Thank you Alwyn! Battles indeed were very lossy, hard to imagine today...

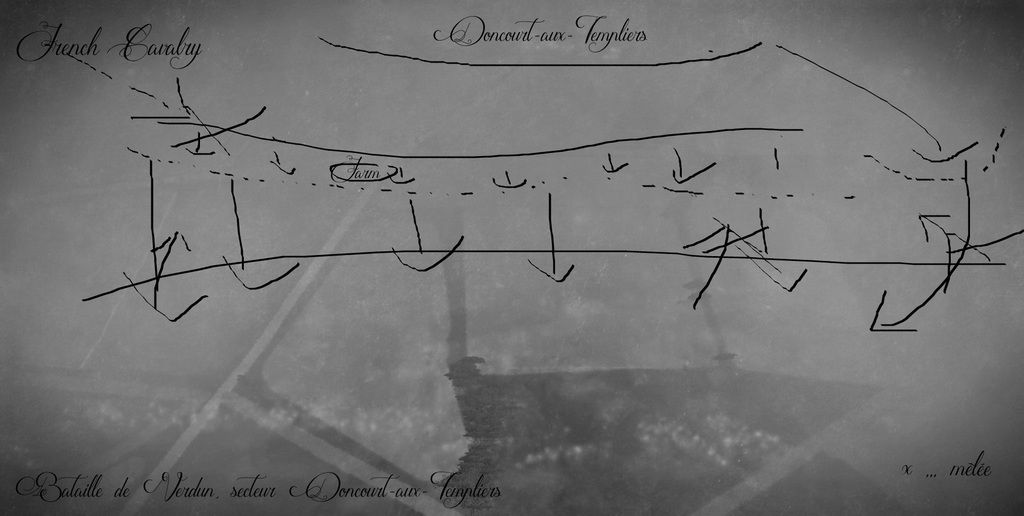

Chapter Ten: Bataille de Verdun [Secteur Doncourt-aux-Templiers]

"The German artillery and we were exchanging shells for hours while our infantry approached Doncourt-aux-Templiers the same way we did in Dommartin-Dampierre. They stopped at the height of a small farm where they started do dig ditches to wait until the order to assault is given. These ditches were hip-deep to enable shooting while kneeling at possibly attacking enemies also they were just outside the reach of the German rifles. More than a quarter million men were now awaiting the order to charge while we from the artillery tried our best to spot the enemy and weaken their lines. The biggest threat for us artillerymen were the 150mm shells of the German howitzer. These left enormous shell holes wherever they landed after flying shrieking through the air. Furthermore, what they lacked in firing rate was compensated by their range and angle of fire. We thought in the beginning that we had spotted them and shot industrious our 75mm at them until someone from the reconnaissance came and said that the enemy batteries were behind a hill outside of our range. So we could do nothing but shooting at the German lines and trying to ignore the heavy shells. This was, as you might think, not that easy. And the possibility that a shell landed next to us did exist.

Therefore we started, after receiving word that three of our guns had been destroyed by a shell, to dig ditches for us too and use earth to put up smaller defences around our cannons leaving gaps for the cannon tubes. This defended us at least against shrapnel shots but the 150mm were still a threat. Some even experimented a little bit and tried to increase their shooting angle by building a ramp on which the rolled the cannon, though captain Mallarmé didn't like this idea. Nothing else had happened by the evening of the 21nd except from the cannonades and smaller skirmishes, none of our skirmishing lines weren't allowed to advance until the cavalry which was supposed to attack the enemy right flank was in position but the cavalry officers wanted to wait until nightfall to deploy since the enemy's eyes were sharp during the day. The Germans had, further north, in Verdun, assaulted Fort Douaumant and Fort Vaux but without any great success - general Séré de Rivières did well in building the fortresses around the city.

The following night was ice cold, probably the coldest of the year, even more since we had nothing but the clothes we wore and the earth we lay on had the temperature of general Foch's heart; ice cold. Nonetheless, the night ensured us safety from the shells for the time being and we somehow managed to fall asleep even though the chattering of my freezing comrades gave me a hard time to do so. There was, however, suddenly a loud noise in the distant but after we jumped up with our rifles in our hands we realised that it was machine gun fire , it stopped after a few second. Nothing else happened the night, I think - at least not in the sector Doncourt-aux-Templiers. Well, we were more anxious to fall asleep.

We woke up aware that today that the real fighting was supposed to go down, for me the fact that I wouldn't anticipate in it made me feel anxious but I always kept my rifle close by, just in case. I can still remember the cannonades in the morning of that day, some shells hit close to our position and two of my comrades were wounded by splinters and one, Paul Pierre, a nineteen years old son of a winemaker, took one to his head and died on the way to the medical officer. I didn't know him that good but I think he had a fiancee back home.

Anyway, after shooting for a while I looked at the battle field just in time to see our cavalry charging at the enemy skirmishing line which had advanced towards our line. It was surely an impressive sight. Seeing the masses of men moving towards eat other while the sky above them was filled with small, white clouds left by shrapnel shells. Yet the charge was ... The charge did not have the intended effect I think, it seemed no one had learned something from the war of 1870. As one might expect when charging the enemy right flank while only the centre of them is fighting, meaning the right flank had time to look around ... The charge was a complete disaster. Some Germans saw the charge coming and fired two or three volleys within ten second it took the horses to cover the distance into the mass of riders which either fell dead or wounded from their horses and were stamped down or lost their horses to a bullet while galloping at full speed, I guess I don't have to mention that both cases had remotely the same ending. Nonetheless did the cavalry manage to reach the enemy firing line where they were greeted by the Germans and, well, their pointy bayonets. It was impressive to see with what ferocity the cavalry fought even though it had been halved by the three volleys they still managed to lutter à outrance [fr. fight to death ], so to say. Our left flank advanced in the meantime, something they should have done earlier but didn't for some reason. It was the officers of our left flank who couldn't follow the order to fire at the enemy right flank to give the cavalry the cover they needed. On the other hand, as Arthur later told me analytically, it was the incapability of the cavalry officer to adapt to a change of plans, the idea of direct command from the general to the officers was not realistic, at least not in 1914 nor in the later years. As a matter of fact, the French army never greatly changed it's doctrine of mission-type tactics sine 1815 which already proved fatal in the battle of the Marne despite the victory.

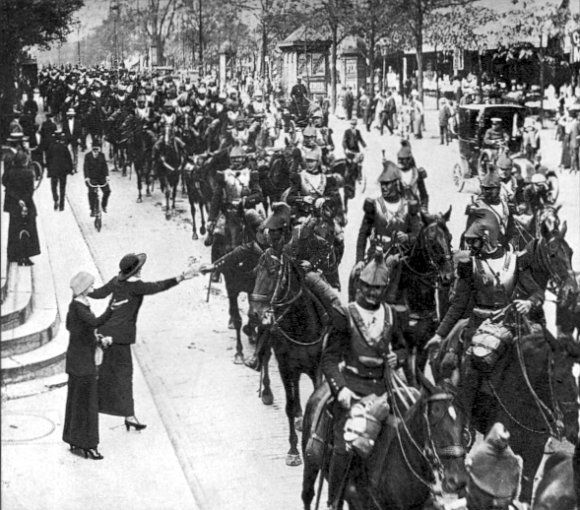

Painting of French cuirassiers

Painting of a French Hussar fighting a German infantry man

And the simple infantryman, or in this case the cavalry, got to feel that. They fought but it was a hopeless fight for them. Only a handful of cavalrymen and horses were alive by the time they fled or surrendered. Yet the cavalry allowed our infantry on the left to safely push forward and fire at the distracted Germans. From there on the battle turned into hours of simply shooting, same for the artillery and infantry. In the end, it was already late afternoon I think, broke our lines. A German machine had gun proned on the roof of a small farm between us and Doncourt-aux-Templies depleted our skirmishing line and our infantry fled under the pressure of the advancing German infantry. Now, without any riflemen to hold the enemy back came the Germans closer to us artillerymen. We hastily limber the guns up and tried to fall back but it wasn't that simple. First of all, the guns were heavy and it took us a long time to limber them up. The limbering-process was complex, along with. You had to get the horses to stand quietly in the right position, keep them calm while shells are falling around you and gunfire filled the air. Then you needed five or sic strong men to turn get the cannon in the right position and fixing the gun fast complicated and demanded a lot of prestidigitation. All of this was complicated without the time pressure but now now with the Germans getting closer...

Another problem was the forest - it had been hit hard by artillery shells and thus had many shellholes which we had to circumnavigate. We weren't even halfway through the forest when the first bullets whistled past our ears, so I decided to take some men and try to hold back the approaching enemy as well as in any way possible.

Photography of two Germans shoooting

There were sixty of us ready to sacrifice themselves for our comrades, one of them was Henri who didn't hesitate to "report for duty", as he put it. We used the shell holes to get cover and fired in the direction of the enemy. In order to trick the enemy that there were more of us we previously had asked our men who retreated with the guns to give us their rifles. Each of us lay two rifles next to each other on the ridge of a shell hole or on a branch and fired both. It was nearly impossible for us to actually aim that way but our intention was to hold the enemy back as long as possible. Another problem was the recoil. When I shot two rifles at the same time and tried to take the recoil with my left and right shoulder I almost was pushed back by the forces and my back hurt after three or four volleys, but it looked as if it actually worked because the Germans didn't seem quite inclined of advancing as fast as their should have and used the trees for cover instead. After hours of fire fighting, at least I perceived the thirty minutes it actually lasted as hours, so, after half an hour of fighting realised our opponents that there weren't quite as many of us as it seemed. So they charged forward with a loud "Hurra!" and we, I think there were only about twenty of us alive, fled. I saw Henri getting hit in the back while running. So I stopped and attempted to carry him but he said that I had to retreat. I, however, grabbed him and carried him shoulder high. He was surprisingly light and we got pretty far until a German, seemingly out of the nowhere, suddenly was behind us and thrust his bayonet in Henri's body. I fell to the ground and Henri fell ontop of me. I somehow managed to get him off me, jumped on my feet and whipped my bayonet out. I did no longer have a rifle to attack it to so I held it like a knife ready to take on the German in front of me. He had the clear advantage of reach and I knew that I couldn't afford to stay there in the forest any longer so leaped forward, dodged a thrust and rammed my bayonet into his right arm. His scream was maddening, clearly Germans and Frenchmen had different gorges.

Pulling it our was hard due to the modification Henri did two days before and a sort of struggle with the now screaming German threw me out of balance and when I finally managed to remove my bayonet from the German whole flaps of flesh got caught in the saw tenth and his blood was gushing out of the wound. Then I turned around and ran away neither interested in the flaps of flesh nor in the screaming German lying on the ground. This small fight made me completely forget about Henri who probably wasn't dead by that moment - leaving him for dead ... leaving this boy who just had finished school to die is something I regret to this day but back then in the moment I heard the Germans screaming "Hurra!" while combing through the forest made me feel more frightened than ever before and I simply stood up and ran away. I left the forest after a while and suddenly had to throw up - the picture of the screaming German and the thought that I left poor Henri to die was too much but I did know that I had to get away as fast as possible.

The retreat through the forest ... was a close call

Well, the rallying point was in Souilly but I somehow ended up in Beausite again where I met the 22nd infantry battalion -well, what was left of them- which was about to cover a retreat to Bar-le-Duc. The 22nd were punching holes into the people's houses for some sort of loopholes and digging ditches through on the streets and around the village. I also had to find out that the hill from which I had such a beautiful view over the surrounding area a few days ago had been riddled with shell holes and now was used as a position for a machine gun.

And just in the moment I was about to start out for Bar-le-Duc, I had a short break in Beausite, a German artillery shell exploded on the street right in front of me. I was thrown against a wall and lost my consciousness."

Notes:

Raimond Adolphe Séré de Rivières (1815 - 1898) was a French general. He was involved in building the fortresses around Verdun.

Battle of Verdun: Probably one of the most famous battles of WW1, as well as the longest. There are two common hypotheses why the battle was fought. One is, that Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of Staff, wanted to attack where he knew that the French had to defend at all cost thus using up alle their soldiers, as he said. Another one, and I personally think this one is more likely, is that he only said this because his attack in Verdun failed and needed an excuse why that happened. Verdun itself has several strategically important hills. (two very contested ones were Côte [height] 304 and Côte Mort-Homme [Dead man]. The battle lasted roughly 300 days and during these 300 days 14,000,000 shells were shot (32 shells per hour), 310,000 men died (43 per hour) and in the end the front changed about 4 kilometers, so it basically ended where it started.

The actual battle happened in 1916 but in-game it accured that I had to fight on the map where Verdun lies... I will see if I can get a second battle there (there is a special Verdun map in the custom battle menu)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote