| Modern recreation of the Star of the Righteous Many, also the standard of their Sept of Esoph ('Illami) |  |

The third and smallest of the three notable Mun'umati nations to emerge from the Riverlander Dark Age were the 'Illamites, or 'Illami - the 'Righteous Many', in their own tongue. Despite their relative weakness compared to the Shamshi and Taibani, as well as their location in the fairly remote northern reaches of the old Zaba-Tutuli Empire, they are actually the best known of the three, on account of having recorded their history in their religious scriptures: the Qabal hith el-'Ilm, or 'Teachings of the Righteous'. While obviously the 'Illamites' retelling of their history is heavily influenced by their teachings, and there are more than a few parts which modern historians believeto be either exaggerated or outright impossible, the fact remains that the Righteous Many left behind a far more complete picture of what they went through during the dark age of 10,015-10,500 AA than either the Shamshi or Taibani did, and in fact a fair amount of what is known of those other two Mun'umati tribes was derived from what the 'Illamites wrote of them in their scriptures.

According to the Qabal, the 'Illami people got their start with the patriarchal figure Hizzar bet-Haimon, a shepherd with seven sons who heard the voice of the Lord Above (their god) while tending to his flock one night. The Lord Above informed Hizzar that, on account of his simple but virtuous character and lifestyle, he had been chosen to father a nation of 'the righteous many' ('Illami) whom said Lord wished to inherit a promised land & turn it into a paradise on Earth. At the urging of their God, Hizzar and all his kin left their oasis town in the southern Great Sand Sea and began the arduous trek to this promised land, which is referred to as the Heshlema (simply, 'our land', though it was also called the Lem hith el-'Illam or 'land of the righteous' by the 'Illamites themselves after they settled on it), following the North Star which the Lord had proclaimed to be their guide. However, Hizzar died long before they left the Great Sand Sea, passing naturally in his bed at the age of ninety-six (after thirty years of travel, by which point he was called Bel-Hizzar or 'Lord Hizzar'), and it fell to his sons and grandsons to lead the migration which, by this point, had been swelled as more and more Mun'umati joined the growing 'Illamite tribe. Those seven sons of his would thus become the progenitors of the seven clans or 'Septs' - more accurately, castes - of 'Illamite society.

| A woodcut illustration of the Lord Above directing Hizzar to follow the North Star |  |

However, the 'Illami would not complete their journey in those seven sons' lifetimes, nor in the lifetimes of the next few generations that succeeded them. According to the Qabal, 'six-and-sixty years' after Bel-Hizzar's passing they were surprised and enslaved by the 'Awali at the western edges of the Great Sand Sea, still a ways away from their final destination. For two thousand years, the 'Illami had to labor as slaves beneath the yoke of the 'Awali, who are referred to as the 'river heathens' in the Qabal and were condemned for their cruelty and tendency to draft 'Illami men for their endless wars, while also taking their daughters for the Paramount King's harem. (Zaba-Tutuli records indicate the enslavement of an 'Ilali' tribe around 8200 AA and the 'Awali were not known to be particularly gentle taskmasters in general, so this part may well actually be completely true)

Around 9,900 AA, the prophet Emel bet-Emek reportedly proclaimed that 'soon' two great hordes from the East would descend upon the river-heathens and lay them low; razing their great cities to the ground, butchering their armies and carrying their own women and children, from the elaborately dressed wives of the princes to humble crofters' women and daughters, away in chains, as the punishment the Lord Above had prepared for that prideful and tyrannical lot. While Emel was promptly executed for his preaching, it turned out that his prophecy was only off by a hundred years. When the rest of the Mun'umati assailed Zaba-Tutul's borders just a little over a century after Emel's death, the 'Illami instantly and unanimously rebelled to support the invaders under the leadership of Yuvel bet-Esef, who the 'Illami venerated as their 'First Prophet', and bravely fought on the side of their erstwhile liberators through both defeats and victories.

According to the Qabal, the famed Yuvel was born to the priestly caste, though his family was annihilated in a periodic 'Awali purge of the 'Illamites' elite following a rebellion in his infancy, and he was then adopted & raised as a son by the infertile 'Awali princess Balitani: a niece of the 'Awali Paramount King, Muš-eni-bal, whose marriage had produced no children. Upon his sixteenth birthday, Yuvel flew into a fury upon witnessing the savage beating an 'Awali taskmaster was meting out to a pair of slaves (little did he know, they were his cousins), forcing him to flee into the eastern sands. There, he lived for ten years and married the Shamshi lady Idriya, a daughter of the mighty Luminous King Harith bar Hassur. However, upon being saved from heatstroke after getting lost in the desert by the Lord Above and informed of his true heritage, Yuvel returned to 'Awali lands just ahead of the Mun'umati invasion to organize a rebellion among his compatriots, and secured the support of all seven of the great Sept elders after impressing them with miracles that included making fresh water flow from a rock, turning his staff into a serpent and then back again, and feeding a throng of starving 'Illami with but four loaves of bread. In a tale considered to be of even more dubious historicity by modern scholars, he also personally appealed to Muš-eni-bal to let his people go in exchange for being spared from Emel's prophesied horde, only to be repeatedly spurned by the man he once looked up to as an uncle; accordingly, the Lord Above afflicted the 'Awali with nine great disasters in preparation for the tenth and greatest of them all, the Mun'umati invasion itself.

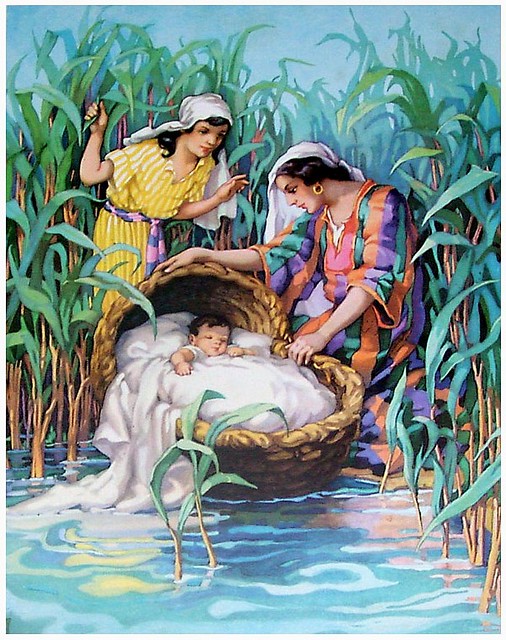

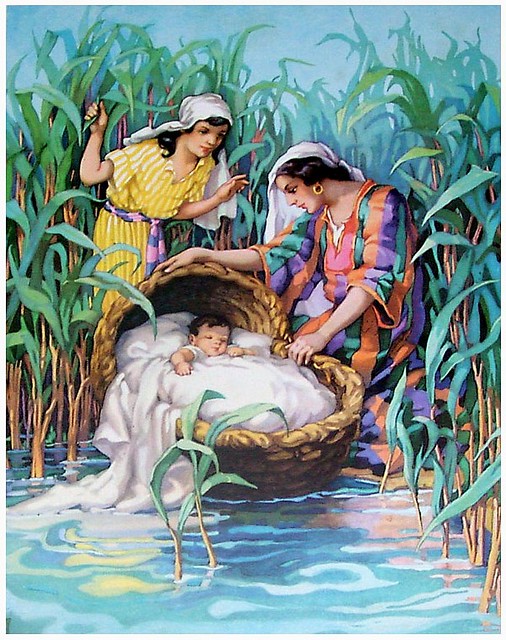

| Artist's imagining of Balitani's discovery of the infant Yuvel, c. 9,980 AA |  |

Yuvel's background in the royal court of Zaba-Tutul and princely education, no doubt including martial pursuits, gave him an insight into how the 'Awali war machine worked, and he was able to lead his people to victory over their foe time and time again as a result. After the eventual Mun'umati victory and the destruction of Zaba-Tutul, he was universally acclaimed the first Steward of the Lord Above on Earth (or simply 'Samerah', 'steward') by the 'Illami - essentially, their first recognized supreme leader since Bel-Hizzar, superseding the council of seven great elders who had governed them between Bel-Hizzar's death and the defeat of Zaba-Tutul - and following the disintegration of the Shamshi-Taibani alliance, he went on to lead them to Heshlema with no further molestation, using the North Star as their guide just as their ancestors did. Unfortunately, once the Righteous Many arrived at their land of milk and honey at the mouth of the great River Hasbana, they found that there were still 'Awali colonies and pre-'Awali native tribes living there; no doubt, they would have to be expelled, assimilated or exterminated if the Righteous Many were to have any chance of converting the region into Heaven on Earth...

| Artist's illustration of Yuvel directing the 'Illami to cross the Hasbana, c. 10,020 AA |  |

Which was, of course, exactly what they did. An entire book of the Qabal, the First Book of Stewards, records the wars waged by the 'Illami against the natives of their new neighborhood over an approximately 500-year period (the same length of time it took for the Shamshi to pull themselves out of the dark age they helped inflict on the Riverlands), and frequently describes war crimes following their victories (which, to be fair to the 'Illami, were not exactly exceptional for the time period) in manners as clinical and laconic as 'and upon achieving their victory, the Righteous Many cleansed these lands of (X)' or 'and when the Lord Above had delivered (Y) into their hands, the Righteous slew all the men they could find and took the women and children away in chains'. A few persistent foes did emerge to trouble the 'Illami over the course of many Qabali verse and chapters; chief among them were a pocket of surviving 'Awali towns, led by the city of 'Umm midway up the Hasbana, and the Enezi, a rival Mun'umati tribe that lived in the marshes southeast of 'Illam. Unlike the 'Awali and to a lesser extent the Shamshi, the 'Illami actually recorded their defeats, though they almost always ascribed losses in battle to not being sufficiently faithful to their Lord Above.

Throughout these wars, they were led by Yuvel and more Stewards after him, including seven more notable 'Great Stewards' - Simcha bet-Tomer, Shachar bet-Yanev, Anat bet-Chabed, Pabel-zeg bet-'Aim, Zalalel bet-Jachin, Atarah bil-Melelem (the only woman among the Great Stewards) and Galad bet-Lior - who were mentioned in more than one chapter of the Qabal, and at least thirty-six 'lesser' Stewards who were mentioned only once or twice each. None of these Stewards inherited their position: rather, they appear to have been elected by a general assembly of the Septs' free men and then blessed by the chief priests of the 'Ilmi, the foremost of the seven tribes of 'Illam. (or, as the Qabal would say, they were 'chosen by the Lord Above and anointed by his foremost servants on the Earth', presumably meaning that the Lord worked through the Septs' voters) The 'Illami do not appear to have used the title of 'king', believing that the only King of the Earth and indeed all creation was the Lord Above, and that their leaders were at best Stewards appointed by Him to...well, steward His chosen people.

| The Steward Zalalel bet-Jachin has two followers hold his hands up in prayer while his men battle the Enezi (the 'Illami win as a result), c. 10,377 AA |  |

The Illamites are thought to have emerged from their own murky dark age with the ascension of the first hereditary Steward around 10,500 AA: Elech bet-Eyal, a mighty warlord born to the Sept of Rechab. According to the Qabal, when Elech was still a young child his father Eyal took a mortal blow for the Steward Galad bet-Lior in a battle with the Enezi (a rival Mun'umatic tribe), and to repay his debt Galad took Elech into his own household. There, he became fast friends with Galad's son Lior (mentioned to have been a boy of the same age) and proved to excel at his martial training - no other young aspiring warrior in the Steward's household, young Lior bet-Galad included, could shoot faster or more accurately than him, ride faster than him, throw a javelin further or with more precision than him, or defeat him in sparring sessions with spear, sword, ax or club. When Elech and Lior were sixteen, Galad took them with him to the great Battle of the Vale of Haz'rath against the Shamshi, whose host reportedly outnumbered the 'Illami five to one and included a Golga mercenary called Gulg by his foes. Gulg taunted the 'Illami, daring any man brave enough among their ranks to come forth and meet him in single combat, and even lifted his loincloth to flash them. Though they must have been burning with shame, not one of the 'Illamite soldiers and officers, not even Galad himself, stepped forth - until Elech did.

What happened next was a duel that would enter the realm of legend. At the prospect of fighting an untested warrior, still half a boy, Gulg laughed and told Elech to run home to his mother. Yet Elech persisted, and after he proclaimed that the Lord Above would deliver Gulg's head into his hands, the giant became sufficiently irate to charge at him, iron-headed spear raised high to turn the lad into a bloody smear. Elech stuck three javelins into the earth before him, and threw them one by one at Gulg; the first went too high & grazed the titan's helmet, the second fell too low & barely slowed him down after impacting against his vest of bronze scales, and the third struck the Golga in the eye & sank all the way into his brain. Gulg took one quick step, then a slower one, and finally skidded to a halt (carried forth by the momentum of his charge) before collapsing at Elech's feet. Upon witnessing Elech drawing his downed opponent's great sword, decapitating him with it and then raising the head up in his hands, the 'Illami cheered to the skies and proceeded to defeat the demoralized Shamshi, routing them 'with as much ease as their champion had had in slaying that of the heathen enemy' according to the First Book of Stewards.

| Elech prepares to strike off the fallen Gulg's head while the Shamshi flee in terror, c. 10,495 AA |  |

At a feast held after the battle, the overjoyed Galad proclaimed Elech his foremost champion and promised him the hand of his eldest daughter, Herut. But this lady was described as plain-looking and five years older than Elech, who in turn had already found himself a love-match in the lowly but beautiful Fayna bil-Ilan, the daughter of a farmer whose homestead he'd passed through with the rest of the 'Illami army on the way to the Vale of Haz'rath - the second-lowest of the seven Septs of Illamite society. While Elech could not refuse Galad publicly, that night he and Fayna eloped, humiliating and outraging their overlord. Galad sent his soldiers to scour the land for the two runaways and bring back their heads, but Lior defied his father and worked to allow Elech and his chosen wife to flee the Steward's wrath for the 'land of Itai', now understood by modern scholars to have been a general term that referred to lands beyond 'Illam's northern borders.

Three years later, a Shamshi-Enezi alliance invaded 'Illam and crushed Galad's army at the Battle of Benyas, where the Steward was killed and Lior captured. In the confused political situation that followed, Galad's cousin Meit bet-Rotem seized power with the support of his wife Basya bil-Efir (actually his much younger second wife, his first wife and the mother of Herut & Lior having been mentioned as passing away from an illness several verses earlier) and chief scribe Eiran bet-Doron, whose brother in turn was the most senior surviving captain in the 'Illami army. This triumvirate made an unfavorable peace with the Shamshi and Enezi, making significant land cessions and promising to pay a tribute of 1,000 cattle and 2,000 bales of wheat every year; and, cursing the Lord Above for not aiding 'Illam and granting them victory, turned their backs on him. Instead, Meit crowned himself 'King of 'Illam' and married Basya, and ordered the veneration of all three of them as 'Illam's new flesh-and-blood gods.

| Lior bet-Galad gives Elech his sword as he advises him to flee |  |

Neither Meit's proclamation of godhood nor his surrender were accepted by most of 'Illami society, and within a year Elech and Fayna returned to find their homeland ablaze in a vicious civil war between the triumvirs (now backed by the Shamshi army) and numerous, but disorganized and leaderless, conservative rebels. Elech naturally aligned himself with the latter and, upon proclaiming that he would restore the old faith and ways, was named a 'man after the Lord's own heart' by High Priest Meshul'el bet-Keshor and unanimously acclaimed Steward by the insurgents...on the condition that he take Herut as his second wife, thereby unifying the most conservative elements of the rebellion with those from the lower Septs. He defeated Meit's armies and his Shamshi allies time and time again, while the triumvirs were wracked by internal divisions; Basya seduced Eiran's brother into assassinating him after she came to suspect he was planning to order her own death, and was later herself strangled by Meit after trying to poison him at supper without taking into account the likelihood that he'd have a food-taster on hand.

Alone and abandoned by virtually all of his followers, the increasingly unstable Meit fled 'Illamite lands around 10,499 AA and returned at the head of a Shamshi army before Elech could consolidate his rule, but was defeated and slain in the Battle of Pinchon on the 'Illami-Shamshi border; according to the Qabal, when the battle was lost he dressed himself in woman's clothing and attempted to flee, having garbed one of his slain bodyguards in his own ostentatious armor, but was run down and killed by Elech himself. As part of the peace terms, the Shamshi had to return all of the land Meit ceded to them and release Lior, while the tribute the 'Illami owed them was reduced by half (and, within a year, went unpaid). Thus did Elech emerge as the undisputed ruler of the 'Illami, and his founding of their first permanent capital at the mouth of the Hasbana - which he named Sa-Bel, 'seat of the Lord', in honor of his people's divine patron - marks the end of the Riverlander Dark Age north of Shamshi territories.

| Steward Elech enters his new capital of Sa-Bel in triumph, c. 10,500 AA |  |

| The early 'Illamite language | The language of the 'Illami belonged to the broader Mun'umati language family, but shows markedly less 'Awali influence than Shamshi. Instead, it appears to be more heavily influenced by their Mun'umati rivals the Enezi as well as non-'Awali natives of the land around the River Hasbana, well north of the traditional 'Awali homelands: after all, it marked the northernmost reaches of 'Awali power and was settled by relatively few 'Awali from their homeland between the Abanarir & Muryurir Rivers further south.

| Modern speech | Proto-Mun'umati | Early 'Illami | | Man, men | Mat, umati | Bat, bat'i | | Woman, women | Nisa, ranisa |

Bil, bil'isa | | Fire | Saťaš | Sethas | | Water | Ha'mul | Hem'el | | Virtue | Mayit | Me'et | |

| 'Illami society | The society of the early 'Illamites can be best described as a theocratic caste system. While officially led by a Steward elected by an assembly of all free men of each of its seven Septs to rule for life, these Stewards mostly served as war-leaders, and internal affairs were largely handled by the first of the Septs: one comprised entirely of priests and their families, who were also judges and jurists capable of initiating proceedings to depose Stewards who displeased them & outlawing members of the community for any crime. It was governed by the Twelve Commandments handed to Yuvel by the Lord Above in the last chapter of the Qabal's Book of Flight, upon which all other 'Illami laws were based, indicating that they were indeed as puritanical as a society as their Shamshi and Enezi adversaries described them:

Originally Posted by The Twelve Commandments of the Lord Above

1. Thou shalt have no lord but Me, the Lord Above, and no king save I, the King of All Creation.

2. Thou shalt invoke My Name only in praise or prayer, never in vain.

3. Thou shalt keep the seventh day of the week holy, by performing no labor and consuming no alcohol.

4. As thou honor Me, the father of all Creation, so too should thou honor thine own father and mother.

5. Thou shalt not murder.

6. Thou shalt not engage in sexual relations outside of the bounds of lawful matrimony.

7. Thou shalt not covet anything that belongs to thine neighbor, nor want more than what is thine fair share and which thou need'st to live.

8. Thou shalt not utter deceit, but serve My Truth with all thine strength.

9. Thou shalt not shy away from work in the name of the Lord Above.

10. Thou shalt not overindulge thine appetites.

11. Thou shalt not oppress those weaker than thee among the faithful, but defend them from the depredations of the unjust mighty.

12. If thou should breach any of the above Commandments, thou shalt sincerely confess and repent for thine sins with the utmost haste.

As mentioned above, these Commandments were then used as the foundation of 'Illami jurisprudence. Any free man of 'Illam who had been charged with a crime was supposed to be guaranteed a trial before a jury of their peers (specifically, seven randomly chosen men, one from each of the 'Illami Septs) that was presided over by an ordained priest, with the jurors deciding his guilt or innocence and the presiding priest then issuing his sentence based on said jury's verdict. Curiously, the 'Illami legal system operated on a presumption of innocence even in this dark age. The extra-Commandment laws and some recorded cases (likely for the purposes of demonstrating how these laws worked in practice), stretching from the time of Yuvel to the days of Anat, were compiled in the Book of Commands, some examples being:

| Excerpts from the Book of Commands |

Originally Posted by Book of Commands, 10:15-21, 11:1-9

Be careful to obey these commands I am issuing unto you, which I do at the command of the Lord Above in turn, so that you might please Him and do nothing but good in His sight.

The Lord Above will deliver into your hands the faithless nations that occupy Hashlema. But when He has done this,

you must be certain not to be ensnared by so much as inquiring after their false gods, nor their foreign customs.

You must not turn to their gods, which have no power and have failed them, nor revere the Lord Above in their ways, which are despicable in His eyes, but instead raze their temples and destroy their idols when you see them.

Those among the Righteous who do turn to the false gods of foreigners are apostates, and must die.

This, above everything else I am about to command of you, you must be diligent in observing.

If a prophet or warlock appears among the Righteous, and promises signs and miracles,

and if the sign or miracle takes place, yet the conjurer ascribes his works to a god other than the Lord Above, and encourages you to follow that god of his,

you must turn a deaf ear to his words, for he in truth serves the Lord Below in one of his many masks, as do all heathens.

It is the Lord Above whom you should solely serve. Keep His commands and listen only to His words.

The prophet or warlock must be put to death for trying to incite rebellion against the Lord who freed your ancestors in your heart, and for trying to lead the Righteous away from the narrow path which He has set for them.

If your brother, your wife, or your son or daughter secretly entices you to embrace a false god,

do not heed them, express pity or understanding for them, spare them or shield them from your wrath and the wrath of the Lord Above.

They must die, and your hand must be the first in putting them to death.

Let all the Righteous know what you have done, so that they may be filled with fear and wonderment at your zeal which pleases the Lord Above, and so that no other will ever attempt such a thing again.

Originally Posted by Commands 11:8-10

If one among the Righteous steals something belonging to another, he must be punished.

He who has stolen for the first time shall pay with his good hand;

he who has stolen for the second time shall pay with his life.

Originally Posted by Commands 12:25-29

If one among the Righteous is found guilty of maiming or slaying another, what he has done must be done unto him in turn.

If he has struck a blinding blow, he must be blinded;

if he has amputated a hand or foot, he must lose a hand or foot of his own;

if he broke a bone, the same bone within him must be broken;

and if he killed his fellow Faithful, so too must he die.

Originally Posted by Commands 12:35-36

If one who professes to walk the Righteous Path violates another, he must be put to death.

You are to take him from even the altar of the Lord Above, who permits this so that he may die.

Originally Posted by Commands 13:10-16, 14:15-16

Those among the Righteous cannot be placed in bondage by another among the Righteous; for we Righteous are all slaves only to our Lord Above.

If one who professes to walk the Righteous Path should enslave, sell into slavery or purchase in chains his brother or sister in the faith, he must die.

Only if one among the Righteous intends to immediately set free a brother or sister in the faith who has been enslaved by foreigners, can he purchase him or her.

Your slaves must come from the godless around you; from foreign heathens, you may purchase foreign heathens as slaves, and to them you may also sell foreign heathens as slaves.

You may bequeath your slaves unto your children and your children's children.

If you sire a child with a slave, that child will not be a slave, but must be raised and treated as a full-blooded member of your Sept.

If one among the Righteous owes another a debt and offers to work it off, the debtor may become an indentured servant to his creditor.

But he must be released from indenture when he has worked off his debt, and even should he die in indenture, his debts will not pass on to his children.

Originally Posted by Commands 14:1-3

If a foreigner dwells among you, you must not mistreat him without due cause.

Instead, show him the hospitality you would show a guest from among your fellow Righteous.

As honey attracts more flies than vinegar, so too will kindness and open arms be more likely to compel him to see the righteousness of the ways of the Lord Above than cruelty and a closed fist.

Originally Posted by Commands 16:1-7

In times of war, if the Lord Above has delivered a heathen foe into your hands, this is what you must do.

You must raze their temples, destroy their idols, burn their sacred poles and kill all of their priests and wise men, so that your children and your children's children may grow old in ignorance of their heathen ways.

Unless otherwise commanded, you are not to slay those among their men who yield to you, but take them away in chains.

Unless otherwise commanded, you are not to slay their women and children who are not orphans, but take them away in chains.

You are to adopt any orphans below the age of four into your household, raise them as you would the son of a fallen friend, and ensure that they learn our ways without learning any of their fathers' ways.

You are to give any orphans above the age of four to the care of the Sept of Shur, where they are to be raised in our ways.

If you are one of the Shurim, you may adopt orphans above the age of four into your household, and personally teach them the ways of the Lord and raise them as if they are your own.

Originally Posted by Commands 18:14

Do not charge a brother or sister in the faith interest; not on money, not on food, not on victuals or anything else that may be lent on interest.

You may, however, charge interest on anything you loan to a foreigner.

Originally Posted by Commands 20:1-7

You must not lie with your neighbor's wife;

with women who you are not married to in general;

with your close kin;

with the beasts;

if you are man, with another man;

if you are woman, with another woman.

For these are all abominable in the sight of the Lord Above.

|

'Illami society was divided into seven tribes or 'Septs', each of which were further divided into clans comprised of dozens of closely-related individual families, and the chief clan of each tribe claimed descent from one of the seven sons of the 'Illami patriarch Bel-Hizzar, who gave his name to the overall Sept; Esoph, Kan'ah, Rechab, Deror, Vel'el, Sever and Shur. While in the 'Illami's early days each of these Septs functioned more or less like the average tribe within a greater confederacy, by the time of Elech they had become more like castes and factions within a more organized and hierarchical society, with each Sept being accorded a rank in the 'Illami polity, having a specific role for which they were raised practically from birth to fulfill, and being restricted in their marriage choices: one could only marry within at most one Sept above or below their own, and naturally in-Sept marriages were preferred. The father's Sept determined the Sept of his son or daughter. These Septs were supposed to work together for the betterment of the Righteous in general, and it was expected that their synergy and division of labor would produce an efficient and harmonious society.

The Esophim, whose leading Bet-Esoph clan claimed direct descent from Bel-Hizzar's eldest son and whose starry blue-and-white standard is thought to have been the flag of the 'Illami faith and nation in general (certainly it was flown above all other 'Illami standards on the battlefield), occupied the pinnacle of 'Illami society and were in effect a priestly caste. Esophim boys were required to study the Qabal from their third birthday onward, were taught how to read and write at the same time, and took vows to abstain from wine, grapes, liquor of any sort, and any substance (including vinegar) made from the above; to never cut their hair; and to never defile their hands by touching a corpse or grave, not even those of their close kin, at the age of twelve. By the age of fourteen they were expected to start reading from the Qabal to others and to have held at least one public sermon, and two years later they would be drafted into the Sacred Band, the sole standing regiment of the 'Illami army which served as temple guards in peacetime and an elite mixed corps in wartime, for a five-year period. Upon reaching their 21st birthday, one in every five Esophim boys would remain part of the Sacred Band, while the rest were formally ordained into the priesthood. They are thus also known as 'Those Who Pray'.

As clerics, they were responsible for reading from the Qabal and sermonizing to their flock every seventh day; for leading public prayers and major religious celebrations; for presiding over trials and sentencing criminals who had been found guilty by a seven-man jury comprised of randomly chosen men from each of the Septs, including a second Esophim; for anathematizing apostates, heretics and dissidents (exiling them from 'Illam, depriving them of the right to any sort of religious rite and making it legal for anyone to kill them on sight); and for counseling the Stewards together with the Kan'ahim and Rechabim. In matters of law, they worked together with the Kana'him The Esophim also, alone out of all the Septs, retained veto power over the election of new Stewards in this early period. Perhaps not by coincidence, most Stewards of the time (including Yuvel and Galad bet-Lior, first and last of the pre-Elech Stewards of 'Illam) were Esophim.

| Artist's imagining of an ordained Esophim priest in his white-and-blue robes, c. 10,500 AA |  |

The patriarchs (defined as the oldest living male, irregardless of his degree of kinship to the preceding patriarch) of the Bet-Esoph clan proper occupied a unique position, as the High Priests of old 'Illam. They were the supreme religious leaders of the Righteous Many, and no major decision (such as going to war) could be made without their presence. It was they who performed important animal sacrifices to please the Lord Above, who accompanied 'Illami armies to war to boost morale with further religious services, and they alone could initiate proceedings to depose a Steward whom they judged to be insufficiently pious and competent. High Priests were expected to remain aloof from the general populace except when conducting major ceremonies, and thus could not mingle with anyone outside of the ranks of the Esophim, be seen in public outside of his ceremonial robes and jeweled breastplate, or enter a public bath, for example.

| Meshul'el bet-Keshor, the High Priest in the time of Elech, in ceremonial garb c. 10,500 AA |  |

The Kan'ahim, whose leading Bet-Kan'ah clan claimed descent from Bel-Hizzar's second son, were placed directly below the Esophim on the 'Illami socio-politico-religious ladder. They were the designated scribes, scholars, physicians and book-keepers of the Righteous Many, and like the Esophim, were taught to read and write from a young age. Unlike the priestly Esophim, they were not permitted to conduct religious ceremonies. Instead, the Kan'ahim busied themselves with the writing and preservation of records & new copies of the Qabal on papyrus, writing letters for illiterate high-status 'Illami, jurisprudence, accounting, poetry, storytelling and treating the wounded or ill of 'Illam. In peacetime they also frequently participated in diplomatic missions alongside the Vel'elim, and in wartime they were 'Illam's chief siege engineers. They are accordingly also known as 'Those Who Write'.

The Kan'ahim standard was recorded as depicting a crown (representing the Lord Above, King of all Creation) above a golden eye and open hands (representing the observant Kan'ahim themselves & their duty to use their knowledge for the betterment of their fellow faithful), from which descended a winged and twisted staff (representing knowledge, given from above). Yuvel's immediate successor as Steward, Simcha bet-Tomer, came from the ranks of this Sept, as did Meit bet-Rotem and Eiran bet-Doron - two of the usurping triumvirs who tried to turn 'Illam from the narrow Path of the Righteous in the time of Galad bet-Lior and Elech bet-Eyal.

| Modern recreation of the Kan'ahim standard |  |

| A Kan'ahim scholar, c. 10,500 AA |  |

The Rechabim, whose leading Bet-Rechab clan claimed descent from Bel-Hizzar's third son, fell in line behind the Esophim & Kan'ahim. They were the warrior caste of ancient 'Illami society, with the boys training to fight and sparring with one another in training yards, racing in the riding grounds and competing in the archery ranges as soon as they could walk. In wartime, while all able-bodied 'Illami were expected to contribute, the Rechabim would undoubtedly provide the bulk of 'Illam's best troops, a solid core of professional soldiers that would form the center of any battle-line and around whom the men of the other Septs could rally around. On their sixteenth birthday, each Rechabim boy would be assigned to a specific battlefield role (determined by exactly which areas they excelled in during training) in which they were to serve for life; some became masterful skirmishers, but most were slated to become heavy infantry and cavalry, and thus form the heaviest fighting arm of 'Illam's hosts. Who got to serve as the officers of the 'hundreds' and 'thousands' (apparently regimental units within the Rechabim contingents) were decided in contests of strength, where dozens of the highest-born Rechabim would clobber each other in (non-lethal) sparring sessions, with the top three victors being made into commanders. Rechabim women were known to exhort their menfolk to either return with their shields or upon them, as well, and retreating in battle without explicit orders was considered so disgraceful that the man who did that would have little alternative to becoming a social pariah beyond suicide. They are accordingly also known as 'Those Who Fight'.

The Rechabim standard, as recorded in the Qabal, depicted a black-and-grey Lightbringer on a blood-red background, denoting their grim role as the bloody-handed defenders of the Righteous and the vanguard of their religion against all who have yet to be enlightened - whether it be by the word, or by an ax leaving a big enough hole in their skull for the Lord's light to shine through. Elech, the first of the hereditary Stewards of 'Illam and one of their greatest heroes, was one of the Rechabim - indeed he was the nephew of the Rechabim patriarch at the time, though on account of his relative youth when he attained Stewardship of 'Illam, he himself didn't become the Sept's official patriarch until he was 50.

| Modern recreation of the Rechabim standard |  |

| A Rechabim heavy spearman (with the shield that he's expected to return with, dead or alive), c. 10,500 AA |  |

The Derorim, whose leading Bet-Deror clan claimed descent from Bel-Hizzar's fourth son, were the fourth great tribe in 'Illami reckoning. They were the Sept of landowners or, as the Qabal calls them, 'lesser stewards' in charge of managing the lands of the Earth in the name of their Creator and true owner. The Derorim were thus one of the most powerful forces in the 'Illami countryside, a hereditary caste that ruled estates worked on by slaves and serfs from the Septs of Sever & Shur from manorial fortresses in a manner that was not all that dissimilar to the Shamshi Amyrs. In times of war, they were responsible for providing the army with horses and mules (and early on, camels as well), and typically fought as cavalrymen when required to serve in a more direct fashion. They are accordingly also known as 'Those Who Rule'.

The Derorim standard, as recorded in the Qabal, depicted a queen bee, which ruled its colony as they were expected to govern their feudatories. The only woman known to have served as Steward in the pre-Elech 'archaic' period, Atarah bil-Melelem, was one of the Derorim, and known to have been a staunch conservative who fought few wars (surprisingly, given the role of the early Stewards as warchiefs) but won all of those that she did fight, notably enslaved the entirety of the Had'ri tribe of rival Mun'umati upon defeating them around 10,410 AA, and collaborated with the Esophim to reinforce the divisions between & social roles of the Septs.

| Modern recreation of the Derorim standard |  |

| A Bet-Deror patriarch embraces his son, c. 10,480 AA |  |

The Vel'elim were the fifth Sept in 'Illami reckoning, and the Bet-Vel'el clan which sat at their head claimed descent from Bel-Hizzar's fifth son. Theirs was the Sept of merchants, explorers and diplomats, whose members were the first to be sent as envoys to foreign powers and freely engaged in commerce. The Vel'elim thus drove the construction of new road networks, frequently exhorted the Rechabim to keep said roads clear for trade or else saw to it themselves by hiring their own guards, managed trading caravans and seaborne or riverine convoys, arranged trade deals abroad, and shared the burden of accounting with the Kan'ahim. They also lent and borrowed from each other and members of the other Septs in addition to foreigners, though they could only charge interest on loans made to foreigners. They are accordingly also known as 'Those Who Trade'.

The Vel'elim standard, recorded in the Qabal, reportedly depicted a blue-and-white anchor with scales on a white-and-blue field. The one Steward known to have been provided by this Sept, Anat bet-Chabed, implemented the usage of seashells as currency among the 'Illami; besides that, they do not appear to have played much of a role in early 'Illami society, though the founding of Sa-Bel as a major trading port and fixed capital by Elech would tremendously strengthen the Sept in time.

| Modern recreation of the Vel'elim standard |  |

| A Vel'elim caravan winding through the countryside, c. 10,500 AA |  |

The sixth Sept of ancient 'Illami society were the Severim, whose primary clan of Bet-Sever claimed Bel-Hizzar's sixth son as their progenitor. They were the Sept of farmers, both freeholders who owned their own small plots of land (and who might even have a small number of other, less fortunate Severim working for them as hired laborers) and technically free tenant farmers who worked on the fields of the Derorim. Regardless of whether or not they owned the land they lived and farmed on, however, the Sever'im were effectively bound to it - freeholders always had to worry about envious neighbors breaking the Seventh Commandment and moving in on their farmstead while they were away, while tenants legally could not leave until they accumulated enough wealth to purchase their own plot of land and also found a willing buyer in a time period when few Derorim and fellow Severim alike wished to part with even a fraction of their estates. They are thus quite aptly referred to as 'Those Who Farm'.

Due to the Great Cooling and their more northerly location, away from the 'Awali floodplains and the larger Abanarir & Muryurir Rivers to the south, Severim farmers tended to grow wheat over rice (which remained the primary crop of the 'Awali and later Shamshi, at least at the mouths and sources of the two great rivers) and alongside barley. Accordingly, bread replaced rice as the staple dish of the 'Illami.

The Sever'im banner, recorded in the Qabal, depicted a black ox's head on a plain brown field. Fayna bil-Ilan, the chosen wife of the Steward Elech, was from a Severim family.

| Modern recreation of the Severim standard |  |

| Two Severim women chatting as they work in the fields with their families, c. 10,500 AA |  |

The last and least of the Septs in all but numbers were the Shurim, whose leading clan of Bet-Shur claimed descent from the seventh and youngest of Bel-Hizzar's sons. They were the tribe of servants and craftsmen, toiling away day by day for the other six Septs in various capacities: some helped their betters farm or fish or cut wood in the fields and rivers, others baked mud-bricks and thatched roofs for houses, and still others made simple clay pottery or worked as wet-nurses for the children of priests and landowners, et cetera. Despite its lowly position however, this Sept was also the largest, being the most likely to absorb new 'Illami - namely, the orphans of destroyed rival peoples who were then to be brought up in the 'Illami ways - and also the most flexible socially, as Shurite children would traditionally spend some years (usually between the ages of 11 and 15) in the service of a family from a higher Sept and could be promoted to that Sept's ranks if they sufficiently impressed their temporary masters. The Shurim were referred to as 'Those Who Serve' in their time.

The standard of the Shurim, recorded in the Qabal, depicted a plain black ant (quite fittingly, as it is a humble yet numerous and hard-working insect) on a light brown field. Of all the Septs, the Shurim provided few notable individuals and certainly nobody that ever came close to becoming Steward in the dark age of the Riverlands, but were noted to act quite effectively as a bloc when sufficiently oppressed or threatened by the higher Septs.

| Modern recreation of the Shurim standard |  |

| Shurim women carrying water jugs under the watch of a Rechabite overseer and a fellow Shurite guard, c. 10,500 AA |  |

Although the Septs were supposed to live in harmony and work together flawlessly to support one another & turn 'Illam into paradise on Earth, this was not always the case, to put it mildly. The general assemblies of the Septs to elect a new Steward when the old one died always promised to be rowdy affairs, and at these gatherings the Septs functioned more like political parties than castes or tribes: there were, after all, no secret ballots, and each caste voted as a bloc. Certain voting patterns and electoral alliances emerged: the three lower Septs would on occasion band against the four above them, and some assemblies devolved into violence - most notably the assembly of 10,158 AA, where the three lower Septs were unexpectedly joined by the Kana'him in their bid to get the Sever'ite Mat'el bet-Edan elected Steward; the Esophim, outraged at the unexpected defeat of their own candidate, exercised their veto, and as a result 'Illam was plunged into a nine-month civil war until the conservative coalition of Esophim, Rechabim and Derorim relented and a new election was held, where Anat bet-Chabed of the Vel'elim emerged triumphant as a compromise candidate. In another case of intra-'Illami violence, the Severim and Shurim joined forces in a major rebellion against the abuses of the Derorim around 10,400 AA, which ended only when the High Priest arranged another compromise in which he repealed most of the late Stewardess Atariah bil-Melelem's oppressive laws, banned the seizure of Severim farmlands while their men were off fighting in war and proclaimed that Shurim could not be flogged by their masters for not continuing to work after the sun had completely set.

When Elech consolidated the 'Illami state and founded Sa-Bel, he also set the stage for a sociopolitical realignment. The strengthened Vel'elim and many Shurim would find it natural to enter an alliance with the Kana'him, forming a commercial, progressive (by the standards of the time) and urban bloc that stood in opposition to the provincial and traditionalist alliance of the Esophim, Rechabim, Derorim and Severim; thus did the theme of general class struggle start to wane in importance compared to new struggles between urbanites and rural-dwellers, merchants and those who were bonded to the land or sword, and scholars who pursued worldly knowledge and clerics who searched for divine truths. But, that is a story for another time. |

| 'Illami religion | The Tansim el-'Ilm or 'Path of Righteousness', as the 'Illamites call their religion, is best defined as a Mainstream faith of Clerical soul and possessed of a Bastion-of-the-Faith mentality. It is known in far greater detail than the traditions of the Ahl al-Shamshi and Ahl al-Nebu, in large part due to how rigorously the 'Illami recorded and preserved its myriad strict teachings and ordinances in their holy book, the Qabal hith el-'Ilm or 'Teachings of the Righteous'. For this entry, only this first four books of the Qabal are relevant, those four being:

- The Book of Creation, detailing the creation of the world and humanity and the early stages of the eternal struggle between the Lord Above and His foes.

- The Book of Flight, detailing the captivity of the Righteous Many beneath the 'Awali, their war of liberation alongside their fellow Mun'umati, and their voyage to the Promised Land.

- The Book of Commands, a combination of restating the Twelve Commandments handed down from on high and the myriad laws written by the Esophim over the ages.

- The First Book of Stewards, detailing the reign of various elected Stewards over the Righteous between Yuvel and Galad.

Like the other Mun'umati religions, the Tansibet was explicitly monotheistic: the deity it revered was called Bel-Azer, the 'Lord Above'. It was said that He was one two beings that existed at the beginning of all things, and it was He who indeed created the material universe in six days before taking the seventh to rest, as outlined in the Book of Creation - the first book of the Qabal:

- On the first day, the Lord Above created light amidst the dark void that was the then-unborn universe - thought to not just be light in general, but also the sun, moon and stars in particular - and with this light He also created the host of angels.

- On the second day, to sate the thirst of His angelic creations, He created water and parted it from the firmament, creating sky and sea.

- On the third day, He and the refreshed angels created the Earth and planted upon it the great Tree of Life, the first plant on which all other life was placed and sustained.

- On the fourth day, He created all other plant life, which was tended to by the angels.

- On the fifth day, He created the beasts of the earth, sea and air.

- On the sixth day, He formed the first two humans from dirt and breathed life into them with a kiss: Ka'han and Sanna. To them He entrusted stewardship over the Tree of Life and all else that lived amidst its branches, while His angels retreated to Heaven.

| The Lord Above shapes the Earth in His hands |  |

However, despite His power, Bel-Azer is not said to be a completely omnipotent and omnipresent being, capable of doing anything. He has been opposed from the beginning of time by Bel-Bezar, the 'Lord Below', His equal and opposite who found that the light of the sun burned his skin and that the stars blinded him on the first day of creation; in a sudden fury he tried to push these sources of light out of his way, causing the first sunset and darkening Creation. When the Lord Above demanded he explain why he did what he did, the Lord Below instead reached out to some of His angels (as he was a purely destructive force, he could not directly create any minions of his own) and told them that together they could create a better universe than their Creator, one where neither he nor they would have to feel pain or discomfort; and so they went to war with Bel-Azer and those angels who stayed loyal to Him. The rebels were defeated and the survivors cast out from the light forever, to wallow in the abyssal darkness with their master, but there Bel-Bezar devoured them and proclaimed that though he may have lost the first battle of the two deities, their war was still on and would end only when he had corrupted or destroyed all of the Lord Above's creations.

While the Tree of Life grew above the earth, the Lord Below twisted together a dark and crude imitation in the form of the Lifeless Tree beneath it. Since the second and third days of creation, the Lords Above and Below have remained locked into an unending, evenly matched struggle for control of Creation and the souls of men: Bel-Azer being associated with the light, law & order, logic, peace and creative powers (essentially a divine manifestation of the superego), and Bel-Bezar being associated with darkness, chaos, violence, base emotions and entropy (essentially a divine manifestation of the id).

| Painting depicting the Lord Above chaining & casting the Lord Below through the Interstice and back to his abyssal lair |  |

Late in the seventh year of creation, Bel-Bezar slipped through the Interstice between the two Trees' roots and, disguised as another human, seduced Sanna away from her husband's side. He brought her beneath the earth, where he revealed his true face and took her by force until she broke beneath him. From what remained of her emerged their seven daughters, all but the youngest said to be 'abominations in human skin' who had their mother's looks on the outside but burned with their father's cruelty and malice (Creation, 2:4-10) - the first demons, though the last at least knew what was horribly wrong with her father and despised him. With these daughters he fathered a legion of monsters, who would serve as his warriors in the war against the Lord Above.

| The Lord Below tempts Sanna |  |

Meanwhile, Ka'han was naturally enraged at the abduction of his wife, and descended into the Interstice alone in an attempt to rescue her. Against the power of the Lord Below, he obviously failed, and had to be dragged away to safety by a legion of angels...though not before he got to see the mutilated remains of his beloved. Swearing vengeance, he asked the Lord Above to let him and his three sons dwell on the earth, just above the roots of the Tree of Life so that they could stand close to the Interstice's entrance - and thus, close to the home of their foe. The Lord warned him that by permanently descending from the higher reaches of the Tree of Life, Ka'han and his descendants would lose their immortality and be exposed to the diseases and elements of the earth below, but for the love he bore his wife and the righteous fury against the Lord Below that blazed in his heart, Ka'han persisted: thus did man come to age and die naturally. To compensate for his loss of immortality and the resulting inability to learn of every bit of knowledge the Earth might have, the Lord Above created more humans to assist Ka'han; at first, three girls who could grow up to become his sons' wives, but later hundreds, thousands, and finally tens of thousands more men who could help him gather resources and fight the minions of the Lord Below, as well as women with whom these new men could mate.

Since then, the human race has served as the vanguard of the Lord Above against His foes below the earth. However, there have been some...hiccups along the way, as living on the Earth has left humanity more vulnerable to corruption by both worldly things and the Lord Below than ever. Hiccups like Ka'han's eldest son Av'edan being corrupted by the Lord Below into murdering his younger brother Ben'eqeh in a fit of jealousy as they argued over who should lead humanity while their father's corpse cooled, or worse still when the descendants of Ka'han - bound by fear of death and an inability to learn absolutely everything there is to know - grew increasingly twisted by the machinations of the Lord Below and his demons in the centuries that followed this first murder. The latter culminated in Bel-Qa'mat, a hundredth-generation descendant of Av'edan, unifying the human race, sacrificing his own firstborn to the Lord Below and making preparations to tear open the seal between the Interstice and the earth to let demonkind invade the latter as a stepping stone to rest of the Tree of Life; the response of the Lord Above was to ravage the world with pillars of divine fire, and then send hosts of angels down to kill anyone who survived and wasn't among the ten thousand chosen innocents (interpreted as just children, split into 5,000 boys and 5,000 girls) who were hiding out in a flying ark, built by the 'last among the righteous' Y'nosh before Bel-Qa'mat's minions descended upon and martyred him. Bel-Qa'mat and almost the entirety of the corrupt human race obviously died as a consequence, allowing these innocents to inherit the Earth and build a new, hopefully purer society atop their ashes.

| "And in His righteous wrath, the Lord Above rained fire, rock and choking smoke upon the Earth for forty days and forty nights..." (Creation 9:9) |  |

Twenty generations after this 'Flame Deluge', the descendants of the Ten Thousand Innocents had multiplied and united into a second Kingdom of Men, and invaded the Interstice & Lifeless Tree under the leadership of their proud and mighty king, Bel-Bel'iq. While the angels cleared a path for them through the Interstice, they were able to take the fight to demonkind for the first time and compensated for their individual lack of power with numbers, zeal and technology ('swords, axes, spears, hammers and daggers of iron, and all the panoply of war' - Creation 10:4), killing 'many multitudes of abominations' and forcing even the Lord Below himself to surrender at the taproot of his Lifeless Tree (Creation 10:1-30). Yet Bel-Bel'iq did not kill the Lord Below on the spot as the angels counseled, but instead took him back to the surface in chains and kept him as a prisoner, serving forever as a reminder of his power.

The Lord Below promptly manipulated Bel-Bel'iq into freeing him from his chains and making him an adviser, then whispered lies into his ears to turn him against the Lord Above; that the Lord Above was actually a tyrant keeping humanity weak and ignorant by preventing them from realizing their full strength, that his ancestor Ka'han had actually been cast out of the higher branches of the Tree of Life, and that with the demons he could crawl back up said Tree, reclaim his birthright and defeat death. Bel-Bel'iq ordered the construction of a great tower, high enough to reach the lowest branch of the Tree of Life, though he told the truth about his ambitions to only a few and deceived the majority of his subjects, telling them that the tower was just to let him communicate more directly with the Lord Above. Unfortunately for the King of Men, he didn't count on the Lord Above being able to see through mortal lies; another host of angels promptly descended upon the tower as it neared completion, and in the ensuing battle Bel-Bel'iq was killed with his fellow conspirators and their most loyal soldiers, while those workers and overseers who had remained ignorant of his true intentions simply scattered in fear with their lives. The Lord Below fled back underground and reclaimed dominion of his own demonic subjects, while the Lord Above sundered the ancient common tongue of men partly as punishment and partly to ensure they could never be directed to a single purpose as Bel-Bel'iq had done, causing the disintegration of this united human empire into a mass of feuding tribes speaking in tongues that were incomprehensible to one another.

| Well, this certainly could have ended better for Bel-Bel'iq |  |

According to the 'Illami, it is critical for all humans (but especially them, as the people specifically chosen by the Lord Above to be His vanguard of righteousness) to do their utmost to thwart the schemes of the Lord Below and weaken him to the point that the Lord Above can destroy him utterly at last, both metaphorically by following the Righteous Path laid out with the commandments of the Lord Above & the laws of the faith's elders - and more directly, by seeking out and converting or destroying heathens, whose false gods and spirits are considered nothing but the myriad disguises of the Lord Below and his demonic minions. No less is demanded of them, and they must do these things proactively lest the Lord Below regain enough of a foothold to drive humanity to repeat the sins that resulted in the Flame Deluge and the Great Sundering. Bel-Hizzar may have been the first man to whom these truths were told, but Yuvel is honored as the First Prophet for having received the Twelve Commandments, actually reached the Holy Land and organized the Righteous into a sufficiently coherent society to enforce and spread their teachings on a large scale; it is also prophesied that some day into the distant future, the Lord Above will send a Second and Third Prophet to further guide the Righteous Many into His light, and lead them in cleansing the earth of sin & sinners.

| The role of the clergy | As one might guess from its characterization as a Clerical religion, the clergy were of tremendous importance to practitioners of the Path of the Righteous. Drawn exclusively from the Sept of Esoph, early 'Illam's ordained clerics were responsible for directing rituals and religious services every seventh day of the week, administering rites, advising and deposing Stewards as required, and serving as judges.

Some of the rites administered and rituals or holy days presided over by the 'Illamite priests included:

- Bet Ch'yot (for boys) and Bil Ch'yat (for girls): Upon reaching their thirteenth birthday, every 'Illami boy and girl is considered old enough to be held responsible for their actions, and is to be fully confirmed into the ranks of the Righteous in a ceremony presided over by the priest. They are ritually baptized in a specially-prepared bath; anointed with the sign of the hexagram in holy oil; swear vows to serve the Lord Above, to follow His commandments and the laws set down by His priests (who are His voices on the earth, after all) and to oppose the Lord Below and his servants at every turn and all costs; and (in the case of young Esophim boys) permitted to read a chapter from the Qabal to the rest of the community, all of which are done in sight of their community. Once this is all done, the community can celebrate, with the newly confirmed youth being allowed to taste wine for the first time at this celebration of their coming-of-age.

- Ekhen, Shekhen and Sefet: 'Illamite marriages must be presided over by an ordained priest to be considered valid in the eyes of the law. First, the man and woman must enter a formal betrothal at a ceremony called the Ekhen (signing), where they announce their intent to marry within seven-times-seventy days before a priest and at least two witnesses (one from the groom's family and one from the bride's) while a Kan'ahite scribe records their vows and writes up a marriage contract on a papyrus scroll. The Shekhen, or 'binding', is the actual wedding ceremony itself, where the groom & bride speak their wedding vows to one another, are literally tied together at the wrist with an ornate ribbon, seal their love with a kiss and proclaimed husband & wife by the priest. Normally, 'Illami can only take one wife (though nothing prevents them from engaging in amorous relations with a slave...) and can never divorce, though in cases of spousal abuse or political inconvenience the priest who married them can also issue a document of divorce called a 'sefet', or 'separation'. (divorces seem to have strictly been something for the 'Illamite elite, however; those of the lesser Septs were truly wedded 'til death did them part, and adultery was to be punished with death for both the adulterer/adulteress and their extramarital partner with no exceptions) There have also been a few unusual cases of men taking multiple wives in the Qabal, most (in)famously Elech bet-Eyal, who married two women - though, considering the consequences of his two marriages, that was definitely not supposed to be a good thing, and likely a warning against polygamy in general.

- Shomayn: When an 'Illamite has died, he or she is supposed to be buried, returning to the earth from which his progenitors were made. A priest is required to purify the body with special oils and blessed water, dress it in a pure white burial shroud, lift it into a plain casket (regardless of rank in life, all are considered equal in death) with the help of the deceased's kinsmen and friends, and finally pray that the Lord Above forgives the transgressions of the deceased, welcomes his or her soul into Heaven and looks after his or her surviving kin as the casket is lowered into the ground and buried. The rite of shomayn must be administered if the soul of the deceased is to have any chance of ascending upward into the branches of the Tree of Life and find eternal salvation, otherwise they will surely be doomed to wander the Interstice as a lost and confused spirit until the end of time.

- Yam Chag: Every seven days, the community would gather in their local temple to the Lord Above: the men would immerse themselves in a small bath called the neyilah, after which they would enter the main chamber and be seated to hear the local priest read from the Qabal, and then deliver a sermon. They were invited to discuss and debate the day's verses after the priest had finished delivering his sermon. Women had to wait in an antechamber until the men were done, after which they would do the same in a different neyilah and enter to hear the exact same reading and sermon; however, unlike the men, they could not discuss the day's reading. Children who had not yet undergone the rite of Bet/Bil Ch'yot were read to last of all (in the event that the priest did not deem the verses he read out to the adults suitable for children, he may read an entirely different set of verses to them instead), and were also forbidden from debating whatever verses the priest had deemed child-appropriate for that day. No work was allowed on this holy day, which was to be a day of rest, relaxation and introspection.

- Elisan: The 'Illamite New Year, considered a special time to curse the Lord Below. Meat is served in great quantities, to physically strengthen the Righteous for their struggle with this immortal enemy, and everyone in every town is expected to stone an idol depicting the Lord Below in the sight and with the approval of their local priest.

- Beresit: On the first day of spring (traditionally, the first day of the fourth month in the 'Illami calendar) the 'Illamites have their great festival of lights, celebrating the creation of the world by the Lord Above and offering up prayers that His divine Light might prevail over the darkness of the evil Lord Below. Homes are to be cleaned and decorated with designs of flower petals & colored sand at least a week in advance of the festival. When the sun has set, every family in every town and village is to light seven oil lamps, candles and/or lanterns arranged in a hexagram pattern around their dwelling. Then they are to congregate before the nearest temple, around which the priest and his family have also lit up a hexagram with braziers and hung their own great decorated tapestries, and receive a blessing, a reminder of the Lord's acts of creation, and issue prayers to strengthen His hand in the war with evil before engaging in feasting and merriment. Each family, the priest's own included, is meant to bring their own food to eat and share, and outside observers noted that the normally stoic and strait-laced 'Illami really cut loose on this day. As the Shamshi 'Ibar bar al-'As reported when his travels took him to the 'Illami village of Horon:

Originally Posted by 'Ibar bar al-'As

On the day which they call 'Beresit', the people of the north, whom I had found to be joyless and stern most days, truly came to life after the Sun had gone down. Amidst the dazzling fires set by their priest, the villagers indulged in all sorts of meat and vegetable stews, sweets, and fresh-baked bread with aplomb. Three great oxen had been butchered and roasted for the festivities, and the priest had bought a cart of salt and herbs with which to flavor their flesh; I must confess, his wife and daughters cooked the oxen most excellently, and even managed to make a good soup out of the beasts' tails. Wine flowed freely and plentifully.

I found the local landlord rubbing shoulders with men he'd normally be exhorting to work harder in the fields or threatening with the scourge. The priest himself, whom I thought could not smile, sat loudly laughing and joking with some of the town's men while in the midst of what must have been his tenth cup of wine that night. Men and women who would normally not even be allowed in the same chambers in their temples could openly dance, embrace and kiss beneath the stars. Some of the youths of the village snuck off, away from the fires, to engage in amorous activities.

...

The next day, it was as if the events of the previous night had not occurred, and everyone in the village had gone back to their old dull selves.

- Tzen: A 30-day fast held between the late summer and early fall, commemorating a fast undertaken by 'Illami ancestors in the last month of their captivity under the 'Awali. All the food in every town was to be gathered at the temple and kept under lock & key by the priest, who would distribute just enough portions to everybody thrice a day to keep them from starving. The fast was to be broken with a lavish celebratory feast and dance halfway through the ninth month of the year.

- Besh'e: The summer solstice is also the day on which the 'Illami commemorate and repent for the centuries of sins that their ancestors engaged in, leading up to the Flame Deluge. On this day of mourning, all the community - even the priest - go barefoot, don sackcloth, wipe ashes over their cheeks, and at night they shout, pray and wail for forgiveness and guidance to the Lord Above while marching in a hexagram formation around a massive bonfire, with the priest himself leading the procession. All healthy adults are required to abstain from food and alcohol all day, save a loaf of bread and an apple (said to be the first fruit encountered by the Ten Thousand Innocents after the Flame Deluge's end) at lunch, though they may still consume water.

- Ir'at: The winter solstice is also the day on which the 'Illami commemorate and repent for Bel-Bel'iq's folly, mankind's collective failure to off the Lord Below when they had the chance, and the disastrous chain of decisions that led up to the Great Sundering of humanity's ancient common tongue. All must spend the day barefoot, avoid bathing and the use of perfumes & lotions, and abstain from food, drink (except water, which is permitted) and sexual relations for a 23-hour period, instead dedicating all of their time and energies to prayer. In the last hour of the day, the community gathers at the temple to bask in the light of seven braziers, arranged in a hexagram, and the priest leads them in one last prayer of repentance for their ancestors' sins and their own, followed by a prayer beseeching the Lord Above to forgive them their transgressions even if they are not worthy, and break their fast on roast bull and goat (although no wine is permitted until the next day). |

| Bastion of the Righteous | As one can also guess from the characterization of its mentality as a Bastion of the Faith and from the commandments warning against apostasy & idolatry, the Righteous Path was a highly exclusive and insular religion, mirroring the general xenophobia of 'Illamite culture. One could not convert to the Path as an adult, but instead had to be raised within the faith and hear its teachings from as early in childhood as possible; hence why the (probably orphaned or soon-to-be-orphaned) children of enemy nations could be adopted into 'Illamite families and raised as 'Illamites, but everyone in their teen years and above were to be killed or enslaved. And as the Book of Commands made abundantly clear, there was no leaving the Righteous Path, either; apostates were to be killed on the spot, and if the person who butchers them is their own kin, all the better, for the Lord Above approves of the sort of man who would put Him above their own sinful blood relations.

While men were permitted to ask questions of and debate readings with the priest on Yam Chag, the priest's word was final when it came to doctrines, interpretations and the lessons to be learned from the day's readings. Further pressing the issue could lead to a stern rebuke in front of the entire community, or worse, anathematization: casting the troublesome individual out of the community, denying him or her rites, and effectively outlawing them by allowing anyone else to kill them without repercussions. An anathema could only be lifted by either the High Priest himself or the priest who issued it (or if he has died before the anathematized party, his successor).

While Commands 14:1-3 teaches believers to be welcoming to foreigners and not to kick them out or kill them without provocation, this had its limits. Foreigners could still be taxed, loaned to at interest, and expect harsher sentences than 'Illamites for the same crimes (ie. the death sentence, instead of 'just' having a hand lopped off, for their first theft). They were also strictly forbidden, under pain of death, from preaching or publicly practicing their heathen religions while in 'Illamite territory. In more extreme cases, there have been stories of 'Illamites from the higher and more conservative Septs who went as far as to discriminate against other 'Illamites - born to 'Illami parents - just for having been born outside of 'Illam's borders: many were opposed to the Stewardship of Anat bet-Chabed because his Vel'elim parents were trading in an 'Awali city under Shamshi suzerainty when he was born, for instance (1 Stewards 4:6-7). Marriages with non-'Illamites were not actually illegal, but they were heavily frowned upon (even when the prophet and Steward Yuvel did it) and the 'Illamite involved could expect at least temporary ostracism for going through with it, especially in the case of 'Illamite women marrying non-'Illamite men. |

| The 'Illamite calendar | | The 'Illamites measured time from the creation of the world by the Lord Above, which they purported to have occurred 4,000 years before their war of liberation against the Shamshi around 10,000 AA. Therefore, instead of that war ending in 10,015 AA, as far as they were concerned it ended in 4,015 Eblath-Keris (After Creation), or EK/AC. Theirs was a lunisolar calendar, with twelve lunar months (whose beginning & end was determined by the new moon) in an approximately 354-day solar year, further divided into 7-day weeks. |

| The Tree of Life and the Lifeless Tree: Salvation and damnation | The Tree of Life and its under-world mirror are generally understood to not be literal and physical constructs, but metaphorical and spiritual/extra-dimensional ones by orthodox 'Illami priests. The Tree of Life in particular is divided into seven 'branches' or she'voti-mi (singl. she'vot), each corresponding to an order of angels and representing a virtue that must be expressed & held by believers in order to reach salvation. Those who have embraced all of the virtues to the fullest, in so doing submitting themselves wholly in mind, body and soul to the Lord Above, become those most like Him and are permitted to ascend to the topmost she'vot, Shem'el, where they will live in proximity to the Lord Above Himself. These branches are:

- Shem'el: Heaven, the very peak of the Tree of Life. It is said to be a dimension of boundless light, where the sun shines unceasingly in a stark white sky, and where 'all that is pleasing to the eye' grows in abundance: great grass fields and flowery meadows, majestic trees taller than any tower, every fruit that pleases the tongue, and flowers that produce a nectar that tastes of milk and honey. Rivers whose fresh water purifies all disease and aging flow throughout the land, and so all who dwell here do so as immortals who want for nothing. The Lord Above Himself resides in a temple of sparkling crystal, so great and glorious that it brings to tears all who see it for the first time, and is attended upon by hosts of angels and saved humans alike who praise His name day in and day out. The souls of those humans who die after first mastering all seven heavenly virtues reside here. This she'vot is associated with the Lere-bel'im or 'lesser lords', the first and greatest of the angels, who are described as seven-winged and seven-headed beings the size of a small mountain.

- Hi'mel-el: The abode of the meek and the humble, set below only Shem'el. Here, those who were wise enough to accept that they are not the center of the universe and that they are but subjects of the Lord Above live their second lives out in paradisaical conditions, the only distinctions from Shem'el being that the sky is still blue and that the Lord Above does not reside here. This she'vot is associated with the Orim, the second order of angels, who are said to have the mane and body of a lion; the legs of a dragon; the tail of a scorpion; six eagles' wings; and the face of a man.

- Req'a: The abode of the patient, also set below Shem'el and opposite to Him'el-el. Those who were able to control their emotions in the face of great adversity all their lives reside here, within a vast desert where oases are plenty and the sun is not too hot. This she'vot is associated with the Tayyim, the third order of angels, vast winged white orbs covered in eyes and mouths that know all things earthly and divine & unfailingly speak in a calm monotone.

- Ger'et: The abode of the diligent, set beneath and connected to Hi'mel-el and Req'a. Those who tirelessly worked for justice and to make the lives of their fellow men better all their lives dwell here, amidst rolling plains and clear streams where they may enjoy eternal rest. This she'vot is associated with the Eshm'alim, fourth of the angelic choirs, four-winged and four-armed humanoid angels that wear crowns and elaborate shawls, and carry in each hand the Qabal, a scepter, a sword and a hexagram pendant; symbols of earthly authority and holiness, with which they steward the earth in their Lord's stead.

- Shekinah: The abode of the kind and gentle of heart, set below and connected to Ger'et & opposite to Erenech. Those who went out of their way to aid those in need, never had a bad word to say, loved others unconditionally and showed mercy even when it was undeserved dwell here between gently rolling hills and verdant forests. This she'vot is associated with the Me'etim, the fifth angelic choir, androgynous four-winged angels with gentle faces & musical voices who wear crowns of flowers.

- Erenech: The abode of the brave and zealous, set below and connected to Ger'et & opposite to Erenech. Those who died in defense of the faith and faithful reside in this land of iron towers, living spartan but not totally uncomfortable lives, and many go on to enter the lowest orders of angels themselves. This she'vot is associated with the La'wim, the sixth of the heavenly choirs, steel-skinned humanoids the size of giants with four wings (each covered in sharp, metallic feathers) and fiery eyes who march about in the panoply of war and serve as the vanguard of the Lord Above against the hordes of the Lord Below.

- Yus'had: The abode of the chaste and temperate, set below Shekinah & Erenech. Those who lived their lives in observance of the commandments on temperance, abstaining from excessive consumption and sex, reside here after they die, in a paradise that is said to be 'most like Earth' out of all the she'voti-mi but at unending peace. This she'vot is associated with the Hal'akhim, the seventh order of angels, twin-winged humanoids with jewel-like eyes and long scepters that are comprised of a golden head and iron rod.

At the foot of the Tree of Life lie the Earth and below that, the Interstice that separates the roots of the Tree of Life from those of the Lifeless Tree. The orders of angels that were once men, but willingly forsook their shot at eternal happiness to become the footsoldiers of the Lord Above in His war with the Fount of Evil, dwell here among the human race that they once belonged to: the Denayim and Ha'nim, divine soldiers and messengers respectively, who look exactly as they did in life but are now blessed with a pair of white feathery wings. The Denayim, in addition to guarding the Interstice with the La'wim, are the Lord Above's first response force to the presence of otherworldly evil on the face of the Earth, while the Ha'nim interact with and watch over mortals.

| Painting of the Tree of Life, which believers must (metaphorically and spiritually) climb to reach salvation |  |

Beneath the Interstice lies the Lifeless Tree and its own she'voti-mi, crawling with all sorts of demons who torment and gnaw at those who died in sin: there is one she'vot each for the gluttonous and lustful, the cowards, the cruel, the slothful, the wroth, the proud and those who have managed to check every item on this list of vices, mirroring the she'voti-mi of the Tree of Life, except all of these are terrible places of torment and gnashing of teeth. The cruelest and foulest of sinners are offered a way out of eternal torment, by forsaking whatever remains of their humanity to enter the two lowest and most human-like ranks of demonkind - Sha'nim and Patachim, tempters and 'the expendable', who are respectively tasked with infiltrating mortal society to sway men from the Righteous Path and with throwing themselves at the Interstice until they die again on angels' spears and blades or manage to open a breach.

| Artist's rendition of lesser angels and demons clashing in the Interstice |  |