As to the Pilum, however; I disagree regarding energies. Take a look at this thraed and its sources:

For example of how non-Olympic experienced throwers throw, see Sir Baldwin Spencer's

Native Tribes of the Northern Territory of Australia. Spencer wrote that men in community on Melville Island managed to throw a ten-foot, four-pound spear 104-143 feet (31-43.6 meters). So the worst thrower in this test, throwing by hand, did as well with a much heavier projectile as the folks with the ankyle.

However, the Melville Island throwers had a running start of up to twenty feet, while the ankyle users could only take one step forward. Come to think of it, that could easily account for much of the difference right there.

Looking at it some more, I think the high-speed camera failed to accurately record the throw velocity. According to

this calculator, a projectile released at 5.4 m/s at a 45-degree angle would attain a range of less than 3 m in a vacuum. You need about 17.5 m/s to reach 31 m - and air resistance would increase that.

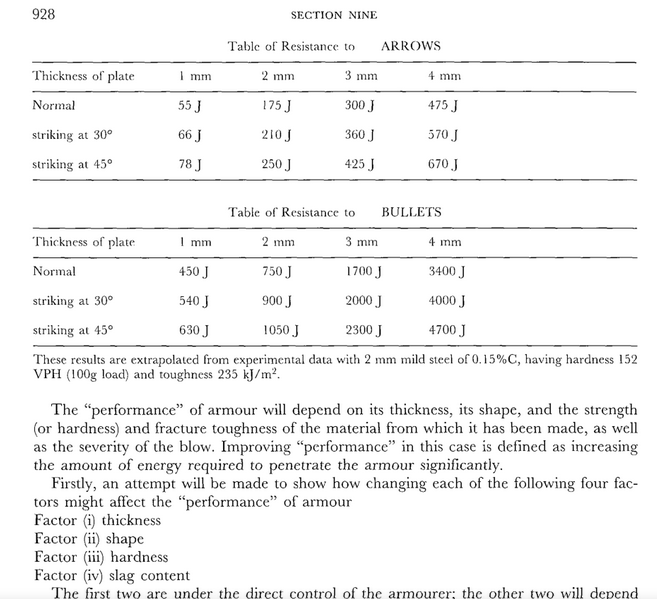

As an aside, Spencer's numbers support the notion that at least heavy spears/javelin could penetrate armor. Even the shortest throw probably had over 300 J of kinetic energy initially. This stands consistent with Vegetius's claim and has long made me wonder why thrown javelins or spears mostly fell out of use in the sixteenth century.

http://myarmoury.com/talk/viewtopic....&view=previous

Calculate the Australian figures together and you get roughly a 500-600J range. However, the important thing to note about pilum compared to crossbows is that the short trajectory of the projectile means that it bleeds off energy quickly, meaning that impact energies could be much less, and that the total range achieved is minuscule compared to the crossbow.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote