The Laskaris Restoration of the Roman Empire, Part 1 (1450 - 1479 AD)

Historians refer to the early period of the Laskaris Dynasty as the “Laskaris Restoration.” This period saw the remarkable reigns of Emperor Theodoros I and (most importantly) Emperor Skantarios Laskaris. These two successive Emperors oversaw the reconquest of what was once the Eastern Roman Empire as well as huge stretches of territory in the west and the far east. During their reigns, the Roman Empire expanded from just a sliver of Greece and the city of Constantinople to territorial limits not seen since the time of Justinian. This explosion of conquest was due to two primary factors: the strength of the walls of Constantinople and the military brilliance of Skantarios. This is the history of that remarkable period of time.

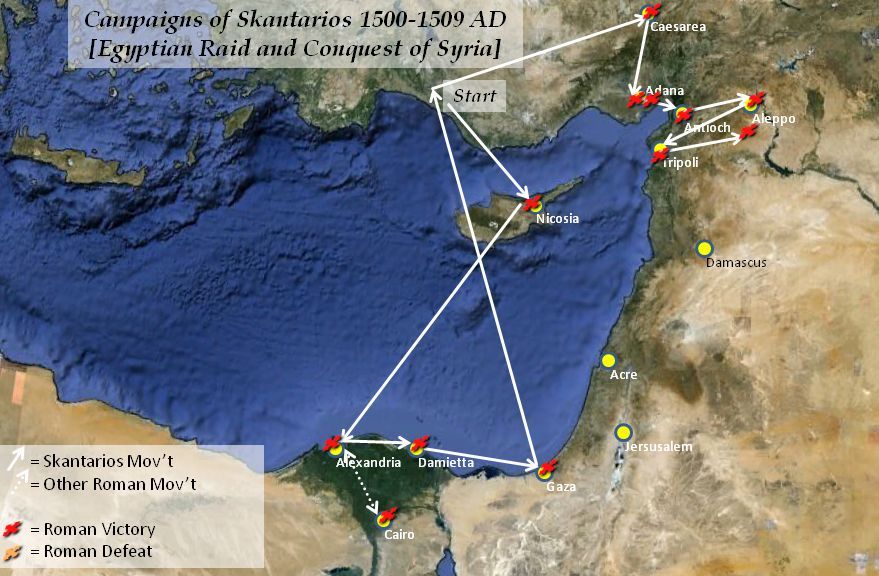

Historians are fortunate in that the memoirs and diaries of Emperor Skantarios (and some of his generals) were published after his death. They tell in vivid detail the strategies, tactics, motivations, and political intrigue of that era. They are so copious that to tell the full story of the military campaigns of his time would fill volumes. Therefore, this narrative will concentrate almost exclusively on the operations that Skantarios himself participated in and only give cursory mention to the other generals of that era.

Where necessary, sidebars will be added to give better illumination in other theaters of war or to expand on certain aspects of the time that greatly affected Skantarios’s pursuit of the war.

The Early Years (1450 – 1453).

(see Prologue for events leading up to 1450)

The assassination of Demetrios provided the young Sultan Mehmet the perfect excuse to renew war with the Romans. Mehmet had long coveted Constantinople as the new capitol of his expanding Turkish Empire. In fact, Mehmet had recently offered Emperor Constantine XI lands in northern Greece if he would relinquish Constantinople peacefully. Constantine’s refusal to do so was the catalyst for Demetrios’s coup and led directly to the subsequent overthrow by Theodoros.

Following the successful coup of Theodoros and Skantarios in March 1450, few would have given the Roman/Byzantine Empire much hope for continued existence. The once mighty Roman Empire now consisted of nothing but the city of Constantinople and the Peloponnese. The treasury was essentially bankrupt and the succession squabbles and rebellion in recent years had robbed the Empire of most of its wealth, soldiers, landed nobility, and field commanders.

When Theodoros came to power, he not only had to deal with the Seljuk Turks but also deal with a fresh war with Venice. These were two of the most imposing empires of that age. The Seljuk Turks were generally acknowledged as the greatest land power in Europe and Asia, and Venice was considered the greatest sea power. The Romans, on the other hand, had only a tiny navy and very few troops. What troops they had were mostly new recruits to replace the losses following the Battle of the Hexamilion some three years before.

By the normal conventions of the age, the Romans should have accepted vassalage to the Turks and looked for expansion elsewhere. However, subservience was the antithesis of what Skantarios and Theodoros believed and what they preached when they had come to power. Also, in truth, there were no more concessions they could make to the Turks – there was simply no land left to give up. War was inevitable and would be prosecuted to whatever end it brought.

As Constantinople was the obvious focus of the Turks, Emperor Theodoros took charge of the city and its defenses. He bolstered the number of infantry defenders and recruited what archers he could. He even took the extraordinary step of sending away the Roman heavy cavalry in the city to Skantarios in the Peloponnese as they would be virtually useless in the defense of the city but might prove of value to the field army. Even the energy of Theodoros could not make up for all the military weakness of the city. The available manpower was very small and the garrison was woefully inadequate.

In the Peloponnese, Skantarios took charge of what meager field forces were available and made tireless recruiting drives to gather more men. It was a difficult sell to the peasantry that remained as no one believed they had much, in any chance. One bit of luck the Romans did have was that the Turks were myopically fixed on Constantinople and expansion north and the Peloponnese was, for the moment, forgotten and relatively secure. Skantarios used this one last base of power to strike out against the Venetians at Athens in a repeat of Constantine XI’s strategy in the 1440’s. Unlike Constantine, Skantarios did not come to raid but to conquer.

The Venetians were a ripe target for conquest. Although they possessed the largest navy in the world, they had neglected their land forces. The garrisons of their major cities were somewhat weak and their field armies were scattered throughout Italy, Greece, and the northern coast of the Black Sea. The animosity between the Romans and the Venetians went back all the way to the Fourth Crusade of 1203-4 which culminated in the conquest of Constantinople. Although relations had improved somewhat in the following centuries, their present collusion with the Turks put them in direct conflict with the Romans. Also, the territories in and around Greece were rich and Venetian merchant holdings would provide the Romans with desperately needed money. Finally, Skantarios believed he could take these cities without bringing immediate reprisals by the Turks. In this, he was proven correct.

In 1451, Skantarios took Athens by direct assault and expelled or killed all the Venetians administrators and merchants in the city. He then seized some Venetians ships in the harbor and made directly for Crete while leaving only a tiny garrison in the city. The crossing was done in secret and Skantarios was able to make landfall on the island. He moved quickly south and then fought a successful battle outside Iraklion that utterly destroyed the entire Venetian army and nobility on the island. Again installing only a tiny garrison at Iraklion, Skantarios returned after less than a month on the island back to the Peloponnese. In only one year, the Venetian power in Greece was eliminated and the Romans had almost doubled the territory under their control.

The success of this early campaign emboldened the Greeks who now flocked to Skantarios’s banner in Mystras. By 1453, Skantarios felt sufficiently strong to directly challenge the Turks by moving into Thessaly and laying siege to Thessalonica which he took in the following year.

Spoiler for New Method of Warfare:

War with the Seljuk Turks Begins (1453-1459)

The Roman success up to this point was greatly aided by the Turks splitting their focus between Constantinople and northern expansion into the independent lands around Bucharest and Brasov. However, when Skantarios took Thessalonica, the Turks halted their northern advances and moved against both him at Thessalonica and Constantinople itself. They clearly intended on destroying the upstart Romans quickly and consolidating their holdings in Europe.

Theodoros was able to withstand the first Turkish assault on Constantinople in 1455. Meanwhile, Skantarios pursued a guerrilla campaign against the Turks in the Pindus Mountains of northern Greece for the next three years. By 1458, the Turks were obliged to weaken the garrisons of their eastern European holdings in order to concentrate their offensive power against Constantinople and reclaiming Thessalonica. The threat to the weakly defended Thessalonica compelled Skantarios to come down from the mountains and fight the Turks in the open. However, instead of the easy victory the Turks (and everyone else) expected, Skantarios destroyed the Turkish army and lifted the siege of Thessalonica. This marked the first defeat of a full Janissary army in modern memory. Skantarios followed up that victory with a quick strike west and seized the now weakly-defended fortress city of Arta on the Adriatic. These victories were extremely costly for the Romans but provided enough breathing room for Thessalonica to remain in Roman control and gave Skantarios time to recruit and train new troops.

In 1459, Constantinople successfully fended off a second Turkish assault. The twin successes at Thessalonica and Constantinople had enormous strategic repercussions as it convinced the Kingdom of Hungary to join the war against the Turks and form an alliance with the Roman Empire. This alliance was sealed through a royal marriage between Skantarios and Princess Maria of Hungary.

Spoiler for Campaign Map for 1459:

Spoiler for Alliance with Hungary:

The High Point of the Romano-Turkish Wars (1459-1470)

Skantarios followed up his success at Arta with an assault on the mountain fortress of Scopia in 1459. By this time, he was playing a dangerous game of maneuver with the Turkish Army. Skantarios had insufficient strength to directly challenge the Turks and they were stymied in their efforts to locate the Roman field army. The Turks committed two full armies to destroying him but could not close with the elusive Romans. Skantarios exploited his knowledge of the land (and the sympathetic local populace) and continued to move north and south through the Pindus and avoided contact with the main armies. In classic hit and run tactics, he fought several battles against supporting columns of the Turks but only when the odds favored him.

On the diplomatic front, there was a severe setback when both the Egyptians and the Papacy declared war on the Romans in 1460. Conclusive evidence of collusion between the Egyptian court and the Pope was never found but the perception in the Roman Empire was that these two seemingly intractable enemies were working in concert under a secret treaty. There were indications in later years that the Pope and the Egyptian Sultan had drawn up a secret pact dividing the world between them with the Egyptians holding the east and the Pope in control of the west. The dividing line was to be Constantinople.

By 1463, the Turks had had enough of this game of cat and mouse. They forced Skantarios’s hand by laying siege to Thessalonica again with another full Janissary army while simultaneously committing another Janissary army to besiege Constantinople. This was a repeat of their tactics from five years before. As before, the loss of either city was rightly judged to be unacceptable to the resurgent Romans and forced Skantarios into an open field battle.

Skantarios had made good use of the past few years and recruited enough soldiers in the Peloponnese to bring his forces to rough parity with the Turks at Thessalonica. Skantarios led his men out of the mountains and, combined with the garrison of the city, delivered a crushing blow by annihilating the Turkish army outside the city. The defeat was so decisive that the Turkish army at Constantinople broke off their siege without a fight and returned to Adrianople.

With the seizure of Scopia and Arta, the Romans were once again in contact with Venetian territory. In 1465-66, Skantarios recouped the Roman field army at Scopia. It was there he came in contact with and defeated two consecutive Venetians armies, killing the Doge of Venice in 1465 and his successor the next year (Doge Barbus killed in battle, Doge Pietro executed when his ransom was refused).

In 1467, Skantarios came out of the mountains once again and seized the town of Durazzo from the Turks. The next year he took the citadel of Ragusa from the Venetians. Following the seizure of these two cities, Skantarios brokered a deal with the Hungarians to exchange both Durazzo and Ragusa for the fortress of Sofia. This was done to shield the Empire from the Papal-influenced Catholic nations of the West, further consolidate Roman control of the Balkans, and bring the expanding Roman territory in the west closer to Constantinople.

Spoiler for Campaign Map for 1469:

Spoiler for Tide Turns Against the Seljuks:

Roman Victory in Eastern Europe (1471-1479)

The land swap with Hungary consolidated Roman holdings in Europe and provided a stable base for further offenses in Europe. An added benefit of the acquisition of Sofia was that Skantarios could now draw on the ethnic-Magyars and Serbs for fresh recruits in his army. These fierce tribal people had no love for the Turks and provided the Roman Empire with excellent heavy cavalry and horse archers. They provided a welcome relief for the already over-stretched peasantry of Greece.

The addition of these forces and the growing strength of the garrison of Constantinople allowed the Romans to embark on their most audacious offensive yet. In 1472, Skantarios and Theodoros collaborated on a dual assault with Bucharest and Adrianople as the targets. Skantarios, as he had done so often before, managed to avoid the main Turkish armies in Thrace and move north to assault the strong Turkish garrison at Bucharest. He annihilated the forces defending the city in a brilliant battle where he was outnumbered by more than two-to-one.

In the same month in 1472, Theodoros led the garrison of Constantinople out of the city and assaulted the fortress city of Adrianople. The defenses of the city had been compromised and the surprise attack quickly overwhelmed the Turkish defenders and brought the fortress under Roman control. Theodoros installed a strong garrison and then returned to Constantinople before the Turks could respond. In less than a month, the Romans had taken both cities and nearly expelled the Turks from Europe.

The Turkish reaction was swift. Within a year, they had laid siege to both Adrianople and Constantinople. Their hopes of reviving their fortunes in Europe were dashed however when the garrison at Adrianople won a very close victory when the Turks assaulted the city in 1473. Theodoros then successfully held off the Turks in their third assault on the city in 1474. The Third Battle of Constantinople was particularly significant as it was the first use of Greek Fire by Roman ground troops (Siphonatores) in several hundred years (the secret being rediscovered by Theodoros in the 1450’s). The destruction of the twin Turkish armies at Adrianople and Constantinople left the garrison at Brasov as the only significant Turkish force still left in Europe.

Later in 1474, the Romans were rocked by the murder of Emperor Theodoros at the hands of an Egyptian assassin. The death of Theodoros brought the Roman reconquest of Eastern Europe to a standstill for the next few years as Skantarios was obliged to return to Constantinople in order to establish firm control over the government and ensure the loyalty of the nobility.

By 1477, Emperor Skantarios was ready to take the field once again. Due to a lack of reliable generals at the time, he was forced to put Constantinople under the command his younger brother and heir, Vasileios who was only 16 at the time. Vasileios ruled the city jointly with his mother, the dowager Empress Maria, when Skantarios left for the north to finish off the Turks in Europe.

Skantarios took the bulk of the newly christened Imperial Army north for the assault on Brasov. The assault was delayed for a year as the Hungarians tried and failed to take the city themselves. By 1479, Skantarios was ready and assaulted the citadel and its powerful garrison. It fell in a bloody battle that saw almost 40% casualties for the Romans. Skantarios was criticized at the time for taking the fortress by direct assault and not either starving the garrison out or at least bringing up more troops. However, Skantarios had great need of haste for now all the great powers of Islam were aligned against the Romans.

Jihad had been declared on Constantinople.

Spoiler for Campaing Map for 1480:

Spoiler for Causes of the First Jihad:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote