komnenian dinasty. He left two children, Efgenia and Arkadios.

House Vriennios (1260-still in rule)

Wealthy landowners and skilled politicians, the members of House Vriennios have tied their destiny to that of House Komnenos since the days of Alexios I's uprise, which would ultimately lead to his arise to the throne. Under Nikephoros Vriennios the Older, in fact, House Vriennios first tried to oppose Alexios' coup; later on, after a clear field defeat, House Vriennios married Alexios' cause, not only metaphorically, but through facts, too. It has in fact been through a marriage - that of Nikephoros Vriennios the Younger and Alexios' daughter, Anna - that the two Houses have put aside their quarrels, and united for the Empire's best interests. Their natural attitude to intrigue and their nearness to the highest seats of power have however aroused House Vriennios' lust for power; often, members of House Vriennios have in fact played an important role in the Empire's politics and power shifts, not always for the Empire's effective welfare. Cases worth to be mentioned would be that of Nikephoros the Younger himself, who seized the throne along with his wife Anna in the short interreign between 1124 and 1128 - with disastrous short term effects - and that of Iustinos and Kekavmenos Vriennios, whose support proved vital in the arise to power of Efarestos I, Bastard of House Komnenos. Later on, Kekavmenos fought against Efarestos' son, Zakarias, for the Imperial title, dying at Adrianopolis after a civil war known as Period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD). His nephew, Lidas, rebelled against Zakarias' son, Leo VII, in 1260 AD, defeating and killing him on his uncle's defeat's place and establishing the Vriennioi dinasty.

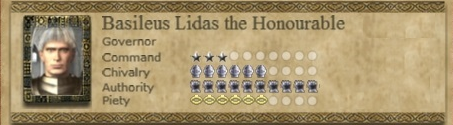

- Lidas I the Honourable (1260-still in rule)

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Fourth born and illegitimate son of Veniamin Vriennios, Lidas restlessly worked, along with his brother Theodosios, to restore the Vriennioi's former position as one of the leading Houses of the Empire. In 1248 AD he was lended by Basileus Leo VII the honorific title of Exharc, with which he wed, two years later, Kievan princess Akoulina Yaroslavich. In 1259 AD he was entrusted of the field command against Serbian usurper Christophoros Slavoupoulos, whom he defeated in battle and imprisoned. With his brother's and Slavoupoulos' help, Lidas massacred the regiments loyal to Leo VII at Belgrade and then led the army to victory over the legitimate Emperor in 1260, defeating and killing him at Adrianopolis. He subsequently took the throne, establishing the Vriennioi dinasty and fighting against Leo's partisans for control over a diminished Empire.

OTHER NOBLE HOUSES

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Noble House Vriennios

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Wealthy landowners and skilled politicians, the members of House Vriennios have tied their destiny to that of House Komnenos since the days of Alexios I's uprise, which would ultimately lead to his arise to the throne. Under Nikephoros Vriennios the Older, in fact, House Vriennios first tried to oppose Alexios' coup; later on, after a clear field defeat, House Vriennios married Alexios' cause, not only metaphorically, but through facts, too. It has in fact been through a marriage - that of Nikephoros Vriennios the Younger and Alexios' daughter, Anna - that the two Houses have put aside their quarrels, and united for the Empire's best interests. Their natural attitude to intrigue and their nearness to the highest seats of power have however aroused House Vriennios' lust for power; often, members of House Vriennios have in fact played an important role in the Empire's politics and power shifts, not always for the Empire's effective welfare. Cases worth to be mentioned would be that of Nikephoros the Younger himself, who seized the throne along with his wife Anna in the short interreign between 1124 and 1128 - with disastrous short term effects - and that of Iustinos and Kekavmenos Vriennios, whose support proved vital in the arise to power of Efarestos I, Bastard of House Komnenos.

Notable members:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:- Nikephoros Vriennios the Younger: Strategos of Adrianopolis (1100-1128 AD), later on appointed as Megas Logothethes under Alexios I (1102-1124 AD). After Alexios' death, entitled with the rank of Symbasileus during the short reign of his wife Anna I Komnena (1124-1128 AD). Overthrown by Alexios' legitimate heir, Ioannis II, Nikephors died in exile in Sinop in 1140 AD.

- Iustinos Vriennios the Silver-Tongued: son of the disgraced Nikephoros Vriennios the Younger, Iustinos brought House Vriennios to splendour once again thanks to both his brilliant military deeds, and his marriage with Basileus Ioannis II's daughter Chrysi Komnena. Under the rule of Ioannis II the Chivalrous, Iustinos brilliantly defeated a norman invasion of Epeiros (1142 AD) and was awarded with the Catapanate of Corinth. Later on, he played an important role in Ioannis' campaigns in Bulgaria (1150-1153 AD). During Philippikos II's reign he ruled over his Achaian holdings with firm hand; after Philippikos' death, he supported the Bastard of House Komnenos, Efarestos, in his victorious claim to the throne. Died in Corinth in 1196 AD.

- Kekavmenos Vriennios: son of Iustinos Vriennios. Appointed as Strategos of Athens in 1167, under Philippikos II's rule. Later on, he commanded the achaian thematas in Philippikos' victorious anatolic campaign (1170-1173 AD). After Philippikos' death, he supported the claim to the throne of his friend Efarestos Komnenos, and was later appointed as Symbasileus; with this title, he campaigned along Efarestos in his anatolic campaigns (1176-1183 AD). He then coordinated the reorganization of Anatolic thematas, arranged a marriage between his daughter Loukia and the Crusader Prince Philip de Bourq, and supported with money and mercenaries King Baldwin IV's victorious attempt to reconquer Jerusalem. After Efarestos' death, he seized the throne as his own, giving birth to the period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD). Despite the defeats suffered at Chrysopolis and Xanthi by Zakarias Komnenos, Kekavmenos saved his throne by signing the Partition of Adrianopolis, dividing Imperial authority with the Komnenian prince. Despite his brilliant deeds in his anatolic campaigns against Heraklios of Adjara in 1205-1207 AD, Kekavmenos ultimately lost the throne and his life to Zakarias in the battle of Adrianopolis (June 1206 AD). His sons were spared their lives, and later on forgiven, by Zakarias, thus allowing the Vriennios family to continue wielding its role in byzantine politics.

- Aemilianos "the Bastard": second born natural son of Kekavmenos, Aemilianos inherited his father's military prowess, and showed it during the whole of his life through his long and rich military career.

In 1194 AD, he took part in King Baldwin IV's reconquest of Jerusalem at the head of the byzantine reinforcements. Entitled as Strategos of Caesarea, during the period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD) he led the defense of Anatolia against the invasion of Heraklios Komnenos, Prince of Adjara, defeating him in the battles of Heraklea Pontica (1203 AD), and reconquering Abydos (1205 AD). In 1206 AD, after his father's death in the battle of Sofia, he led an anatolic army in Thracia in an attempt to relieve Constantinople from Zakarias Komnenos' siege, but got betrayed by his lieutenants Davatinos and Iakovos Iagaris and then brought in chains in front of the newly crowned Basileus Zakarias I. He was later on spared his life, and allowed to join once again the army's ranks, among which he fought in the battle of Nigde (1210 AD). In 1213 AD, as an award for his outstanding performance in defending Eastern Cappadocia from armenian warlords, he got reintegrated in his role as Strategos of Caesarea.

When, the following year, Tarkan Mohammed, atabeg of Mosul, rushed into Anatolia after his victory at Erzerum, Aemilianos defeated and killed him in the battle of Karaca with the help of his arch enemy Iakovos Iagaris.

From there on, he continued ruling over Cappadocia, repelling muslim infiltrations of the border and skillfully administrating his thema until his death, came in 1238 AD; six years later, his arch enemies, the Iagaris, experienced a traumatic downfall.

- Veniamin Vriennios: firstborn son and heir of Kekavmenos Vriennios. He earned a rispectable reputation as a fighter and commander during Efarestos' balkanic campaigns (1191-1201 AD), a period during which Veniamin highly highlighted himself for his skillful actions in the sieges of Pristina and Belgrade, and in several smaller campaigns for the submission of Serbia. In the aftermath of the war, he got entitled of the double Strategate of Raska and Serbia, with Belgrade as his seat.

After Efarestos' death in 1201 AD and his father, Veniamin's father, Kekavmenos', seizing to the throne led to the outbreak of the period of the Three Emperors, during which Veniamin often took the lead of his father's armies against his enemies. Between 1202 and 1205 AD, he defended Serbia from the attacks of Zakarias Komnenos' lieutenant, Apionnas Murtzuphlous, before being eventually defeated by the two in the battle of Pristina. He then fled East, where he started mustering the army his father Kekavmenos would later on command in the battle of Sofia. After his father's death at Sofia in 1206 AD, Veniamin commanded the garrison of Constantinople during Zakarias' siege to the city; on 26th August 1206, after the failure of his half-brother Aemilianos' attempts to relieve the siege, he ackowledged the defeat and lended the city to Zakarias, whom spared his life and later on forgave him. He died twelve years after, shortly after having received news upon his second-born son, Makarios Vriennios', death in the battle of Valona.

- Lidas Vriennios: fourth born, illegitimate, son of Veniamin, Lidas restlessly worked, along with his brother Theodosios, to restore the Vriennioi's former position as one of the leading Houses of the Empire. In 1248 AD he was lended by Basileus Leo VII the honorific title of Exharc, with which he wed, two years later, Kievan princess Akoulina Yaroslavich. In 1259 AD he was entrusted of the field command against Serbian usurper Christophoros Slavoupoulos, whom he defeated in battle and imprisoned. With his brother's and Slavoupoulos' help, Lidas massacred the regiments loyal to Leo VII at Belgrade and then led the army to victory over the legitimate Emperor in 1260, defeating and killing him at Adrianopolis. He subsequently took the throne, establishing the Vriennioi dinasty and fighting against Leo's partisans for control over a diminished Empire.

Noble House Iagaris

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Similarly to House Vriennios, House Iagaris has played a key role in the Komnenoi's politics since the days of Anna Komnena's interreign. During the Queen of Thieves' short and ill-fated reign, in fact, its most famous member, Heraklios Iagaris, served as Protoseacres; after the crowning of Ioannis II, Heraklios was spared his life and sent to the border thema of Isparta; later on, he earned Ioannis II's trust, becoming one of his most trusted lieutenants and turning House Iagaris in one of the pillars of the Komnenoi's claim to power.

Notable members:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

- Heraklios Iagaris: appointed as Protoseacres during Anna Komnena's interreign, he got later exiled to Isparta by Ioannis II the Chivalrous. There, he completely cleared his reputation of any stain left from his past alledgiances, and became one of the closest collaborators of Emperors such as Ioannis II, Philippikos II and Efarestos I. He got first entitled of the Strategate of Isparta in 1135-1140 AD; later on, for his brilliant military deeds, he got appointed of the Catapanate of Smyrna, which became the traditional seat of power for the head of House Iagaris. He served during Ioannis' anatolic (1140-1145 AD) and balkanic campaigns (1150-1153 AD). He then served under Philippikos' anatolic campaign (1170-1173 AD). After Philippikos' death, his support proved substantial to the arise to power of Efarestos I Komnenos, and got appointed as Megas Logothethes (1173-1196 AD). He died in 1196 AD in Costantinople, with his and his House's reputation completely cleared of any stain.

- Davatinos Iagaris: firstborn son of Heraklios Iagaris, Davatinos, entitled as Catapan of Smyrna after his father's death in 1196 AD, arose to political prominence during the period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD). During the early stages of the Civil War he and his brother Iakovos managed to achieve a certain neutrality by not picking any of the involved sides. In 1206 AD, he and his brother secretly swore alledgiance to Zakarias Komnenos, betraying Aemilianos Vriennios on the shores of Marmara and playing a key role in both the fall of the capital and Zakarias' later campaigns against his uncle Heraklios Komnenos. Entitled as Megas Logothethes shortly after the end of the war, he kept the charge until the Rape of Palaikastron (1242 AD), which he failed to put down. After having been replaced by Neophitos Tzimisces and fallen in disgrace, Davatinos joined the rebels and assumed their guide, leading them to the defeat of Pergamon. He died in 1245 AD, in Crete, murdered by local governors, embarassed by his presence on the isle.

- Tarasios Iagaris: the second born of the Iagaris brothers, Tarasios, entitled as Strategos of Achaia in 1200 AD, supported Zakarias Komnenos since the beginning of the Civil War. He got later appointed as his Megas Doux (chief admiral), and played a key role in the siege of Constantinople (1206 AD) and in the naval battle of Amasya in 1207 AD, during which he defeated Heraklios Komnenos' fleet. He would die peacefully in 1242 AD, shortly before his brother Davatinos arose against the throne.

- Iakovos Iagaris: third and last born son of Heraklios Iagaris, he supported his brother Davatinos' choices during the Civil War, playing a key role in their coup against Aemilianos Vriennios in 1206 AD. With his brother entitlement as Megas Logothethes, he inherited the governorship of the Catapanate of Smyrna. In 1214 AD, along with his arch enemy Aemilianos Vriennios, he defeated and killed Tarkan Mohammed, atabeg of Mosul, in the battle of Karaca. After the battle, he returned to his seat of power, Smyrna, where he reigned peacefully until the Dynatoi Crysis of 1242-1244 AD, when Davatinos arose against Zakarias I. After his brother's defeat at Pergamon and succeeding death in Crete, Iakovos was exiled to Norway, where he wed King Sigurd's daughter Ingrid and fathered a new line of Iagaris, Kings of Norway.

Noble House Kantakouzenos

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Its prestige often shadowed by that of the other Houses throughout the XIIth Century, House Kantakouzenos slowly grew in importance during the period of the Three Emperors and the following conflicts with the Empire's islamic neighbous, before finally arosing to a position of prominence in 1221, with Theodoros Kantakouzenos' marriage to Ioulia Komnena, daughter of former Basileus Zakarias I Komnenos.

Notable members:

- Theodoros Kantakouzenos: firstborn son of Basil Kantakouzenos, Theodoros, entitled as Strategos of Adana in 1210, distinguished himself in occasion of Cahid Ersoy's invasion of Cilicia, in 1213 AD, which he brilliantly repelled in the battle of the Cilician Gates. Two years later, he fought at Issus among the ranks of Zakarias I Komnenos' army, as a senior member of the Basileus' military staff.

In 1219, his stubborn resistance slowed down the invading muslim host of Yasin Sivasi and Kursad Erbili to the point of allowing Zakarias to halt their advance and defeat them in the battle of Adana. His brilliant behaviour, and the reputation he enjoyed among the anatolic strategoi, earned him the Basileus' favour, the hand of his daughter, Ioulia Komnena, which he wed in 1221 AD, and the title of Protoseacres.He continued wielding a considerable power in the following years, supporting Zakarias during Davatinos Iagaris' uprise, and keeping the Strategate of Cilicia until his death, came in 1258 AD.

- Markianos Kantakouzenos: only child of Theodoros Kantakouzenos, Markianos grew up as a close friend of Basileus Leo VII, who lended him the thema of Cilicia after Theodoros' death in 1258 AD. After Leo VII's death at Adrianopolis, and Lidas' usurpation, Markianos fought beside Konstantinos Anargyros to restore the Komnenoi to the throne.

Noble House Machonios - Tzimisces

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Proud and glorious, House Tzimisces boasts a lineage which traces back to some of the finest generals the Empire has ever produced. Among the most prominent exponents of the Tzimisces, is Ioannis I Tzimisces, one of the best byzantine generals of the XIth Century, arose to the throne with the betrayal of Nikephoros II and the following marriage to his widow, Empress Theophano. After Ioannis' death of tiphus during a campaign in the Levant, House Tzimisces' power slowly began to fade, even though recent events can be seen as a restoration of her former prestige. Through the marriage with the anatolic family of the Machonioi, the Tzimisces are now once again major players in byzantine politics.

Notable members:

- Neophitos Tzimisces: only child of Gavriel Tzimisces, Neophitos inherited from his father a substantial fortune, which he took advantage of to regain his House's former prestige and power. Thanks to his renowned administrative and military skills, Neophitos was entitled by Zakarias I as Megas Logothethes after the dismissing of Davatinos Iagaris, against whom he later on fought beside Zakarias' son, Leo. With Zakarias' death in 1246 AD and Leo's arise to the throne, Neophitos was formerly dismissed as Megas Logothethes, something he took revenge of fourteen years later, when, after Leo's death at Adrianopolis, he helped, along with his son-in-law Phokas Machonios, Lidas I Vriennios to seize the throne. This earned him his re-establishment as Megas Logothethes.

- Phokas Machonios - Tzimisces: head of an important Cappadocian family, in 1250 AD he wed Neophitos Tzimisces' daughter, Vasilia, thus uniting House Machonios to the prestigious Tzimisces family. When Lidas killed Leo VII at Adrianopolis, Phokas, Merarches of the Tagmatas, turned to his side and helped him in seizing the city.

Noble House Anargyros

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

House Anargyros originated as a collateral branch of the powerful Argyros family, and arose to a position of preminence among the pontic dynatoi during Zakarias I's reign. Under his son, Leo VII's, rule, the House entered the political scene in Constantinople through the entitlement, on Leo's behalf, of Konstantinos Anargyros as Megas Domestikos. From there on, House Anargyros would be one of the die hard supporters of the Komnenian dinasty.

Notable members:

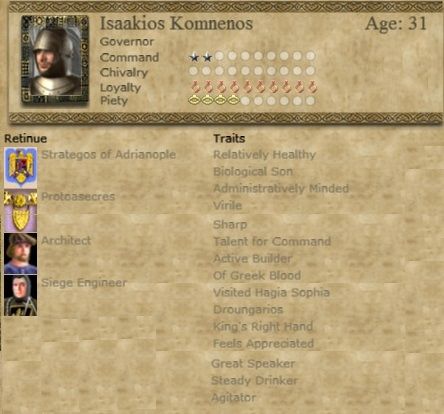

- Konstantinos Anargyros: son of a minor pontic noble, Konstantinos, Strategos of Sinop, served among the army's ranks beside young Leo Komnenos and Markianos Kantakouzenos, both of whom he befriended. After Leo's arise to the throne, Konstantinos emerged on the byzantine political scene in virtue of his skills and loyalty, which earned him, in 1248 AD, the title of Megas Domestikos, commander of the army. When, after Leos death in the battle of Adrianopolis and Lidas Vriennios' accession to the throne, Konstantinos rallied his forces to fight for thei Komnenoi heirs' rights from his new see of Cyprus.

Noble House Erotikos

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Despite their close ties to the Komnenians - being the Komnenoi's forefather, Manuel Erotikos Komnenos, an exponent of their House - the Erotikoi, throughout much of the Komnenian Era, never played an important role in byzantine politics, wielding, at the most, a tenuous authority over the Bulgarian families. The House finally emerged on the byzantine political scene with the entitlement of Marianos Erotikos, on behalf of Basileus Leo VII Komnenos, as Strategos of Bulgaria.

Notable members:

- Marianos Erotikos: entitled as Strategos of Bulgaria in 1247 AD, Marianos cunningly took advantage of later events to increase his House and his own power. During Lidas Vriennios' rebellion in 1260 AD, Erotikos' ambiguous and treacherous behaviour proved fundamental in the rebel's victory at Adrianopolis, and subsequent seizing of power.

MINOR NOBLES

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Theodosios Opsaras:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

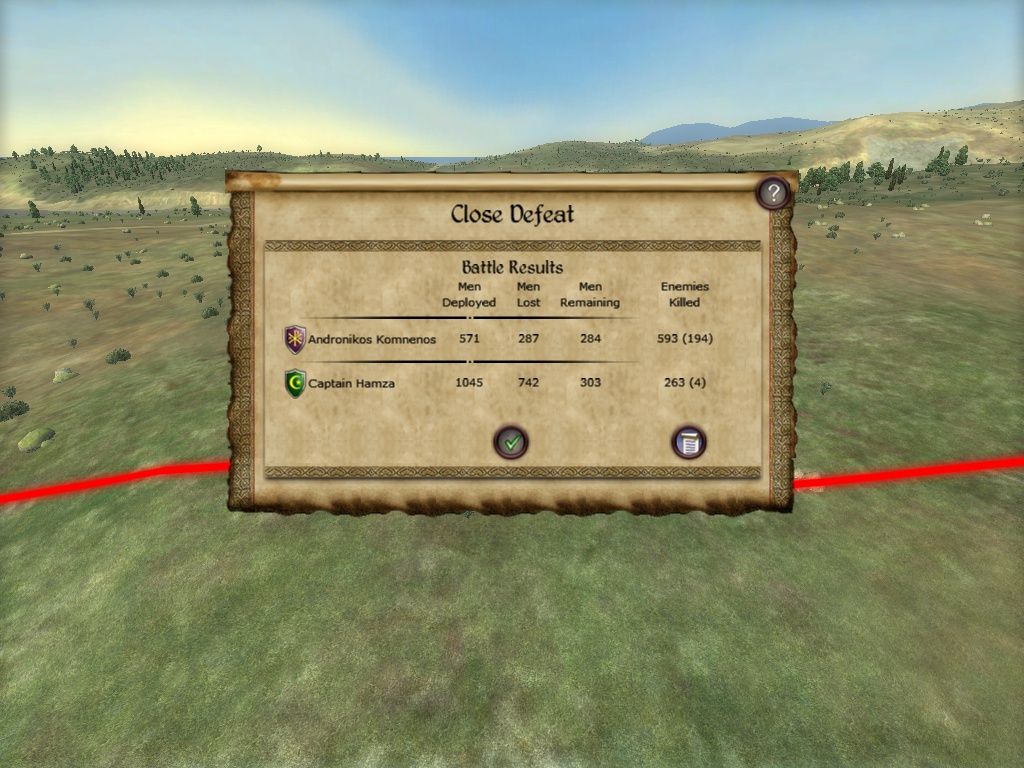

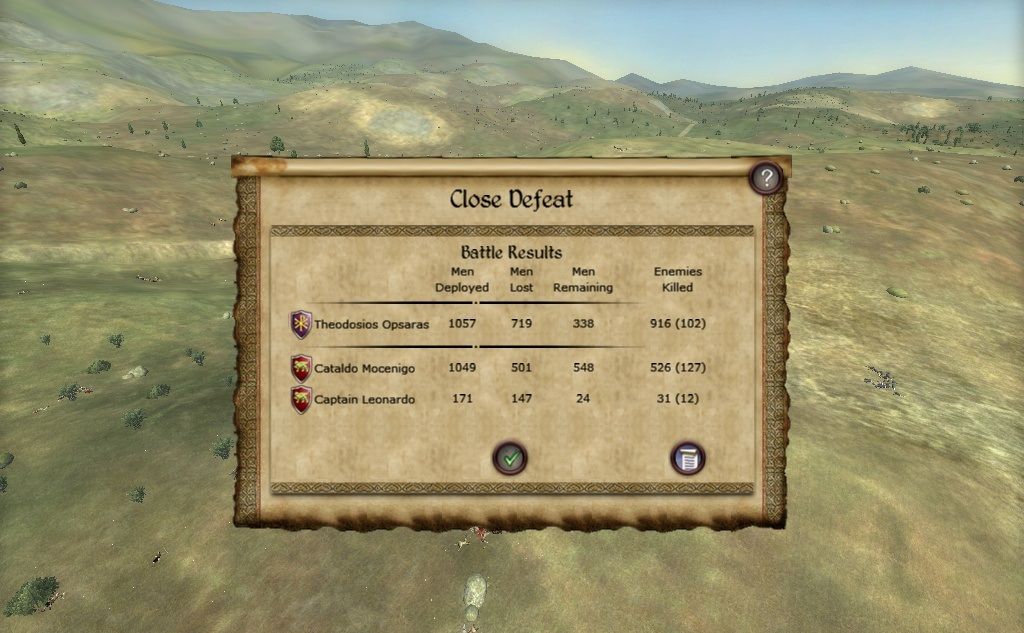

Stubborn supporter of the Komnenoi, Theodosios got entitled of the Strategate of Achaia in 1103 AD, during Alexios I's reign, a role in which he supported and joined to Ioannis Komnenos' successful reannexation of Epeiros. Along with Ioannis, he defeated in 1112 AD Gavras' uprise against Alexios I's rule. With the death of Alexios I in 1124 AD and the usurpation of Anna Komnena and her husband Nikephoros Vriennios, Theodosios supported Ioannis in his claim to the throne, coordinating the defense of Western Greece and Epeiros against Cataldo Mocenigo's raids. Despite Cataldo's death during it, the battle of Durazzo ended up as a clear defeat for Theodosios, who got forced to whitdraw to the paeninsula of Dyrrachium. There he achieved an heroic victory against Mocenigo's lieutenant, Leonardo Alberighi, before dying as a conseguence for the wounds suffered in battle. His actions proved fundamental in Ioannis II's victory in the Civil War, and crowning in 1128 AD.

Kalamodios Imerios:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Entitled as Strategos of Trebizond by Heraklios Komnenos, Prince of Adjara, Imerios supported his claim to the throne during the Period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD). As Heraklios' lieutenant, Kalamodios earned several victories against the Vriennoi forces, before being defeated in the battle of Kastamonu. After the end of the Civil War he reigned as Strategos of Trebizond, until Tarkan Mohammed's invasion of Anatolia, during which he was defeated and killed in the battle of Erzerum (1214 AD).

Apionnas Murtzuphlous:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Arose to the rank of Merarches of the Scholarii during Efarestos I's reign, Murtzuphlous fought beside him in his balkanic campaigns (1191-1201 AD), highlighting himself in the sieges of Pristina and Belgrade. After Efarestos I's death, Murtzuphlous, now entitled as Catapan of Ragusa, supported Efarestos' only son, Zakarias, during the Period of the Three Emperors (1202-1207 AD), arising to the rank of his Megas Domestikos.

In this role he led the defense against the invading muslim forces of Ayshun al-Andalusi, defeated in the battle of Valona. He died peacefully in 1247 ADSpoiler Alert, click show to read:.

Ioasaph Kallergis

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:Son of a lesser comes, the skilled Ioasaph soon earned the attention of Basileus Leo VII Komnenos, who entitled him as Megas Logothethes after Neophitos Tzimisces' dismission. In this role, he collaborated with Leo in his attempt to diminish the dynatoi's power, which provoked Lidas Vriennios' uprise.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote