The Marian Reforms

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

With his election as Consul in 107 BC, and his subsequent appointment as commander of the Roman legions in Numidia, Marius faced a difficult challenge. Invasions of Germanic Cimbri and Teuton tribes into southern Gaul had forced large Roman armies to counter them. Thoroughly defeated in every engagement, Rome faced a manpower crisis similar to those faced during Hannibal's offensive in the Second Punic War. Prior to Marius, Rome recruited its main legionary force from the landowning citizen classes, men who could equip themselves and who supposedly had the most to lose in the case of Roman defeat.

Especially since the end of the Punic Wars and conquests in the east, the small landowning classes had dwindled to dangerous numbers. Wealthy senatorial aristocrats and equestrian elite land owners bought up small farms from struggling families and worked them with vast numbers of imported slaves. The jobless and landless mobs in Rome swelled out of control and led directly to the rise of the Gracchi, who championed political reform for the common citizens. By the time Marius came to power, the typical Roman recruiting base was literally non-existent. There simply weren't enough landowners available who weren't already fighting the Germanics or Jugurtha to field a new army.

Marius offered the disenfranchised masses permanent employment for pay as a professional army, and the opportunity to gain spoils on campaign along with retirement benefits, such as land. With little hope of gaining status in other ways, the masses flocked to join Marius in his new army. Besides gaining an army to confront the Germanic tribes, he also gained the loyalty of these men. The recruiting of the masses changed the entire relationship between citizens, generals, the Senate and Roman institutional ideology. Before Marius, armies fought for the survival or the expansion of the state, including their own lands, but after Marius, they fought for their Legate who gave them equipment and salaries, and who they came to like. With nowhere to return to in Rome or beyond, these new soldiers became career full-time professional soldiers, serving terms from 20 to 25 years. Now the Legates with their armies fought for their own glory. This extreme loyalty to the Legate led to rebellion and civil war as epitomised by Julius Caesar, who with his legions gained supreme power. Eventually this led to the crowning of the emperors.

Besides the social impact of Marius' decision, he made several major changes to legion structure and tactical formations. Most importantly, he mostly replaced the maniple structure which consisted of four distinct legionary units (though it did continue as a style of formation at least until the mid 1st century AD). Each used different weapons, served different purposes tactically and were arranged in varying sizes and formations, essentially based on the class of citizen they were recruited from. Each soldier in the pre-Marian system provided his own gear and armour, resulting in wide ranges in quality and completeness. Marius supplied his new army's gear partially through the resources of the state, and through his own vast wealth. In the future, most new recruits would be uniformly equipped through the state treasury or their recruiting general.

To replace the maniple as a formation, the cohort was adopted (though the formation had been used in moderation at least since the Punic Wars). Each soldier was equipped the same and assigned to one of six identical centuries of 80 men, making up the cohort unit. There were then 10 cohors of 480 men making up a legion, which standardized the entire system. The legion was made into a single large cohesive unit with interchangeable parts, capable of tactical flexibility not available with the complex structure of the Republican manipular system. The long single lines used prior to Marius were also eliminated in favour of a tiered 3 cohort deep battle line. This allowed rapid and easy support or rotating of fresh troops into combat.

Additionally, officers began to be recruited from within the ranks on a regular basis. While political appointments and promotions based on social or client status would still occur, this now allowed the common soldier a way of advancing based on merit. This improved the strength of the legion as a whole and instilled confidence in the soldiers, knowing their officers were capable leaders, not favoured clients of Senators in Rome. Marius, while adopting uniform gear for all, such as the gladius and scutum, also made significant changes to the common legionary spear (the pilum). It was made for the point to break off upon impact, making it ineffective to be thrown back by the enemy.

To eliminate another problem, the way the soldier's kit and baggage were carried was completely adjusted. From this point on, the legionary would carry their entire standard package including weapons, armour, food, tents, supplies and tools. The "Marius' Mules" allowed bulky, slow and cumbersome baggage trains to be shortened, making the infantry faster and more efficient. Finally, the legionary standards of the Eagle, wolf, minotaur, horse and boar were reduced to a single standard. The Eagle, representing Jupiter Optimus Maximus, replaced them all as the single symbol or loyalty, duty and pride among the soldiers.

Third Servile War

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

In 73 BC, one out of every three people living in Italy was a slave. Slaves were considered property, their life and death depended on their master. Only the strongest among them were trained as gladiators to fight and die in the roman arenas.

The Third Servile War (73-71 BC), also called the Gladiator War, was a rebellion of slaves, lead by Spartacus, Crixus and Oenomaus. In 73 BC, a group of 78 gladiators (according to Plutarch), managed to escape from the Capuan ludus of Lentulus Batiatus, eventually gathering a force of up to 120,000 supporters over the course of the rebellion. Little is known of Spartacus’ life prior to being captured and made a Gladiator. Even his Thracian origins are doubtful, as he was a Thraex Gladiator, so that the title "Thracian" may simply refer to the style of combat in which he was trained.

Rome dispatched a force of 3,000 ill trained militia, lead by the praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber, which was annihilated at Mount Vesuvius by the ingenuity of the Gladiators. A second expedition, under the praetor Publius Varinius, was then dispatched and defeated as well. With these successes, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, swelling their ranks to some 70,000 men in the winter of 73/72 BC.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The historians Plutarch and Appian left significantly different descriptions of what happened next:

According to Plutarch, in the spring of 72 BC, the slaves left their winter encampments and began to move northwards towards Cisalpine Gaul. The Senate, alarmed by the size of the revolt and the defeat of the praetorian armies of Glaber and Varinius, dispatched a pair of consular legions under the command of Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. Gellius engaged a group of about 30,000 slaves, under command of Crixus, and killed two-thirds of the rebels, including Crixus himself. However, Spartacus managed to defeat both Legions and continued his march north where he defeated yet another Roman army of some 10,000 soldiers, led by the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Gaius Cassius Longinus.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

At this point, the slave army could have crossed the Alps unhindered, thus reaching relative safety and escaping the influence of Rome.

The very successes of their army against Roman legions may have been their undoing. Spartacus wished to continue north to relative freedom from Roman interference, but victories, with the confidence and plunder they provided, had a powerful effect. Many of the Germanics and Gauls wished to stay in Italy and reap the rewards of their success. Rather than escape himself with a smaller army, Spartacus, either with visions of grandeur himself, or feeding off the power of a large force, next turned south. Some have suggested Rome itself was the target, but a rendezvous with Cilician pirates seems a more likely course. If they would not cross the Alps, his army may have been willing to cross to Sicily or even Africa as an alternative. Nevertheless, Spartacus and his army that had swelled to 120,000 men did move south. In the mountains near Thurii, they set up camp and gained much supply from local trade and plunder from raids. Equipping themselves into an appropriate military force, the slave army had grown from a minor nuisance to a formidable and legitimate power. The Senate, now facing this power, as it easily won victory after victory, looked to an experienced commander to deal with the threat. The current Consular commanders were withdrawn and the Propraetor Marcus Licinius Crassus was appointed to the special command. Crassus too command with 6 new legions and the four remaining veteran legions, making it quite apparent that Spartacus was considered a serious threat.

With M. Licinius Crassus in command, the tide was about to turn in the Romans favor. Initially, an over eager subordinate of Crassus led an attack on Spartacus that failed miserably.

In this defeat several Romans fled the battle in the face of the gladiator army. In order to put an end to the terrible performance of the legions against Spartacus, Crassus ordered the seldom used penalty of decimation as punishment.

In decimation, one of every ten men is beaten to death by their own fellow legionaries. While ancient reports are conflicting, at least one full cohort was subjected to decimation, or possibly his entire force. Whether those put to death numbered around 50 men or 4,000 is in dispute, but there was no question among legionaries that Crassus was not a man to accept defeat with grace.

Crassus then moved his entire body against a detached segment of Spartacus' forces. Crassus wiped out 10,000 of the rebel slaves commanded by Crixus, who had seperated from spartacus and the main army. Spartacus fled to Rhegium, across the straits from Sicily, with the hope of securing passage to the island, but was never able to secure passage with Cilician pirates.

Crassus pursued and built an extensive length of earthworks across the entire toe of Italy, trying to hem Spartacus in. At first Crassus was successful in trapping the slave army in, but the Senate viewed this as a demoralizing siege against an inferior foe. The great general Pompey was just returning from Spain, and they offered him an additional command to put an end to Spartacus once and for all.

Crassus was eager to achieve the victory himself and avoid sharing anything with his successful rival. He stepped up the pressure on Spartacus until he finally had little choice but to attempt a breakout. Unable to secure the passage to Sicily that he coveted, a breakout against the siege was ordered. While they did manage to escape, Spartacus lost a tenth of his army, or nearly 12,000 men. Free from Crassus' siege, Spartacus moved towards Brundisium, in the heel of Italy, where he still hoped to secure escape by sea.

The Romans were closing in, however, and an escape to Brundisium would never happen. Marcus Licinius Lucullus, fresh from a victory over Mithridates in the east, landed there with a full compliment of legionaries. Spartacus had little choice but to face his pursuers. Facing a full Roman army in open battle, especially one under adequate command, was something Spartacus tried to avoid, but in 71 BC, the slave army and the Romans met near Brundisium.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

In the battle the inspired Romans dominated the slaves, and they were cut down in huge numbers. By the end, Spartacus himself was wounded and likely killed (his body was never found). Crassus swept survivors and stragglers out of the surrounding countryside by the thousands, and prepared a horrific, if not intimidating punishment. Up to 6,000 rebellious slaves were spaced out along the Appian Way, from Rome to Capua. Here they were crucified and left to rot as a reminder to all future potentials rebellions. Pompey meanwhile had moved into Italy with his legions from Hispania. He swept out any remaining resistance and claimed final victory in the war. Pompey enjoyed a triumph for his 'victory' in Hispania, while Crassus was given the lesser honor of an ovation for his victory over mere slaves. The incident was an additional thorn in the side of a growing rivalry between Crassus and Pompey.

As the rivals stood on Rome's door step with full armies, both were elected Consul for 70 BC, despite Pompey's youth and lack of previous offices. Despite their rivalry, both men seemingly worked well enough together to repeal many of Sulla's unpopular laws. Pompey would soon be commissioned for further exploits in the east while Crassus would remain in Rome to continue amassing his fortune and influencing the politics of the 60's BC.

Gaius Julius Caesar

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Gaius Julius Caesar was born most likely on July (originally Quinctilis, but renamed by Caesar in his own calendar reform) 13, 100 BC. Caesar was a member of the deeply patrician Julii family with roots dating to the foundation of the city itself. He later claimed to be a direct descendent of Aenaes, son of Venus, and therefore related to the gods themselves.

Still, at his start, the Caesar family was an impoverished line of the noble original clans. No Caesars in recent generations had held the seat of Consul but while still highly respected, they held little political clout. His father, Gaius Julius as well, had served in a respectable capacity within the Senate, but had little notoriety aside from his son's legacy. His mother, Aurelia, of the Aurelii Cotta line, seems to have been both a remarkable woman and a major impact on the life of her son.

Caesar was raised in the common quarters of Rome, or the Subura among the lower citizen classes. His home was what functioned as an apartment building in the modern world, or what was known as an insula. Even for a patrician family in poor financial straits, this was a definite handicap for future political ambition. However, the young Caesar certainly learned a great deal from his experiences as a child, as he early on realized the power in championing the common man. It wouldn't take a genius to understand that several politicians in this era made a name for themselves using this method, and Caesar certainly caught on to this easily. He had, though, the added advantage of his patrician heritage along with a sort of political genius that would push him to the very limit of Roman power.

Two major events impacted the life of the young Caesar. The later and seemingly less momentous event of the two was the death of his father at the age of 15 in 85 BC. So few of the details of Gaius Julius Caesar the elder's life are known, that it's difficult to determine the impact this may have had. While he certainly played a role in the life of his young son, he was often away on military and Senatorial obligations, as was often the case with Patrician families. His father had reached the office of Praetor prior to his death, the office just below Consul, and at least helped set the stage for the Caesar line to return to the highest order.

The more significant event in the life of Caesar was a marriage arrangement that would have enormous impact on Roman culture as a whole. The marriage of his aunt Julia to the novus homo (new man) Gaius Marius had repercussions that affected the entire ancient world. Through this marriage in 110 BC and 10 years prior to the birth of his famous nephew, Marius gained the political and familial connection necessary to advance his own career up the cursus honorum. While it may have been frowned upon by the elite of the day, first off in giving the uncouth Marius such assistance, it was a completely understandable move by the Caesars. Marius was certainly one of the richest men in Rome of the time and while he gained political clout, the Caesar family gained the wealth required to finance election campaigns for Caesar's father and uncles. As previously suggested his father attained the rank of Praetor and his uncle, Lucius Julius Caesar rose to a prominent Consulship during the Social War of 90 to 87 BC.

Marius' impact on the future dictator must have been immense. Their careers follow notable similarities that certainly show a profound influence by the uncle on the nephew. More importantly, however, Caesar had the great fortune of his patrician background which gave huge advantages over Marius. He also was able to play witness to both the successes and failures and adjust his own plans for the future accordingly. Marius was the pre-eminent Roman just prior to Caesar's birth, serving 6 Consulships, winning the war against Jugurtha, reforming the legions and the social order, and saving Rome from the Germanic Cimbri and Teutone threat. By the time Caesar was a young man, however, Marius had fallen deeply out of favor, though he was still a player of some note. As Caesar began his own career, he would be thrust into the coming conflicts between Marius and his rival Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The advancement of Caesar in light of the turmoil of the day is notable enough, the fact that he even survived may be even more remarkable.

Three candidates stood for the consulship: Caesar, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, who had been aedile with Caesar several years earlier, and Lucius Lucceius. The election was dirty. Caesar canvassed Cicero for support, and made an alliance with the wealthy Lucceius, but the establishment threw its financial weight behind the conservative Bibulus, and even Cato, with his reputation for incorruptibility, is said to have resorted to bribery in his favour. Caesar and Bibulus were elected as consuls for 59 BC.

Caesar was already in Crassus's political debt, but he also made overtures to Pompey, who was unsuccessfully fighting the Senate for ratification of his eastern settlements and farmland for his veterans. Pompey and Crassus had been at odds since they were consuls together in 70 BC, and Caesar knew if he allied himself with one he would lose the support of the other, so he endeavoured to reconcile them. Between the three of them, they had enough money and political influence to control public business. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate (rule of three men), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter Julia. Caesar also married again, this time Calpurnia, daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, who was elected to the consulship for the following year.

Caesar proposed a law for the redistribution of public lands to the poor, a proposal supported by Pompey, by force of arms if need be, and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, and the triumvirate's opponents were intimidated. Bibulus attempted to declare the omens unfavourable and thus void the new law, but was driven from the forum by Caesar's armed supporters. His lictors had their fasces broken, two tribunes accompanying him were wounded, and Bibulus himself had a bucket of excrement thrown over him. In fear of his life, he retired to his house for the rest of the year, issuing occasional proclamations of bad omens. These attempts to obstruct Caesar's legislation proved ineffective. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as "the consulship of Julius and Caesar".

This also gave rise to this lampoon-

The event occurred, as I recall, when Caesar governed Rome-

Caesar, not Bibulus, who kept his seat at home.

When Caesar and Bibulus were first elected, the aristocracy tried to limit Caesar's future power by allotting the woods and pastures of Italy, rather than governorship of a province, as their proconsular duties after their year of office was over. With the help of Piso and Pompey, Caesar later had this overturned, and was instead appointed to govern Cisalpine Gaul(northern Italy) and Illyricum (the western Balkans), with Transalpine Gaul (southern France) later added, giving him command of four legions. The term of his proconsulship, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the usual one. When his consulship ended, Caesar narrowly avoided prosecution for the irregularities of his year in office, and quickly left for his province.

Caesar was still deeply in debt, and there was money to be made as a provincial governor, whether by extortion or by military adventurism. Caesar had four legions under his command, two of his provinces, Illyricum and Gallia Narbonensis, bordered on unconquered territory, and independent Gaul was known to be unstable. Rome's allies the Aedui had been defeated by their Gallic rivals, with the help of a contingent of Germanic Suebi under Ariovistus, who had settled in conquered Aeduan land, and the Helvetii were mobilising for a mass migration, which the Romans feared had warlike intent.

The Gallic Wars

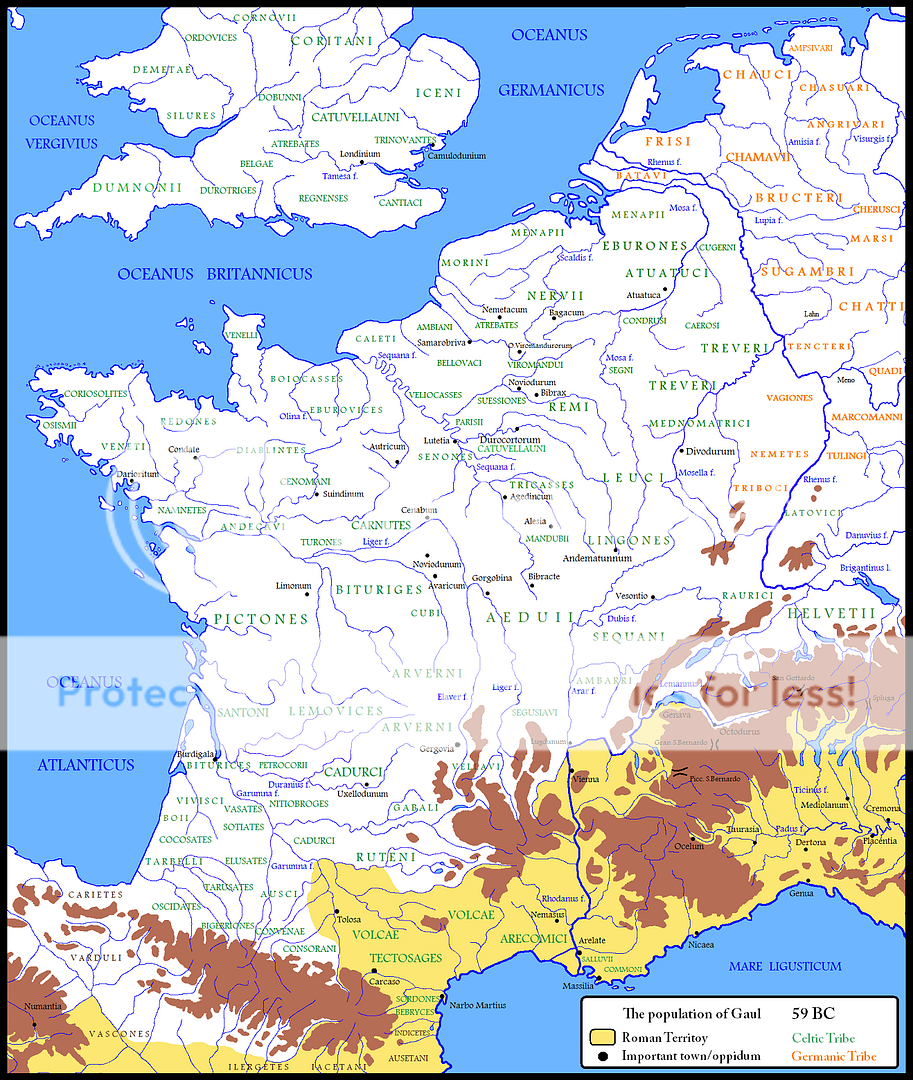

The Gallic Wars were a series of military campaigns waged by the Roman proconsul Julius Caesar against several Gallic tribes, lasting from 58 BC to 51 BC. The Gallic Wars culminated in the decisive Battle of Alesia in 52 BC, in which a complete Roman victory resulted in the expansion of the Roman Republic over the whole of Gaul. In 58 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar ended his consulship in Rome, and was heavily indebted. However, being a member of the First Triumvirate, he had secured for himself the governorship of three provinces, Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul and Illyricum. Under his direct command Caesar had initially four veteran legions: Legio VII, Legio VIII, Legio IX Hispana, and Legio X. Caesar also had the legal authority to levy additional legions and auxiliary units as he saw fit.

His ambition was clearly to conquer and to plunder some territories but it is likely that Gaul was not his initial target. It is very likely that he was planning a campaign against the kingdom of Dacia.

The numerous Gaulish tribes, already influenced by the Roman culture, were totally divided at this time. Some of them, e.g. the Aedui, had allied with Rome. In 109 BC, only fifty years before, Italy had been invaded, and saved only after several bloody and costly battles by Gaius Marius.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Battle of Bibracte

The Helvetii were forced to abandon their homelands in modern day Switzerland due to the expansion of the Suebi, a Germanic tribe lead by Ariovistus. They planned to settle in Gaul and wanted to cross the Roman province Gallia Narbonensis in order to reach it. Caesar, hoping to incite a conflict, denied their request and build a wall between the Jura Mountains and Lake Geneva. Subsequently, the Helvetii averted aggravating Caesar and avoided Roman territory. Nonetheless, Caesar levied two additional legions and pursued them, eventually leading to the Battle of Bibracte.

The battle was fought between the Helvetii and six roman legions including auxiliaries, June 58 BC. The Helvetii and their allies (Boii, Tulingi and Rauraci) were lead by Divico who commanded approximately 90,000 warriors. Caeser and his six legions (VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII) numbered around 30,000. On June 20th, the Helvetii turned and attacked Caesar who formed his legions in a defensive position near Montmort, 22km south of Bibracte. Caesar formed his veteran legions (VII, VIII, IX, X) in three rows in order to repel the oncoming attack. Legions XI and XII, as well as the auxiliaries, acted as reserve. First the roman cavalry attacked, but was driven back since the Helvetii had formed a shield wall and now advanced towards the roman lines. Once they closed in at about 10 to 15 yards, the legionaries threw their pila, breaking the enemy shield wall and driving the Helvetii back about 1.5km. Finally the Boii and Tulingi reached the battlefield and flanked the roman army with some 15,000 men. Seeing this, the Helvetii counterattacked the roman main line from which Caesar had to remove the 3rd row in order to form a new defensive position against the Boii and Tulingi. Eventually the Helvetii and their allies broke and had to retreat.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

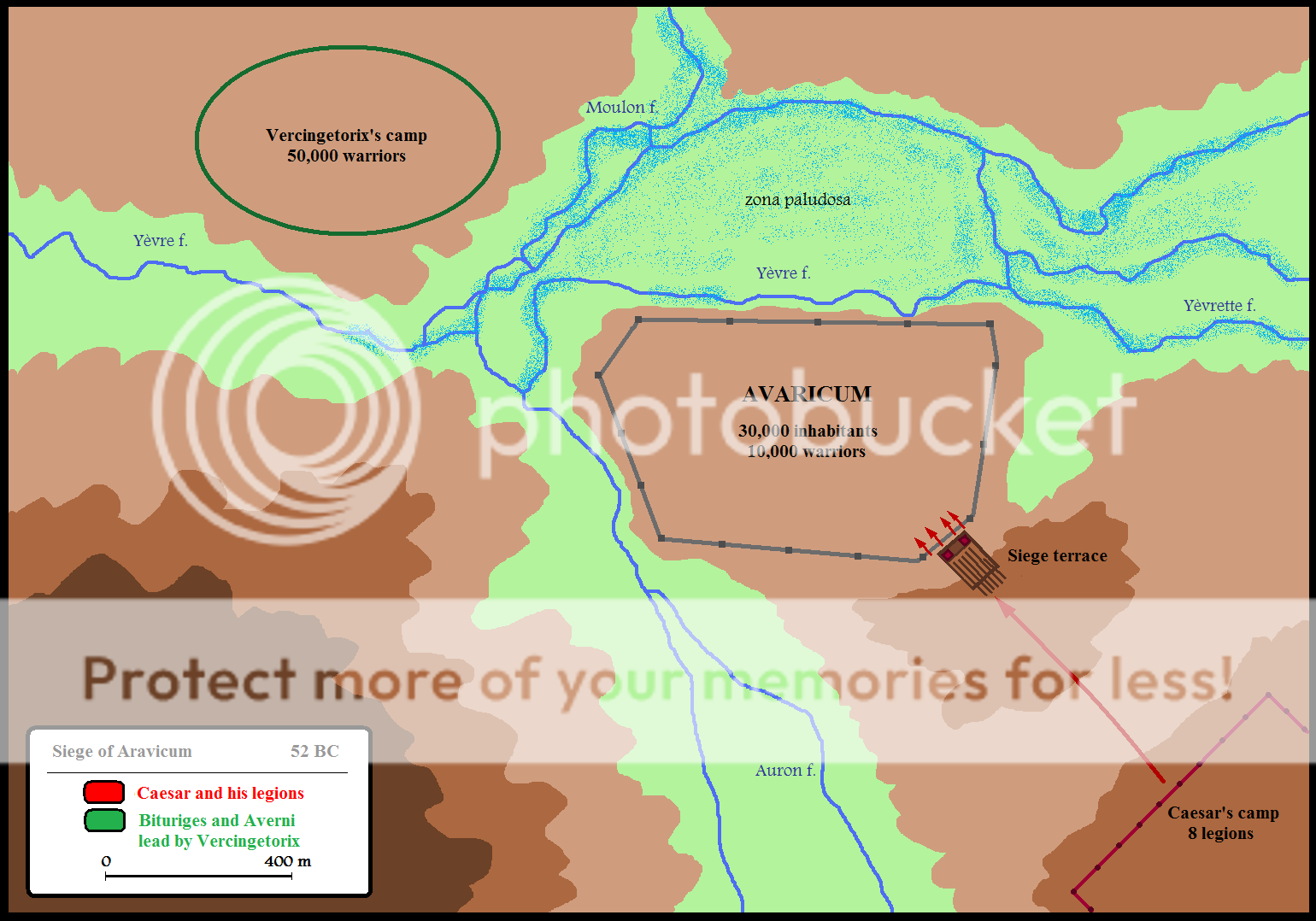

Siege of Avaricum

The year is 52 BC. Caesar had already won many great victories over the Gauls. Now he set his eyes on Avaricum, the biggest and best fortified town of the Biturges. Vercingetorix, son of Celtillus, who started the Great Gallic Revolt, was confident he could protect the town from the romans. Avaricum was easy to defend as it was protected by a river and a sizeable marsh, allowing only a narrow approach towards the town. Caesar ordered the construction of siege towers and ramps.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Vercingetorix, who had 50,000 warriors in his camp outside of the town, continuously harassed the romans and tried to sabotage work on their siege equipment. The Romans eventually ran low on supplies due to vercingetorix's raids and also because allied tribes, e.g. the Aeudi, were reluctant to supply them. The Gauls had become much more skilled at defending their towns against Roman siege engines, and many of the inhabitants of Avaricum were experienced iron miners, which gave them the skills needed to counter the Roman mound. When the Romans tried to use grappling hooks to pull stones off the walls the Gauls trapped them and used their own machines to drag the grappling hooks inside the city. When the Romans attempted to dig tunnels under the walls the Gallic miners dug their own countermines.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

On the next day, under the cover of a storm, the Romans successfully reached the top of the town walls. The fall of the Avaricum was followed by a massacre of the inhabitants, woman and children included. Caesar described this as having been caused by a combination of anger at the massacre of the Romans at Cenabum and frustration after the long difficult siege, but his brief description gives no indication of his attitude to this massacre. Merely 800 Gauls survived the slaughter. The siege lasted for twenty seven days.

The fall of Avaricum didn't have the effect Caesar had hoped. Vercingetorix managed to restore the morale of his army with a rousing speech, and he was soon able to replace the troops lost during the siege. More importantly the Aedui finally abandoned their long attachment to the Roman cause and joined the revolt. Caesar lost one of his best sources of cavalry, and faced an ever more powerful coalition of Gallic tribes. His next move, an attack on Gergovia, ended with his only major defeat at the hands of the Gauls, but Vercingetorix then attempted to defend Alesia, a move that gave Caesar a chance to defeat the Gallic army in a single location.

Battle of Gergovia

The fall of Avaricum came at the end of the winter of 53-52 B.C. and the improving weather convinced Caesar that he could risk a wider campaign. He split his army of ten legions in half. Four, under his most able lieutenant Labienus, were sent north into the lands of the Senones and Parisii, who at that point were the most northerly tribes to have rebelled. Caesar himself led the remaining six legions south to attack Gergovia, in the lands of the Arverni, Vercingetorix's own tribe.

Gergovia itself was built in a strong position on a steep hill. On his arrival Caesar realised that he wouldn't be able to storm the city, and decided to prepare for a regular siege. Initially all six legions camped together, but after a few days Caesar decided to capture a small hill that he hoped would limit the defender's access to fresh water. Two legions were posted in a small camp on this hill, with the remaining four legions in the main camp on the plains. He ordered a double trench, 12 feet wide, to be constructed between a captured hill and his main camp. Intending to completely encircle Gergovia and starve the Gauls inside, Caesar was interrupted by betrayal from his Gallic allies the Aedui, led by Litaviccus whom he fought and defeated after a desperate struggle.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Caesar then went back to Gergovia and realised that his siege would fail. His only chance now of victory was to get Vercingetorix off the high ground. He used a legion as a decoy and moved onto better ground, capturing three Gallic camps in the process. He then ordered a general retreat to fool Vercingetorix and pull him off the high ground. However, the retreat was not heard by most of Caesar's force. Instead, spurred on by the ease with which they captured the camps, they pressed on toward the town and mounted a direct assault on it. The noise of the assault drew Vercingetorix back into the town. 46 centurions and 700 legionaries died in the resulting engagement, and over 6,000 were wounded on the Roman side, compared to the several hundred Gauls killed and wounded. In the wake of the battle, Caesar lifted his siege and advanced instead into Aedui territory.

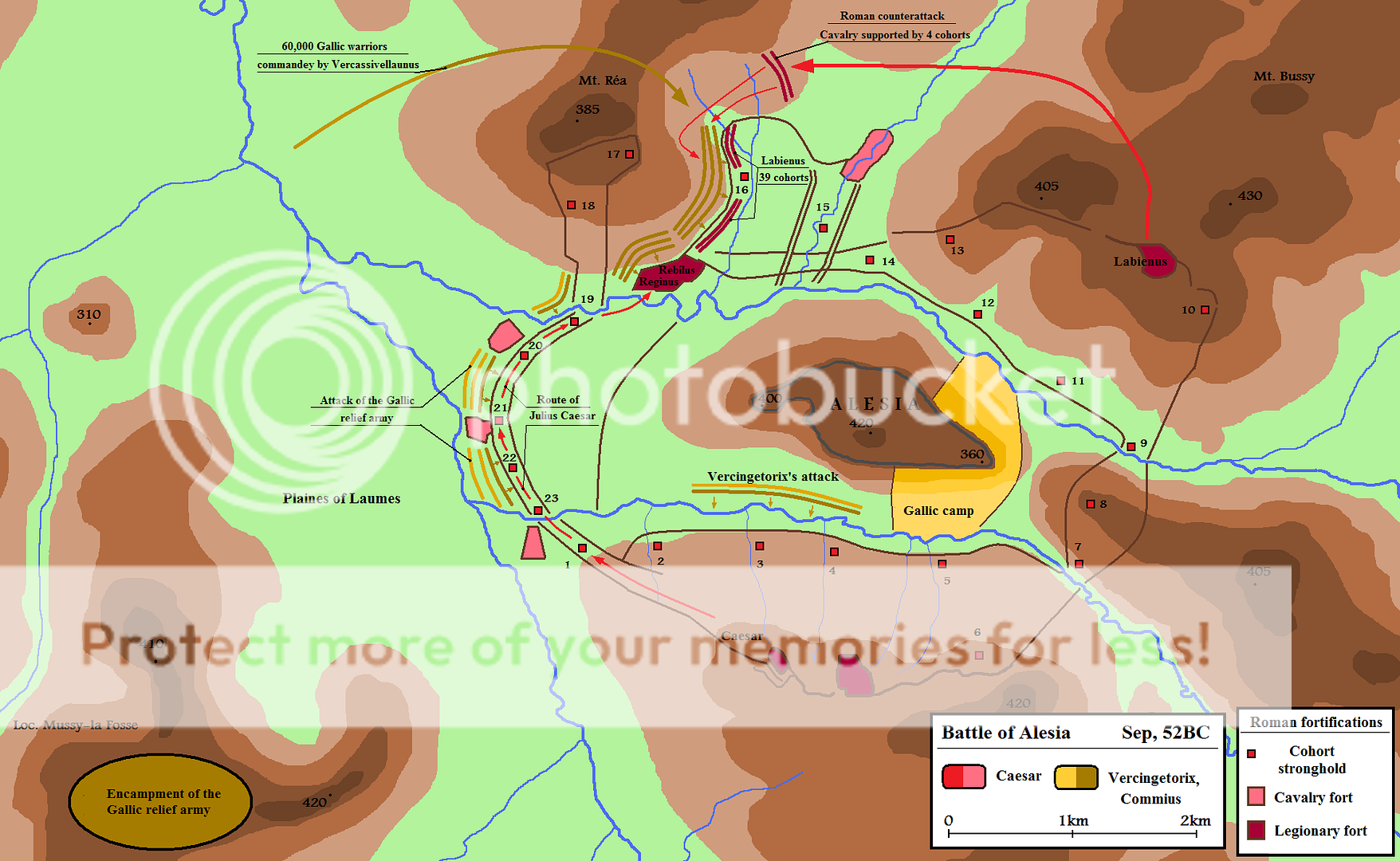

Battle of Alesia

Situated on a hill and surrounded by river valleys, Alesia offered a strong defensive position. Arriving with his army, Caesar declined to launch a frontal assault and instead decided to lay siege to the town. As the entirety of Vercingetorix's army was within the walls along with the town's population, Caesar expected the siege to be brief. To ensure that Alesia was fully cut off from aid, he ordered his men to construct and encircling set of fortifications known as a circumvallation. Featuring an elaborate set of walls, ditches, watchtowers, and traps, the circumvallation ran approximately eleven miles.

Understanding Caesar's intentions, Vercingetorix launched several cavalry attacks with the goal of preventing completion of the circumvallation. These were largely beaten off though a small force of Gallic cavalry was able to escape. The fortifications were completed in around three weeks. Concerned that the escaped cavalry would return with a relief army, Caesar began construction on a second set of works which faced out. Known as a contravallation, this thirteen-mile fortification was identical in design to the inner ring facing Alesia.

Occupying the space between the walls, Caesar hoped to end the siege before aid could arrive. Within Alesia, conditions quickly deteriorated as food became scarce. Hoping to alleviate the crisis, the Mandubii sent out their women and children with the hope that Caesar would open his lines and allow them to leave. Such a breach would also allow for an attempt by the army to break out. Caesar refused and the women and children were left in limbo between his walls and those of the town. Lacking food, they began to starve further lowering the morale of the town's defenders.

In late September, Vercingetorix faced a crisis with supplies nearly exhausted and part of his army debating surrender. His cause was soon bolstered by the arrival of a relief army under the command of Commius. On September 30, Commius launched an assault on Caesar's outer walls while Vercingetorix attacked from the inside. Both efforts were defeated as the Romans held. The next day the Gauls attacked again, this time under the cover of darkness. While Commius was able to breach the Roman lines, the gap was soon closed by cavalry led by Mark Antony and Gaius Trebonius.

On the inside, Vercingetorix also attacked but the element of surprise was lost due to the need to fill in Roman trenches before moving forward. As a result, the assault was defeated. Beaten in their early efforts, the Gauls planned a third strike for October 2 against a weak point in Caesar's lines where natural obstacles had prevented construction of a continuous wall. Moving forward, 60,000 men led by Vercassivellaunus struck the weak point while Vercingetorix pressured the entire inner line.

Issuing orders to simply hold the line, Caesar rode through his men to inspire them. Breaking through, Vercassivellaunus' men pressed the Romans. Under extreme pressure on all fronts, Caesar shifted troops to deal with threats as they emerged. Dispatching Labienus' cavalry to help seal the breach, Caesar led a number of counterattacks against Vercingetorix's troops along the inner wall. Though this area was holding, Labienus' men were reaching a breaking point. Rallying thirteen cohorts (approx. 6,000 men), Caesar personally led them out of the Roman lines to attack the Gallic rear.

Spurred on by their leader's personal bravery, Labienus' men held as Caesar attacked. Caught between two forces, the Gauls soon broke and began fleeing. Pursued by the Romans, they were cut down in large numbers. With the relief army routed and his own men unable to break out, Vercingetorix surrendered the next day and presented his arms to the victorious Caesar.

As with most battles from this period, precise casualties are not known and many contemporary sources inflate the numbers for political purposes. With that in mind, Romans losses were around 12,800 killed and wounded, while the Gauls may have suffered up to 250,000 killed and wounded as well as 40,000 captured. The victory at Alesia effectively ended organized resistance to Roman rule in Gaul. A great personal success for Caesar, the Roman Senate declared twenty days of thanksgiving for the victory but refused him the a triumphal parade through Rome. As a result, political tensions in Rome continued to build which ultimately led to a civil war.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The pre–Civil War politico–military situation

Caesar’s Civil War resulted from the long political subversion of the Roman Government’s institutions, begun with the career of Tiberius Gracchus, continuing with the Marian reforms of the legions, the bloody dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and completed by the First Triumvirate over Rome.

The First Triumvirate (so denominated by Cicero), comprising Julius Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey, ascended to power with Caesar’s election as consul, in 59 BC. The First Triumvirate was unofficial, a political alliance the substance of which was Pompey’s military might, Caesar’s political influence, and Crassus’s money. The alliance was further consolidated by Pompey’s marriage to Julia, daughter of Caesar, in 59 BC. At the conclusion of Caesar’s first consulship, the Senate, rather than granting him a provincial governorship -- tasked him with watching over the Roman forests; this job, specially-created by his Senate enemies, was meant to occupy him without giving him command of armies, or garnering him wealth and fame. Caesar, with the help of Pompey and Crassus, evaded the Senate's decrees by legislation passed through the popular assemblies. By these acts, Caesar was promoted to Roman Governor of Illyricum and Cisalpine Gaul. Transalpine Gaul (southern France) was added later. The various governorships gave Caesar command of an army of four legions. The term of his proconsulship, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the customary one year.

In 52 BC, at the First Triumvirate’s end, the Roman Senate supported Pompey as sole consul; meanwhile, Caesar had become a military hero and champion of the people. Knowing he hoped to become consul when his governorship expired, the Senate, politically fearful of him, ordered he resign command of his army. In December of 50 BC, Caesar wrote to the Senate agreeing to resign his military command if Pompey followed suit. Offended, the Senate demanded he immediately disband his army, or be declared an enemy of the people — an illegal political bill, for he was entitled to keep his army until his term expired. A secondary reason for Caesar’s immediate want for another consulship was delaying the inevitable senatorial prosecutions awaiting him upon retirement as governor of Illyricum and Gaul; said potential prosecutions were based upon alleged irregularities occurred in his consulship, and war crimes committed in his Gallic campaigns. Moreover, Caesar loyalists, the tribunes Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) and Quintus Cassius Longinus, vetoed the bill, and were quickly expelled from the Senate. They then joined Caesar, who had assembled his army, whom he asked for military support against the Senate; agreeing, his army called for action.

In 50 BC, at his Proconsular term’s expiry, the Pompey-led Senate ordered Caesar’s return to Rome and the disbanding of his army, and forbade his standing for election in absentia for a second consulship; because of that, Caesar thought he would be prosecuted and rendered politically marginal if he entered Rome without consular immunity or his army — to wit, Pompey accused him of insubordination and treason.

The Great Roman Civil War

Crossing the Rubicon

On 10 January 49 BC, leading one legion, the Legio XIII Gemina, General Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, the boundary between the Cisalpine Gaul province, to the north, and Italy proper, to the south, a legally-proscribed action forbidden to any army-leading general. The proscription protected the Roman Republic from a coup d'état (internal military threat); thus, Caesar's military action began a civil war. This act of war on the Roman Republic by Caesar led to widespread disapproval amongst the Roman civilians, who believed him a traitor. The historical record differs about which decisive comment Caesar made on crossing the Rubicon — one report is Alea iacta est (usually translated as "The die is cast").

The March on Rome and the early Hispanian campaign

Caesar’s March on Rome was a triumphal progress; yet, the Senate, ignorant of Caesar’s being armed only with a single legion, feared the worst and supported Pompey, who, on grasping the Republic’s endangerment, said: “Rome cannot be defended”, and escaped to Capua — with his politicians, the aristocratic Optimates and the regnant consuls; Cicero later characterised Pompey’s “outward sign of weakness” as allowing Caesar’s politico-military consolidation to achieve Roman dictatorship.

Despite having retreated, at his central-Italian bivouac, Pompey was armed with two legions, some 11,500 soldiers (he earlier had ordered Caesar return to Italy from Gaul), and some hastily-levied Italian troops commanded by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (Domitius). As Caesar progressed southwards, so Pompey retreated southwards, to Brundisium, from whence he repeatedly ordered Domitius north to combat and stop Caesar’s Roman march (then south-bound, along the eastern coast); his inaction — repeated refusal of Pompey’s combat orders — gave Caesar the initiative to attack and defeat Domitius’s Pompeian armies in bivouac. In the event, Pompey escaped to Brundisium, there awaiting sea transport for his legions, to Epirus, in the Republic’s eastern Greek provinces — expecting his influence to yield money and armies for a maritime blockade of Italy proper. Meanwhile, the aristocrats (the Optimates) — including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger — joined Pompey there, whilst leaving a rear guard at Capua.

Caesar pursued Pompey to Brundisium, expecting restoration of their alliance of ten years prior; to wit, throughout the Great Roman Civil War’s early stages, Caesar frequently proposed to Pompey that they, both generals, sheathe their swords. Pompey refused, legalistically arguing that Caesar was his subordinate and thus was obligated to cease campaigning and dismiss his armies before any negotiation. As Consul of Rome, Pompey commanded legitimacy, whereas Caesar’s military crossing of the Rubicon River frontier de jure rendered him a de facto enemy of the Senate and People of Rome. Nevertheless, in March of 49 BC, Pompey escaped Caesar at Brundisium, fleeing by sea to Epirus, in Roman Greece.

Advantaging himself of Pompey’s absence from the Italian mainland, Caesar effected an astonishingly fast 27-day, north-bound forced march to destroy, in the Battle of Ilerda, Hispania’s politically leader-less Pompeian army, commanded by the legates, Lucius Afranius (Afranius) and Marcus Petreius (Petreius), afterwards pacifying Hispanic Rome; in campaign, the Caesarian forces — six legions, 3,000 cavalry (Gallic campaign veterans), and Caesar’s 900-horse personal bodyguard — suffered 700 men killed in action, while the Pompeian forces lost 200 men killed and 600 wounded. Returned to Rome in December of 49 BC, Caesar was dictator for eleven days, tenure sufficient to win him Consular election, afterwards, he renewed pursuit of Pompey, then in Roman Greece.

The Greek and African campaigns

At Brundisium, Caesar assembled an army of some 15,000 soldiers, and crossed the strait of Otranto to Epirus, in Greece. In that time, Pompey considered three courses of action: (i) alliance with the King of Parthia, an erstwhile ally, far to the east; (ii) invade Italy with his naval superiority; and (iii) confronting Julius Caesar in decisive battle. A Parthian alliance was unfeasible, a Roman general fighting Roman legions with foreign troops was craven; and the military risk of an Italian invasion was politically unsavoury, because, the Italians (who thirty years earlier had rebelled against Rome) might rise against him; thus, on councilor’s advice, Pompey decided to fight Julius Caesar in decisive battle.

Moreover, Caesar’s pursuing him to Illyrium, across the Adriatic Sea, decided the matter, and, on 10 July 48 BC, Pompey fought him in the Battle of Dyrrhachium, costing Caesar 1,000 veteran legionnaires and a retreat. Disbelieving that his army had bested Caesar’s legions, Pompey misinterpreted the retreat as a feint to a trap, and refused to give chase for the decisive, definitive coup de grâce — thus losing the initiative, and the chance to quickly conclude Caesar’s Civil War; meanwhile, Caesar retreated southwards. Near Pharsalus, Caesar pitched a strategic bivouac, and Pompey attacked, yet, despite his much larger army, was conclusively defeated by Caesar's troops. A major reason for Pompey's defeat was a miscommunication among front cavalry horsemen.

The Egyptian dynastic struggle

Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by an officer of King Ptolemy XIII. In Rome in the meantime, Caesar was appointed dictator, with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse; Caesar resigned this dictatorate after eleven days and was elected to a second term as consul with Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus as his colleague. He pursued the Pompeian army to Alexandria, where they camped and became involved with the Alexandrine civil war between Ptolemy and his sister, wife, and co-regnant queen, the Pharaoh Cleopatra VII. Perhaps as a result of Ptolemy's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra; he is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey's head, which was offered to him by Ptolemy's chamberlain Pothinus as a gift. In any event, Caesar defeated the Ptolemaic forces and installed Cleopatra as ruler, with whom he fathered his only known biological son, Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as "Caesarion". Caesar and Cleopatra never married, due to Roman law that prohibited a marriage with a non-Roman citizen.

The war against Pharnaces

After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, he went to Syria, and then to Pontus to deal with Pharnaces II, a client king of Pompey's who had taken advantage of the Romans being distracted by their civil war to oppose the Roman-friendly Deiotarus and make himself the ruler of Colchis and lesser Armenia. At Nicopolis he had defeated what little Roman opposition Caesar's Asian lieutenant Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus could muster. He had also taken the city of Amisus, which was a Roman ally, made all the boys eunuchs and sold the inhabitants to slave traders. After this show of strength against the Romans, Pharnaces drew back to suppress revolt in his new conquests.

Nevertheless, the extremely rapid approach of Caesar in person forced Pharnaces to turn his attention back to the Romans. At first, recognizing the threat, he made offers of submission, with the sole object of gaining time until Caesar's attention fell elsewhere; Caesar's speed brought war quickly and battle took place near Zela (modern Zile in Turkey), where Pharnaces was routed with just a small detachment of cavalry. Caesar's victory was so swift and complete that, in a letter to a friend in Rome, he famously said of the short war, “Veni, vidi, vici” (“I came, I saw, I conquered”) – indeed, for his Pontic triumph, that may well have been the label displayed above the spoils.

Pharnaces himself fled quickly back to the Bosporus, where he managed to assemble a small force of Scythian and Sarmatian troops, with which he was able to gain control of a few cities; however, a former governor of his, Asandar, attacked his forces and killed him. The historian Appian states that Pharnaces died in battle; Dio Cassius says Pharnaces was captured and then killed.

The later campaign in Africa: the war on Cato

Caesar returned to Rome to deal with several mutinous legions. While Caesar had been in Egypt installing Cleopatra as Queen, four of his veteran legions encamped outside of Rome under the command of Mark Antony. The legions were waiting for their discharges and the bonus pay Caesar had promised them before the battle of Pharsalus. As Caesar lingered in Egypt, the situation quickly deteriorated. Antony lost control of the troops and they began looting estates south of the capital. Several delegations of diplomats were dispatched to try to quell the mutiny. Nothing worked and the mutineers continued to call for their discharges and back pay. After several months, Caesar finally arrived to address the legions in person. Caesar knew he needed these legions to deal with Pompey's supporters in north Africa, who had mustered 14 legions of their own. Caesar also knew that he did not have the funds to give the soldiers their back pay, much less the money needed to induce them to reenlist for the north African campaign.

When Caesar approached the speaker's dais, a hush fell over the mutinous soldiers. Most were embarrassed by their role in the mutiny in Caesar's presence. Caesar asked the troops what they wanted with his cold voice. Ashamed to demand money, the men began to call out for their discharge. Caesar bluntly addressed them as "citizens" instead of "soldiers," a tacit indication that they had already discharged themselves by virtue of their disloyalty. He went on to tell them that that they would all be discharged immediately. He said he would pay them the money he owed them after he won the north African campaign with other legions. The soldiers were shocked. They had been through 15 years of war with Caesar and they had become fiercely loyal to him in the process. It had never occurred to them that Caesar did not need them. The soldiers' resistance collapsed. They crowded the dais and begged to be taken to north Africa. Caesar feigned indignation and then allowed himself to be won over. When he announced that he would suffer to bring them along, a huge cheer arose from the assembled troops. Through a brilliant combination of personal charisma and reverse psychology, Caesar reenlisted four enthusiastic veteran legions to invade north Africa without spending a single sesterce.

In the same year he set out for Africa, where the followers of Pompey had fled, to end their opposition led by Cato.

Caesar quickly gained a significant victory at Thapsus in 46 BC over the forces of Metellus Scipio (who was drowned) and Cato the Younger and Juba (who both committed suicide).

The second Hispanic campaign: end of the Caesar’s Civil War

Nevertheless, Pompey's sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus (Caesar's former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore) and second in command in the Gallic War) escaped to Hispania. Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Munda in March 45 BC. During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) and 45 BC (without colleague).

Octavian

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Early Years

Gaius Octavius was born on September 23, 63 BC, and though of distant relation to Caesar, his eventual rise to prominence was unexpected. He was the son of a 'new man' bearing the same name from Velitrae in Latium. His father had reached the rank of praetor before dying when Octavian was a boy of only 4 years old, just as Caesar was launching his war in Gaul. His father was married to Atia, the daughter of a somewhat obscure Senator, M. Atius Balbus and Julia, sister of Julius Caesar, making him the great nephew of the dictator. There were other first nephews, but Caesar didn't seem to hold them in as high regard as the young Octavian, though one, Q. Pedius, did serve Caesar as a legate. Despite his relation to Caesar, there was some questionable lineage throughout his family.

Later opponents, Marc Antony included, attacked his heritage by claiming his ancestors were freedmen and moneychangers, not the sort of lineage that one might expect from a rising star in Roman politics. Suetonius claims that Octavian carried another surname as a youth, Thurinus. This, Suetonius claims, either represented Octavian's historical familial roots, or the place where his father bested remnants of slave armies while he served as governor of Macedonia. Suetonius even reports that he came into a statue of Octavian as a boy bearing the inscription Thurinus, which he promptly gifted to the Emperor Hadrian, who prized it highly. Whatever the case, some evidence suggests that opponents like Antony may have used this surname against Octavian.

At the age of twelve (51 BC), Octavian's grandmother and sister of Caesar, died, ushering him into his first major public appearance. He delivered her eulogy, and like many other young political hopefuls, this was the first opportunity to make a mark on both the aristocracy and the common masses alike. While young Octavian was certainly noticed by Caesar at some point, evidence of direct involvement is conflicting. Octavian was coming into adulthood just as Caesar was embroiled in Gaul and in the Civil War that followed, and there certainly wouldn't have been much time for camaraderie. With Octavian's age, and reports of sickliness as a child, contact must have been limited. This, however, didn't stop Caesar from having an impact on the young man's career. In 48 BC, Octavius was appointed as a pontiff (priest) at the tender age of 15. It's possible the Caesar planned to take his protégé with him to Africa to face of against the Republicans there, but either sickness, or an over protective mother shot down this idea.

In 46 BC, Octavian took part in Caesar's triumphal parades in Rome, earning himself some military award, despite taking no part in the effort. Clearly this shows that Caesar at least had some design on his great nephew's future. The following year Octavian followed Caesar to Spain, where the dictator conducted the last battle of his career against the sons of Pompey at Munda. Though Octavian himself took little part in the actual military aspect of this campaign, his journey to join Caesar seems a significant development in the relationship. While en route, Octavian was faced with difficulties in avoiding enemy resistance, including a shipwreck which could've been disastrous. When the two finally crossed paths, Caesar was apparently very pleased with his nephew's daring determination and courage. Other than Caesar's short triumphal visit to Rome, this period in Spain was likely the first time the two were truly able to foster a serious relationship. If at any time, this was the chance for Octavian to impress Caesar, and for Caesar to bring the young man under his wing. While there is little historical documentation, Octavian likely learned a great deal about provincial administration, warfare and political manipulation while a part of his uncle's entourage. Nicolaus of Damascus, though his account is unreliable at best, indicates that Octavian was so firmly entrenched with Caesar that he was able to have considerable influence. In one example, Nicolaus states that Octavian begged a pardon for the brother of his great boyhood friend, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, who had served under Cato in Africa. Despite beginning to retract on the number of pardons issued by this time in the civil war (as many who were pardoned would continue to fight), Caesar relented, and may have helped cement a lifetime friendship with the two future leaders of Rome.

By the end of the campaign in Spain, Octavian was sent to Apollonia in Illyricum to further his studies, along with his friend Agrippa. Here he was to continue his education, while waiting to accompany Caesar on a campaign against the Dacians and the Parthians. Octavian was still a very minor player in the politics of Rome at this point, but his star was certainly on the rise. Caesar, having selected various political offices years in advance (one of many slights against Republican tradition), had slotted his nephew to serve as his right hand man, or master of horse, in the year 43 or 42 BC. At the age of 20 or 21, Octavian was expected to occupy the second most powerful position in the Roman world, but fate, and the Ides of March would have a different plan.

Caesar's Heir

On March 15, 44 BC, the Roman world was shaken to it's foundation with the assassination of Julius Caesar. Though the effect would prove to be staggering, (ie the plunge into yet another devastating civil war), no Roman was as profoundly affected as Gaius Octavius. Nearly 19 years old, Octavian was studying in Apollonia and awaiting the start of Caesar's next campaign against Parthia. Octavian's plan to join this campaign came to a crashing halt with the murder of his great uncle, and two equally possible roads soon opened to the young man.

When word reached Octavian of Caesar's murder, the naming of Octavian as his uncle's heir and posthumous adoption, reaction was mixed among his family and friends. His friends, likely Agrippa included, urged him to go to Macedonia and take refuge with Caesar's former legions there. His mother and step-father, L. Marcius Philippus on the other hand, pressed him to return to Rome as a private citizen and refuse Caesar's inheritance out of fear for his personal safety. Octavian sided in part with his family and decided to return to Rome, but readily accepted the adoption and the portion of Caesar's estate that was willed to him. He took the name Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, as was his right by virtue of adoption, but Octavianus was dropped from conscious thought. It's been used throughout the study of history to define him from his adoptive father, but he identified himself simply as Caesar. In so doing, he immediately entrenched himself as a favorite both with the masses and the all important veteran legionaries.

After making the decision to return to Rome to claim his inheritance, Octavian first crossed the Adriatic and landed in Brundisium, where he decided the safest course of action was an appeal to Caesar's troops. A bold and daring move, and seemingly necessary to ensure his safety, it turned out to be the only way to ensure his legitimacy. As Octavian marched to Rome, and gathered support among Caesar's Italian veterans, the de facto leader in Rome, Marcus Antonius, essentially ignored the youth. Not only did he blatantly disregard Caesar's will, but made no effort to discuss the situation with Octavian or learn of his intentions. When Octavian finally arrived in Rome in late April, 44 BC, Antony still ignored him, and still attempted to block passing on Caesar's inheritance. Octavian, however, garnered support from the masses and conflict seemed inevitable.

Antony was occupied with his own intentions of taking Cisalpine Gaul from then governor Decimus Brutus. Though the use of the Tribunes, Antony forced through legislation that altered his appointed governership of 43 BC from Macedonia to Cisalpine Gaul. Decimus Brutus, a former supporter of Caesar, yet a key player in the assassination, had the general support of the Senate, and of course, Caesar's assassins. Antony, however, had no intention of waiting for events to unfold and took matters in his own hands. In November of 44 BC, rather than wait for Decimus Brutus' term to expire, Antony moved on Cisalpine Gaul, where he hoped to gather further strength by pushing his control into all of Gaul. In the meantime Octavian, as he was being set aside by the powers that were as a man with a name but no authority, pushed the envelope of daring. He traveled among the veteran colonies of Campania and, risking the enmity of the state, raised a personal army perhaps as strong as 10,000 men. The weight of the Caesar name, as Octavian was still quite unaccomplished on his own merit, proved to be a powerful factor to reckon with.

Antony returned to Rome to deal with this new threat, but 2 of his 5 legions on the way from Macedonia to Gaul deserted him to Octavian's growing army. Rather than risk a war in Italy, Antony rushed back to Cisalpine Gaul with the forces he could muster, where he hoped to seize control from Brutus. At this point, there were three seemingly opposed factions vying for power, the 'Liberators' or Caesar's assassins, Antony and Octavian. The Senate, and Cicero in particular all viewed Antony as the greatest threat to Republican liberty, and he began a campaign of disgracing Antony through the use of his vaunted rhetoric. Viewing Octavian as a tool to be manipulated, the Senate accepted him as a counterforce to Antony's strength and legitimized his command, despite its illegal beginnings. By the close of 44 BC, the various factions continued to shore up their military positions, and war was once again on the horizon.

As Antony marched north to besiege Decimus Brutus in Cisalpine Gaul, Octavian, armed with the support of both Cicero and the Senate, readied his forces to follow. Having garnered the support of Cicero, though it was thought to be for the best interest of the Republic, Octavian actually secured his position as a political player of some importance. Despite attempts by the Senate to try and reconcile all the opposing factions, there was little chance now for resolution by peace. In the east, Caesar's assassins continued to spread their control, and in the west the various factions continued to build support for their own causes.

In April of 43 BC, Octavian marched north to face Antony, and was joined by the current consuls for the year, Pansa and Hirtius. The three men had mutual cause in defeating Antony, but otherwise the two consuls would have little use for Caesar's heir. The three commanders camped their armies separately near Bononia, not far from where Antony had Decimus Brutus besieged at Mutina. Antony broke off the siege with his main army, leaving his brother Lucius in command there. Antony drove down on Pansa first, defeating his Consular army, and inflicting what would become mortal wounds on Pansa himself. Next he sought to defeat Hirtius in turn, but the combined strength of two powerful enemies turned the tide against him. Antony retreated into Transalpine Gaul, where he hoped to build support from the Caesarian forces still in power there, but the armies of his enemies suffered a terrible loss. Not only had Pansa succumbed to his wounds, but Hirtius was killed in the battle as well, leaving the Republic without its Consuls. Decimus Brutus wanted Octavian to join forces with him and pursue Antony, but Octavian refused to join with one of the murderer's of his adoptive father.

While Antony fled and then joined forces with Lepidus, the pro-Caesarian governor of Spain, the Senate's faction attempted to shun Octavian and bestow prestige among Brutus and other allied parties. Among other slights, the Senate ignored land settlement requests for Octavian's veterans and refused to consider his petition to be named suffect Consul (along with Cicero) for the remainder of the year. While Cicero continued to support who he though was his young protégé, the assassins of Caesar saw the situation much more clearly. While Antony was a threat, to be sure, they feared Octavian, with his massive public popularity, as the continued presence of Caesar's legacy. Denying Octavian at every turn, the young man decided on another bold and daring move. Rather than wait for events to unfold, Octavian marched south, leaving Antony and Lepidus in a stalemate against Decimus Brutus and his allies.

Word had come to Octavian that the Senate and even Cicero, viewed him as a convenient tool to use against Antony. When the need was gone, the Senate would surely dismiss Octavian, but they underestimated both him, and his popularity with the legions. It's suspected that Antony may have even played a part, probably taunting Octavian with the fact that he was just an unwitting pawn in the Senate's power game.

As Octavian marched on Rome, the Senate was unable to put up resistance, with their main armies facing off against Antony and Lepidus in Gaul and the other 'Liberators' in the east. It's also interesting to note that while the assassins such as Brutus and Cassius participated in Caesar's murder as a pretense to preserving the Republican tradition, they seemingly has no qualms about illegally taking control of they eastern provinces to build their own strength. Regardless, the Senate initially accepted Octavian's demands, such as naming him Consul and granting land to his veterans, but when word arrived that legions had arrived from Africa to support the Senate, the offers were rescinded. These legions, however, refused to fight Caesar's heir, and switched their loyalty without a single engagement. As the calendar reached mid summer, Octavian, still only 19 years old, was confirmed as Consul along with his cousin Q. Pedius and set about an extraordinary bit of political legislation. He seized the state treasury, paying off his troops, and finally received the distribution of Caesar's will. More importantly, however, he changed the focus of Senatorial politics by authorizing a special law revoking the amnesty of the 'Liberators'.

In one single day, he tried and convicted Caesar's murderers in abstentia, and set stage for the civil war to finally end the collapsing Republic. Octavian rose to power as the first Roman in history to do so almost completely with the support of the army. Unlike previous political powerhouses, like Marius, Sulla and Caesar, Octavian had little to any real support among the political forces that were. As a young man without an established client base, the maneuverings of men such as Cicero helped set him up on the public stage, but it was the legions, and the use of his adoptive name, Caesar, that secured his position among Rome's elite. By the autumn of 43 BC, Octavian prepared for his next move, to alter the state of the political landscape and reconcile with Antony.

Second Trumvirate

After forcing through his own political agenda in Rome, the situation with Antony was still precarious. Antony had reached Gaul and gathered strength from the legions stationed there. Together with Lepidus in Spain, the two were a formidable force. Octavian, despite having considerable strength himself, would be hard pressed to meet that challenge alone.

By passing a law that found all the members of Caesar's assassination plot to be guilty of a capital crime, he certainly couldn't count on any support from that quarter, not that he wanted it. Decimus Brutus, for so long holding the support of the Senate against Antony, now found himself sandwiched between Antony, Lepidus and Octavian, and decided to flee to the safer eastern territories. He was not so lucky, however, and was captured and executed en route, becoming the first of the major players in Caesar's murder to pay for his 'crime'.

Octavian decided that the prudent course of action was to reconcile with Antony and stabilize the Caesarean faction. He marched north and met with Antony and Lepidus on a small river island near Bononia. For two days the three political leaders of the western Roman world hammered out the details of an agreement that would set them up as the official government of Rome. In establishing the triumviri rei publicae constituendae, the three men divided the western 'empire' between them.

Antony would stay entrenched in Gaul, Lepidus, the leading pro-consular patrician member of Roman government still alive, maintained control of Spain and Narbonensis and Octavian received Africa, Sardinia and Sicily. Octavian's status as the junior member of the group relegated his authority to these more minor territories, by comparison. Not that they weren't important, but Sextus Pompeius, son of Pompey the Great, had already established himself as a pirate captain in the Mediterranean and made control of Octavian's provinces difficult at best. By the time the Second Triumvirate was cemented, Pompey had already taken control of the islands, and was lurking dangerously off the Italian shore.

This Second Triumvirate was different than the First arranged by Caesar, Pompey and Crassus some 16 years earlier. While the first was really a secret pact that forced the 3 men to pledge mutual support, leaving the Republican system largely intact, this new triumvirate was a legal arrangement, written into the constitution by the Lex Titia in November, 43 BC. In essence, this new government was a joint dictatorship, where the three members had ultimate authority capable of completely disregarding Republican and Senatorial tradition through the use of military force.

With their agreement firmly in place, the triumvirate first focused on both gathering enough funds to stabilize their authority and eliminate political opposition. This meant the return of Sulla's dreaded political tool, the proscriptions. There is some dispute whether the proscriptions were intended merely as a means for financial gain, or directly intended as a political affirmation, but regardless, the use of proscription produced both results. Being sure not to make the mistake Caesar had made in pardoning his most dangerous threats, the proscriptions of the second triumvirate were as brutal and all encompassing as those of Sulla.

In all, some 130 to 300 Senators were proscribed, but most only faced confiscation of property. Worse though, estimates of up to 2,000 equites were said to be on the proscription list. Members of the Triumvirs own families were not exempt either. Lepidus' own brother was proscribed, as well as Antony's cousin and Octavian's distant relative through adoption, Lucius Caesar. Though they survived and their proscription was a matter of financial necessity, it was clear that the Triumvirs would use any means necessary to advance their agenda.

The most notable victim of the proscriptions was Marcus Tullius Cicero. After having opposed Antony for so long, including vicious attacks through the use of his rhetoric and oration, Antony simply couldn't allow Octavian's mentor to live. Despite Cicero's support of Caesar's heir, Octavian agreed that Cicero had to go. On December 7, 43 BC, Cicero was captured attempting to flee to Greece, and the relative safety of the 'Liberators' provinces. Much like the proscriptions of Marius and Sulla, Cicero's head and hands were cut off and displayed on the Rostra in the forum. Unlike their predecessor's mass displays, however, Cicero was the only victim to be publicly exhibited this time around. To add insult to injury, and as a symbolic gesture against Cicero's vaunted power of speech, Antony's wife, Fulvia pulled out Cicero's tongue and jabbed it repeatedly with a pin.

Though the proscriptions didn't yield as much financial gain as the triumvirs had hoped, they did provide enough of a boon to turn their attention on their mutual enemies in the east. Despite a certain animosity between them, they were secured by the presence of a common foe, and the triumvirate was stable for the time being. The next year, 42 BC, would be focused on eliminating Caesar's assassins and strengthening their own power.

Philippi

In 42 BC, Octavian and Antony combined their forces, 28 legions in total, and sailed across the Adriatic and into Greece. The 'Liberators' Brutus and Cassius had 19 of their own legions, which were heavily supplemented by auxilia provided by eastern client kingdoms.

Brutus and Cassius had been plundering and taking control of the east for nearly two full years since the murder of Caesar. Despite having an army made up largely of Caesar's former troops, they used this plunder and distributed it among the men to secure their loyalty.

As Octavian's and Antony's armies arrived and assembled near Dyrrhachium, the site of Caesar's near defeat to Pompey 6 years earlier, Octavian battled with his own poor health. Often described as a sickly youth, he was apparently stricken with a terrible illness just as the fate of the Roman world was about to be decided. Antony, however, likely saw a grand opportunity to win a great victory for his own cause without being forced to share any credit with his young fellow triumvir and rival. As Antony marched his army east towards the Macedonian - Thracian and border and confrontation with the enemy, Octavian had no choice but to follow, despite his illness, or risk being left out of the battle to revenge his adoptive father.

Initially both sides jockeyed for position, and the 'Liberators' hoped to win a battle of attrition by delaying Antony's advance. Antony however, often considered second only to Caesar in military ability during this era, would have none of it and forced the enemy into battle. On October 3, the two armies drew up near the Macedonian town of Philippi. Cassius commanded the left wing of the Republican forces directly across from Antony while Brutus confronted Octavian's army with the right wing. Octavian, however, despite his presence in the area was still terribly ill.

He was forced to stay behind the lines in his tent, while his officers conducted the battle on his behalf. As the battle opened, Antony had a clear advantage over Cassius, and overran the Republican left. Brutus, though, had nearly equal success against Octavian and pushed his lines back. Octavian was forced to flee his camp, taking refuge in a nearby marsh.

Cassius' defeat was significant and yet the entire affair could've been stabilized by Brutus's success. Cassius though was certainly unaware of his ally's good fortune and decided to take his own life, rather than submit to Antony. Despite his own loss, Cassius was the stronger military mind of the Republican side and his own death began to sound the end of their ability to resist. Brutus managed to regroup and take command of Cassius' remaining army, but the writing was on the wall. Antony assuredly reveled in his own victory while Octavian was forced to retreat, but Brutus held his ground and delayed Antony's triumph. On October 23, perhaps losing the confidence of his men, or willing to risk a final last ditch effort at victory, Brutus launched an attack.

At the Battle of 2nd Philippi, Octavian was seemingly recovered from his illness and commanded his own army. He and his men were certainly embarrassed by their defeat just 3 weeks earlier and were prepared to give a better account. This time they proved themselves up to the challenge, and the triumvir's army overran Brutus. Octavian's forces captured Brutus' camp and they were atoned for their previous defeat.

The battle spelled the end of the Republican cause, and Brutus committed suicide on the following day. A great number of those involved in the plot against Caesar also lost their lives at Philippi and Octavian was brutal in exacting vengeance. Though some escaped to join with Sextus Pompey in his Sicilian stronghold, the battles of Philippi essentially assured the end of Republican government and paved the way for a final conflict between the victorious triumvirs.

After the battles, Octavian marched his army back to Italy, where he was now faced with the unenviable task of finding a retirement settlement for his veterans. Antony continued east where he began to secure loyalty of client kings and provincial governors alike. He imposed serious penalties on Asia Minor in particular and essentially plundered those provinces for disloyalty, despite already having been looted by Brutus and Cassius.

In light of the altered state of the Roman world, the triumvirs realigned their positions. Antony received the entire east as his new territory, yet retained Transalpine Gaul. Octavian now moved into the second position among the three received Spain, Italy, Cisalpine Gaul and the Mediterranean islands. Lepidus, clearly relegated to third on the list, was moved to Africa, where he would essentially linger as a bit player in the remaining days of the Republic.

War between Antony and Octavian

As the legal arrangement for the triumvirate between Octavian, Antony and Lepidus (even though he was no longer an official part of the arrangement) expired at the end of 33 BC, 32 BC turned into a year of political posturing and strained anticipation. Without legal triumvir powers, Octavian technically reverted to no more than a leading member of the Senate, and the Consuls for 32 BC, Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus and C. Sosius both Antony supporters, sought to bring Octavian down.

While Octavian was outside of Rome, Sosius launched an attack on Octavian's legal position to the convened Senate. Though the precise nature of the attack is unknown, it's safe to assume that the Antony supporters definitely wished to limit Octavian's power and position. What they surprisingly failed to count on was Octavian's support among the army and his boldness in using it. When he returned to Rome he called the Senate to meet, backed by an armed escort, and proceeded to turn the tables on the sitting consuls. Launching his own attack on Antony, it was clear that the Roman world was once again heading towards civil war. In Rome, despite Octavian's lack of legal right to rule, it was also quite clear that he was in fact, the unchallenged leader of the west. Not even Antony's supporters attempted to dispute him, and many Senators (up to 300) fled to Antony, rather than attempt to put up a false front that all was well.

News soon returned to Rome that Antony intended to set up a separate eastern Senate in Alexandria to govern the eastern part of the empire. He also officially divorced Octavian, denouncing her in favor of the foreign Queen, Cleopatra. Octavian knew that war was coming, but now needed to rally support among the masses. By fortunate circumstances, two important supporters of Antony had defected to Octavian's cause and returned to Rome about this time. L. Munatius Plancus and M. Titius brought word to Octavian that Antony's will, now deposited with the Vestal Virgins, contained incriminating evidence of Antony's anti-Roman, and pro-Cleopatra stand. Both men, it seemed, had been witnesses to the document, and Octavian illegally seized the will from the Vestals. In it, Antony recognized Cleopatra's son Caesarion as Caesar's legal heir, propped up his own eastern appointments by leaving large inheritances to his children by Cleopatra, and finally indicated his desire to be buried with Cleopatra in Alexandra. Though the first two matters wouldn't be considered all that unusual, it was the third that set off a firestorm of anti-Antonian sentiment. Already suspecting him of abandoning Rome for Cleopatra, the people clearly saw his rebuttal of Roman cremation tradition and the favoring of eternal burial with Cleopatra as proof of him falling under the Queen's sway.

Octavian seized the opportunity to gain from the people's sentiment, and encourage the rumors that followed. If the people believed that Antony had every intention of making Cleopatra the Queen of Rome, and by virtue of his new eastern Senate would move the capital to Alexandria, it could do nothing but favor Octavian. He was reserved in his intentions, however, and knew that Antony still had some supporters. Civil War too, simply for the benefit of Octavian would never be popular. He also wished to make it easy for Antony supporters to willingly switch sides without seemingly being disloyal. Rather than announce war with his rival Antony, Octavian declared war on the hated Queen Cleopatra, the perceived cause of all the trouble. As both sides geared up for the conflict that would seem to be the largest and costliest ever for the Roman state, a remarkable show of public support took place. The people of Italy and the western provinces swore on oath of loyalty directly to Octavian, rather than the Roman state. Though this was likely a greatly orchestrated political maneuver by Octavian, a now brilliant politician, it had the desired effect of at least giving him the public support he needed to take the nation to war. While by no means presenting Octavian with any sort of legal power over the Roman world, it did help to clarify for everyone that not only did Octavian maintain power through the legions, but also through the good will of the Roman people.

Actium

The civil war between Antony and Octavian seemed assured of dwarfing even the massive conflict between Caesar and his Republican opponents. Both sides had massive armies at their disposal, and Antony added the support Rome's eastern client kings, including Cleopatra of Egypt. By mid-summer of 31 BC, Octavian's war against his rival, though popularly characterized as being against the Egyptian Queen, had worked itself into little more than a stalemate. Antony had marched his army into Greece where he planned to oppose Octavian's advance, and the two considerable forces began to take up position against one another.

While the armies were of relatively equal strength, Octavian's fleet was vastly superior. Antony's fleet was made up of large vessels, though with inexperienced crews and commanders. On the other hand, Octavian's fleet of smaller, more maneuverable vessels was under the command of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the proven admiral who excelled in the war against Sextus Pompey. While Octavian crossed the Adriatic to confront Antony near Actium in Epirus, Agrippa menaced Antony's supply lines with the fleet. Octavian wisely refused to give battle with the army, and Antony did likewise at sea. As the summer waned, both armies seemed to settle in for a battle of attrition.