-An "Idea" is not having to be an actual depiction of something. You seem to argue that the idea of a circle is in tautology with a visual imagining of a perfect circle. While some may try to have such a thing (itself quite problematic; are you really imagining something that factors an irrational number so as to form as an image in your imagination?), the idea of a math form following from axioms and a stable definition (as in the case of circle, square, cube, line, point, etc) can be taken as being there by virtue of the set method you have in mind, cause you can communicate it fully and already have the atomic parts of it defined as well (in juxtaposition to what i noted at in my reply to the first part of your comment in this post

* ).

-An Idea is in essence a category or type. In fact the original Platonic term is not "Idea", but "Eidos", which means "type" or "kind"/category. The ideas are any separate category/type you can think of. That pretty much includes any notion we have for anything, including all notions we have for examining notions we have, and so on, to endless iterations

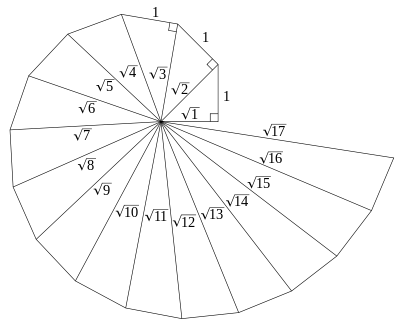

The argument by Plato/Socrates on Ideas boils down to the view (which i find correct, at least for the math i am familiar with and they talk about, but i already asked if any more modern math can be said to not flow from axioms as those older math did-- which i doubt is true) that math notions/ideas are formed in clearer and closer dependence on human sensory input, eg geometric notions seem to follow from humans having the ability to move in space, to observe things as integers, etc, while at the same time core math elements are abstractions that create antithesis in the overall system (eg Democritos, the one who theorised on 'atomic' final parts, had noted that the notion of 'single point' creates issues in geometry, since it functions as a sort of atom there but in a system which is not part of nature anyway. There is one paradox left by him, or rather a question, about whether a cone sectioned by a plane will have in two immediate outer points in that section an just above or below it, the same lenght or less/more, and it would follow that if it has less the cone is in reality step-by-step created in its atomic parts, while if it has the same length it would follow that it would remain the same even if we multiply that infinitesimal part, thus we would now have a cylinder instead of a cone).

Basically some notions in math are more tied to sensory or somatic input, others are more on the purely mental side of things (like the notion of Infinity, which the Eleatic philosophers (Parmenides, Zeno, etc) were so fond of using to argue that the senses and human perception in general is only a source of illusion and errror).

*(first part alluded to: ) There is a difference between inherent (ie perpetual by definition) abstraction, and complication, since the latter can (potentially) end at some point (eg if you can reach an atomic part of that which you aim to present/describe/define). In the case of 'abstract ideas' the argument is that there is no atomic end to an attempt to define a specific manifestation of them, so the idea itself is entirely abstract. The dialogue "Parmenides, or on Ideas" focused on the apparent inability to "know" something in the realm of the notionally but not axiomatically defined (ie that which you set as a subject to examine without itself following from axioms), due to the endless sub-parts one finds and thus cannot have a fully defined basis to stand on.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote