The RS 2.0 Team Proudly Presents.....

A Kingdom in the Sands

In 305 BC a new power was born. From the post Alexandrian chaos emerged the first of the great states of the Hellenistic world, the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

For almost a century now, your dynasty has ruled Egypt, mingling newer Hellenic traditions with the mighty legacy of the Pharaohs. The great labours of your ancestors have led to the formation of a mighty Empire that spans across the far reaches of southern Syria in the east to Cyrene to the west, and extending south to the dangerous frontier with Nubia. Across the Mediterranean peoples in along the southern coast of Asia Minor hail you as their king and pharaoh. The Greeks and Thracian peoples of the Thracian Chersonese also bow to your wishes with obedience!

Despite an air of tranquillity, your lands are far from peaceful. The memory of the Laodicean War still echoes throughout your kingdom as uneasy rumours begin to spread. The blood spilt to recover the lands of Syria and Anatolia is still fresh on the minds of the oldest of your subjects. Nor is your kingdom safe from internal strife that has caused so much heartache in this region. And yet an uneasy peace has allowed prosperity to take hold throughout your lands. But for how much longer?

On the borders of your flourishing empire, an old enemy stirs. Egypt is seriously threatened by Antiochus III, the Syrian Seleucid ruler. Bent on avenging the humiliation caused by the peace that ended the Third Syrian War, his armies will stop at nothing to gain a foothold in the lands of your ancestors.

In 219 B.C the Seleucid ruler shows his hand, capturing some of the coastal cities that are so valuable to trade and commerce in your Empire. As the ports of Seleucia-in-Piera, Tyre, and Ptolemais fall, you can stay your hand no longer! Despite the delaying actions of the Ptolemaic court, war is at hand! So grave is the threat that for the first time under the Ptolemaic regime, native Egyptians are to be enrolled into the infantry and cavalry and trained in phalanx tactics! A shrewd move to increase the power of your armies or a desperate step from a failing ruler?

The fates themselves conspire to decide the destiny of your kingdom in the spring of 217 B.C. in the small town of Raphia. Forced to recruit large numbers of natives into your army for the first time, the soldiers of the Greeks, Macedonians, Gauls, and others stand with you and you alone, Pharaoh, and this great army will fight as one in your honour. A great and decisive victory here will surely win you the war and a free hand to march north into the Seleucid Syrian heartland, but beware as a loss will spell doom for the Ptolemaic kingdom and leave the way to the Delta and Alexandria open for Antiochus the Syrian to take.

So onwards, mighty Ptolemy and great pharaoh! To battle and victory!

The Ptolemaic World View

The world as we know it is changing. Great powers rise to the West and the East. Lands that were once safe and sacred are peaceful no longer. Our armies must march. The world beckons....

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

(My thanks to Thomas Lessman, who made this map available. More maps can be found at www.WorldHistoryMaps.info)

The scholars of the Ptolemaic Kingdom were learned in the art of map making and mathematics, using knowledge passed down from both the Hellenistic world and the ancient knowledge residing in Egypt. Eratosthenes, who accurately measured the size of the world, was one such famed scholar.

The People of your Kingdom

At the death of Ptolemy II, 88 years had passed since the great coming of Alexander to the Egyptian lands. In those years, Ptolemaic Egypt began to take shape, blending Hellenic practices with those of the ancient Egyptians. Despite absorbing the traditions and even the gods of this once pioneering land, the land of Egypt ceases to be for the Egyptian peoples.

The original inhabitants of the land, those descended from the great kingdom of the Pharaohs were subjugated, performing their daily roles as normal, but for the benefit of a new, emerging Hellenic kingdom, the dynasty of the Ptolemies. No longer were the ancient peoples of this land the primary focus of trade and development, no longer did they have much say in the running of their kingdom. Mass multitudes of strangers, men from the rolling hills of Europe, from the deserts of the East swarmed through the country, settling and trading. Like a plague upon the original inhabitants of this bountiful land, they took over completely.

Instead of the grand country houses of the Egyptian nobles, which stood as a symbol of prowess and wealth in the olden days, the great estates now belonged to Greeks. Any Egyptian who aspired to rise through the ranks and make a name for himself learnt Greek, acquired a Greek sense of style and dress, and took service at the Greek court or under some Greek government official. Hellenic customs began to spread like wildfire amongst communities which had once worshipped the mighty traditions of the Pharaohs. In some cases the populace kept their Egyptian name, in others they abandoned their past for a Greek name or sometimes even, they took both an Egyptian and a Greek name.

The poorer Egyptians continued to talk their old language in a later form, on its way to become the Coptic of Christian Egypt. The old warrior caste of Egyptians, whom the Greeks in their tongue called machimoi or fighting men continued to exist distinct from the ordinary Egyptian peoples.

The Great Library of Alexandria

"And concerning the number of books, the establishment of libraries, and the collection in the Hall of the the Muses, why need I even speak, since they are all in men's memories?"

-- Athenaeus [1]

"The library of Alexandria is a legend. Not a myth, but a legend. The destruction of the library of the ancient world has been retold many times and attributed to just as many different factions and rulers, not for the purpose of chronicling that ediface of education, but as political slander. Much ink has been spilled, ancient and modern, over the 40,000 volumes housed in grain depots near the harbor, which were supposedly incinerated when Julius Caesar torched the fleet of Cleopatra's brother and rival monarch. So says Livy, apparently, in one of his lost books, which Seneca quotes."

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

When he became King, Ptolemy ordered that the capital of Egypt be changed from Memphis to the city of Alexandria. Steeped in myth and legends, tales of splendour and beauty the city is synonymous with the Great Library of Alexandria. Ptolemy was a man of the science and learning and as such he decided to make Alexandria a city of knowledge and understanding, to reflect his outlook.

The first mention we have of the library is in The Letter of Aristeas (ca. 180-145 B.C.E.) According to Aristeas, Demetrius recommended that Ptolemy I gather a collection of books on kingship and ruling in the style of Plato's philosopher-kings, He was urged to gather books of all the world's people that he might better understand subjects and trade partners, gain knowledge about cultures and various practices from around the world. The great library and research centre would be called the Museion, “named after the Greek goddesses of science and learning, Muses”

After Ptolemy I died, the library continued to grow under his son Ptolemy II. It gained its many books mostly by seizures from homes and ships in Alexandria with the ruling family often ordering homes and docked ships to be searched and their books to be taken to the library, either to be kept or to make copies of them. The languages of the books varied from Greek to Hebrew, the recorded knowledge of the known world slowly being drawn to this great centre of learning. The Kin called upon rulers of other nations for texts and had plentiful Jewish and Buddhist scriptures, among other religious books. Many of these religious works were translated by religious scholars actually at the library.

The Library of Alexandria expanded evermore, and eventually could not comfortably house any more materials. “During the reign of Euergetes, the number of books grew so large, a second library [or “daughter” library] had to be built” (Trumble 8). This “daughter” library of the Library of Alexandria was called the Serapeum, named after the god Serapis. The Serapeum was much smaller than the main library and is often times referred to, along with the main library, as the Library of Alexandria.

It was a pinnacle of learning and understanding. Scholars at the library mapped and measured the Earth and stars and produced the “greatest work of ancient astronomy, the Almangest of Claudius Ptolemy” (Stille 247). According to some references, “Ptolemy [i] invited the great mathematician Euclid to Alexandria and Euclid’s famous Elements of Geometry bore a dedication to Ptolemy” (Stille 247). The Library of Alexandria even contained, eventually, the Greek philosopher Aristotle's collection of books

A good source estimating the number of books housed in the libraries is the twelfth-century writer John Tzetezes. Although Tzetezes’ ancient sources of this information are lost today, there are records that Tzetezes wrote that, according to his source(s) at the time, there “were 42,800 books in the Serapium, and 400,000 mixed books and 90,000 unmixed books in the main library”

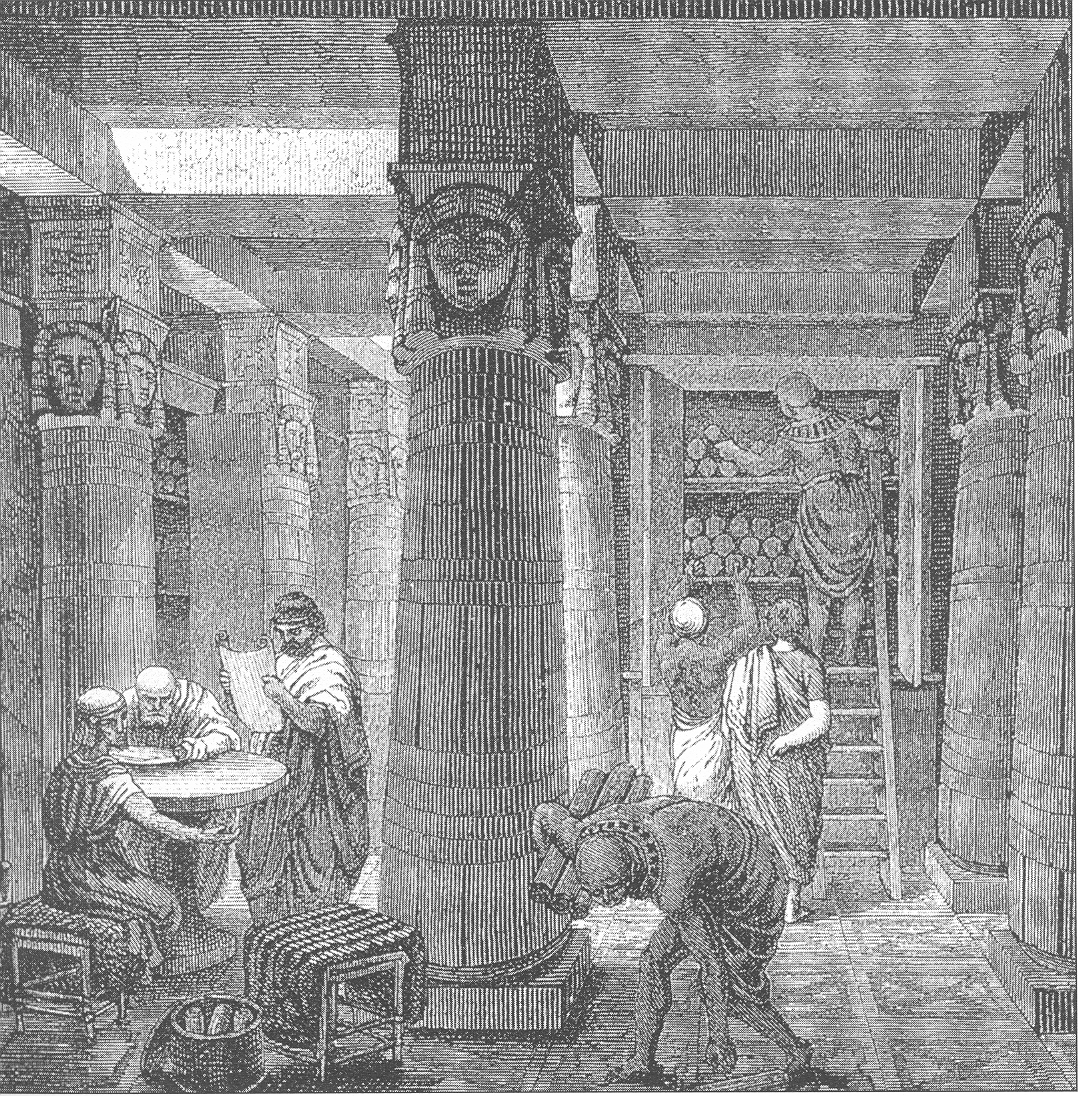

Views of the old Library:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

A reconstruction of the main hall of the Museum of Alexandria used in the series Cosmos by Carl Sagan. The wall portraits show Alexander the Great (left) and Serapis (right).

In this reconstruction, the doors from the Museum lead to storage rooms for the Library. Most of the books were probably stored in armaria, closed, labeled cupboards that were still used for book storage in medieval times.

Destruction of the Library

The legendary account of its destruction is as follows:

It is often said that the Romans were civilised but their most famous general was responsible for the greatest act of vandalism during antiquity. Julius Caesar was attacking Alexandria in pursuit of his archrival Pompey when he found himself about to be cut off by the Egyptian fleet. Realising that this would leave him in a desperate predicament, he took decisive action and sent fire ships into the harbour. His plan was a success and the enemy fleet was quickly aflame. But the fire did not stop these and jumped onto the dockside which was laden with flammable materials ready for export. Next it spread in land and before anyone could stop it, the Great Library itself was blazing brightly as 400,000 priceless scrolls were reduced to ashes. As for Caesar himself, did not think it important enough to mention in his memoirs.

A legendary library:

The Library Today

Today almost nothing remains of the Library of Alexandria. There is little to no useful knowledge that has been gathered from archaeological expeditions, with most of the knowledge being lost to the sands of time.

Today, even though the old Library of Alexandria has no factual existence, the spirit of the library still lives on in the city of Alexandria. Recently, the Egyptian government opened a new library, with a huge collection, that honoured the old library. The so called “New Library of Alexandria” was opened in 2002 and named the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. The city of Alexandria was a wonder in the ancient world, and that wonder lives on to this day.

The library contains more than 8 million books and a reading area with two thousand seats. This new library possesses about 400,000 volumes in hard and electronic copies. It is designed to hold 4 million volumes. In the future its capacity will reach 8 million using the compressed storage system. A fitting tribute to what was once the greatest collection of knowledge in the known world.

A view of the new library:

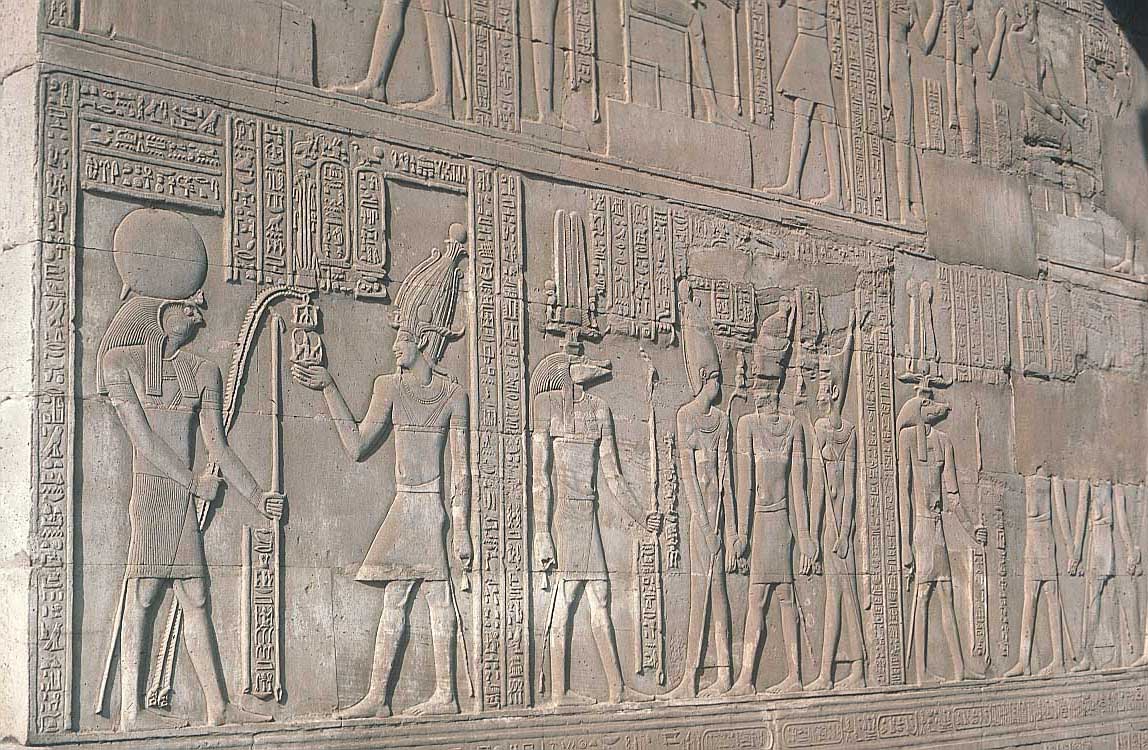

The Great Temples

When Ptolemy I saw that the wealth of Egypt depended on the participation of both Egyptians and Greeks in helping the economic progress and stability of the country, he found a solution that would aid both cultures, Egyptian and Hellenic integrate efficiently- the worship of the gods. The kings wanted to be seen as rulers as well as pharaohs. Indeed, Ptolemy V Epiphanes was crowed at Memphis according the Egyptian tradition.

So, the history of Ancient Egypt was not lost for ever. Many of the huge temples, built by the great kings of the past, were still standing among the palms in the desert, and the traditional ritual was carried on in them. In the ancient language, to the old gods, by priests of the olden style, with white linen robes and shaven heads the religion known to the Pharaohs lived on. The divine animals: bulls and rams and crocodiles, were still fed and worshipped, old customs remembered and faithfully executed like in ages past.

It was the priesthood, mainly confined to particular families who could trace their blood lines through the generations, which now constituted the only native aristocracy present in a world of Hellenic overlords. It was to them in the prestige of their office, their corporate wealth, and their sacred learning, that the common people looked as their national guides and leaders.

Ptolemy formed a committee of Egyptian and Greek scholars to carry out his conceptual idea. The committee decided that the new religion would have at its core, a triad consisting of Isis, her son Harpocrates and Serapis (originally an Egyptian deity called Osir-Apis)

This triad was introduced to the Greeks in a Greek style and to the Egyptians in an Egyptian fashion. While Ptolemy the First established the worship of Serapis, it was Ptolemy the Third who constructed the great temple for this deity in Alexandria.

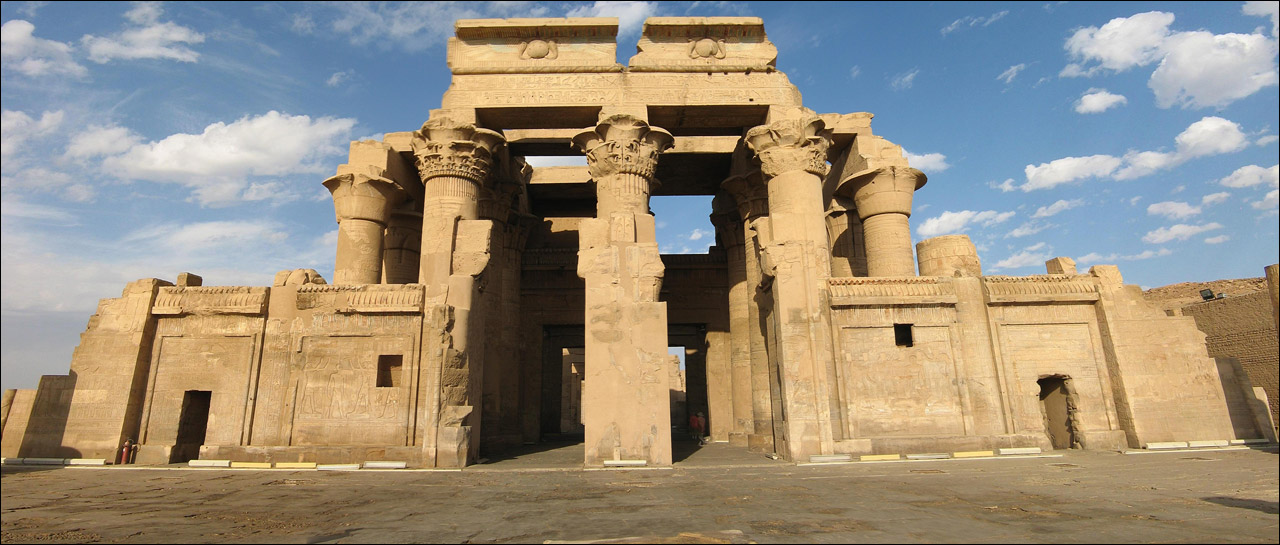

The new cult spread successfully in Egypt, and also all round the Mediterranean. During the Ptolemaic period, large temples were built at Denderah, Karnak, Edfu, and Kom Ombo to native deities to appease the original populations of the kingdom:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Edfu, the temple of Horus, founded on the site of an earlier temple, dating to the period between the reigns of Ptolemy III and Ptolemy XII 246-51 BC.

Kom Ombo, whose surviving temple buildings were dedicated to the deities Sobek and Haroeris and date mainly to the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

Philae, the temple of Isis, dating from the 30th Dynasty to the late Roman Period, and mostly constructed between the reigns of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BC) and Diocletian (284 AD-305 AD). During the early 1970's, the temple was transferred to the nearby island of Agilka in order to save it from the rising waters of Lake Nasser.

The Ptolemaic Army

Ranged

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Slingers

The commoners and the poor are most often reccruited as slingers. In an agricultural society, many shepherds become slingers, and these can find employment in an army if needed. The sling is a cheap, easy weapon to make, and stones, its ammunition, are abundant nearly everywhere. On the battlefield, the slinger is best used to strike immediately, killing as many as possible before the battle fully begins. Unlike archers, who can add an arcto their arrows, and fire their weapon close to friendly troops, care must be taken to place slingers in front of , or far enough behind the ranks, so the bullets can pass over the heads of friendly combatants. Placing them on an elevated slope or hill is ideal for this. Slingers can be devastating to the lightly armored or unprotected and little can be done to avoid the bullets once released.

The Ptolemaic slinger corps is typically behind the initial casualties that an enemy army would suffer. A slinger can strike a target from far away, killing him instantly if the bullets finds the mark. An arrow can be seen as they are released from the bow, but the sling stone is nearly invisible once launched. Many times the target is oblivious until the stones have already struck home. The intended targets have no idea where the attack originates. The bullets ricochet off the armor and shield that they carry, surprising them, and often causing them to change their order of battle so that the slingers can be dealt with.

Short messages were carved onto the bullets, denoting the owner of the bullet or a slogan such as "Take that!" or "Megacles hit you." The effective range of slingers is estimated to be in excess of 360 yards. The Romans and Greeks both have recorded that the slinger had a greater range than archers. This bullet can shatter jawbones, fracture skulls, and crack the ribs of both humans and horses. At close range they could severely injure elephants. The Romans developed a special pair of tongs designed to get bullets out of deep wounds.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Judean slingers

The Judean slinger is a basic unit in their native land. Many Judeans have a working knowledge of how to use this weapon effectively, and there is seldom shortage of slingers to be found. Typical of lightly equipped troops, their speed and flexibility is unmatched by all but cavalry, and they can rapidly advance to section of the battlefield and begin their attack which often diverts sections of the enemy army, usually cavalry, to deal with them, so this is dangerous if they are left unprotected. Light troops can only maintain hand to hand combat with other light troops. This being said, when the enemy has lost and the mop up chase begins, they are one of the best infantry you can have chase down and kill the routing foes.

Like the spearman that hails from Judea, these slingers have a loyalty that is not called into question as often as is the loyalty from other conquered lands. Their homeland remains as a tributary state under their high priests. Even when their were two claims to the Seleucid throne, Demetrias I Soter offered to minimize tribute, and lessen the poll tax and salt tax, both of which were large revenues for the king, all in order to gain the backing from these people and harvest their potential as outstanding and trustworthy warriors. The stability of this crucial region is important to maintain. The south of Judea borders with another successor kingdom of the Ptolemies, who stand ready to grab this area by force, and make new masters with these able warriors.

The Judean slinger in the Seleucid army uses his sling to pierce and smash through the defenses of the enemy in front of him, just as a shepherd has used it for thousands of years as the best way to ward away the foxes and predators that come to close to his sheep. The weapon was also used for the capture of rabbits and hares, birds, and other smaller animals. In their long history as a nation, they can look no further than to their ancient King David as a champion of their own weapon, for it was he who killed the Philistine Goliath around 990 B.C. in the valley of Elah, despite Goliath being heavily armored and shielded. This is a worthy feat and high aspiration for every Judean slinger to imitate in battle.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Archers

The Greek and Macedonian tradition of archery is and old one, and the archer is suited as part hunter and part military person, as his weapon can be used for both. The archers of other lands often place much value in the art and often produced better archers as a result. In the lands of the Greeks and Macedonians, the archer is valued, though not on the same level. They obviously rely on their arrows to kill from afar, and if they are safely behind stronger allies, their attacks can come at leisure, striking at the weakest part of a battle line, falling upon the heads of those already engaged, and targeting the cavalry that has come within the range of their bows.

The archers come form the same general stock as other light infantry. They are recruited as commoners from the population that do not have the means to forge mighty weapons or hammer out suits of armor. These things they do not need to be effective. Their own speed easily allows them to out run all enemies except cavalry, and they can easily maneuver around behind the enemy when the chance presents itself without running themselves into advanced states of fatigue like an armored warrior would no doubt feel after a long run. The archer should never fight against other infantry in hand to hand combat. If they do, then they run the risk of being eliminated unless they can successfully break off the struggle.

Diodorus states that upon the entry of Alexander in Asia proper, the number of dedicated archers could have only been around 300 by themselves. Late in 331 B.C., the army was reformed at Susa, and their numbers increases to at least 3000. This increase in the number of archers was a testament to the eastern way of war and how they proved themselves key units by their actions. By incorporating that many archers into the army, there must have been swarms of highly skilled archers all over the former Persian Empire now using their abilities for a new master and former enemy. Briso was the Macedonian commander at the victorious battle of Gaugamela. At the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 B.C. Tauron, commander of the archers, launched an offensive along with Seleucus (forebearer of the Seleucids), commander of the hypaspistai, and the two forces commenced a direct attack aimed upon Porus himself!

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Nubian archers

Nubian archers are not average archers by any means. They are recruited from a land known for its bowmen, as this style of warfare was suited for the arid environments outside the regions bordering the Nile. They march to battle , wearing only their robes, as these warriors are not usually sent into combat as melee troops. However, the animal hide shield that they keep on their arm and the axe affixed through their sash, allows them to maintain the upper hand in a melee against other archers, slingers, or skirmishers that march into war without a shield.

Polybius writing about their archery equipment, says the long bow was made of the stem of the palm-leaf, not less than four cubits in length. As for the arrows, these are armed at the tip, not with iron, but with a piece of stone, sharpened to a point, of the kind used in engraving seals. Strabo, in his Geography, writes that the Ethiopians use bows of wood four cubits long, and hardened in the fire.

The core of Nubian lands dwell south of the Ptolemaic kingdom. Though no true national border existed restricting access to either side, their homelands were generally said to begin past the 1st and 2nd cataract. The Nubians were a very warlike race. At times, they and their kingdom, centered at the great city of Meroe, were known to support the machimoi rebellions against the Ptolemaic kingdom.

Their warlike nature did not stop there, however. Strabo's account mirrors that of Dio Cassius' History of Rome, Book LIV.v.4-6. It says, "About this same time [23 B.C.] the Ethiopians, who dwell beyond Egypt, advanced as far as the city called Elephantine, with the Candace of Meroe, Amanirenas, ravaging everything they encountered." A number of Meroitic queens called Ka'andakes (Candaces) ruled Nubia-Kush just before the birth of Christ. Dio continues, "At Elephantine, however, learning that Gaius Petronius, the governor of Egypt, was already moving, they hastily retreated before he arrived, hoping to make good their escape.

But being overtaken on the road, they were defeated and thus drew him after them into their own country. There, too, he fought successfully with them, and took Napata, their capital, among other cities. This place was razed to the ground, and a garrison left at another point; for Petronius, finding himself unable either to advance farther, on account of the sand and the heat, or advantageously to remain where he was with his entire army, withdrew, taking the greater part of it with him. Thereupon the Ethiopians attacked the garrisons, but he again proceeded against them, rescued his own men, and compelled the Ka'andakes to make terms with him."

Quite interestingly, the Bible mentions a servant of the Ka'andakes (Candaces). At Acts 8:26-39, we read, "Now there was an Ethiopian eunuch, a court official of the Candace, that is, the queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of here entire treasury, who had come to Jerusalem to worship, and was returning home."

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Machimoi archers

These native contingents of archers are cheap, skilled, and rather well armed for an archer. They have small blades for up close action and are equipped with standard padded, or quilted armor which provides a lightweight form of protection in the hot environments that they are use to fighting in. Their bow, however, is where their skill really shines. As with many eastern archer traditions, they wield a composite bow, giving them extra range over their Hellenistic overlords. Despite these advantages, they do not do well in melee action, despite their daggers, and must be commanded by an observant general to keep them from any cavalry actions that can catch and devastate their ranks in a short matter of time.

Under the reign of the Ptolemies, Egyptian natives in the Ptolemaic army was a rare event, however it happened long before the battle of Raphia. In the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Diodorus mentions that Ptolemy I employed great numbers of natives in the army to fight in 312 B.C. in Gaza. The army contained 18,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry that consisted of part Macedonian and part mercenary contingent. In addition to these, its recorded that the natives filled positions within the transport service, attendants, baggage carriers, as well as soldiers within the army. Diodorus does not mention what they did in battle, but its likely they were lightly armed infantry or used in an auxiliary role. From then on, historical records and evidence are scant on the activities of the Egyptian warrior caste being used for much of anything, thought its only speculative to assume, due to their numbers, that they would have been used by the Ptolemies on a somewhat regular basis for various duties in and around the empire, despite the lack of historical records. Under the land distribution, the machimoi foot infantry, and likely archers too, received land equal to 5 auras (1 aroura = 0.7 acres). In the first century B.C. the size in some cases increased from 5 to 7 auras.

The machimoi were seemingly doomed to obscurity and living as marginal second rate citizens, that is, until the imperialistic reserves of Ptolemaic manpower became strained by the lack of newcomers from the homelands in Europe. Due to this shortage, coupled with the prospects of war looming with the Seleucids under Antiochus III, the kingdom of Ptolemy IV had no choice but to bolster his military forces with natives, who, despite their state of subjugation, were a decisive force in repelling the Seleucids at Raphia. The lands of the dark skinned peoples, called Ethiopians by the Romans and Greeks, were located to the south of the 1st and 2nd cataracts along the Nile. However, this is a generalization of the makeup and people living around the Ptolemaic kingdom and it's environs and no official border or marker defined who lived where. Many of the inhabitants from Upper and Lower Egypt no doubt traveled and settled all along the reaches of the Nile, thriving all along its banks.

As with many cultures in ancient times, archery was a given method of warfare that had existed for ages. In Egypt long before the Ptolemaic dynasty, archery was very common, perhaps more so than anywhere else in the region. Native pharaohs from times past, such as the famous Tutankhamun, have been depicted on reliefs and pictures as riding in chariots while aiming with the bow and enemies and animals. The lands to the south, in Kush or Nubia, were described as a "land of bows" by those that had seen warriors of the nearby regions or had visited there.

Hellenistic Infantry

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Akontistai

Recruited from the endless reserve of common men and those unable to afford better weapons and armor, they are trained to strike down all enemies of the their general as skirmishers before the main battle begins using the throwing javelin (akontion). Only cavalry and other skirmishers can hope to catch them, and this enables the akontistai to quickly avoid melee with stronger enemies that would easily cut them down. However, the akontistai can quickly find a position behind enemy forces already engaged in combat and can cause massive damage as they launch their javelins at them from behind. Because they are very cheap to recruit, they are ideal garrisons in cities and towns along with archers and other missile troops, helping using their long range and deadly javelins to cause harm before the enemy reaches the city walls.

Lightly armed skirmishers are not mentioned as consisting of many members of Macedonian origin. The only contingent that might have been mainly Macedonian was the group commanded by Balakros, which was not mentioned as having a specific ethnic national identity, unlike other sections of the army. Alexander was advised to keep Macedonians in the phalanx which he could rely upon to remain loyal while relying on natives and conquered peoples to fill the need for the light armed troops.

Balakros commanded the regiment of akontistai skirmishers, likely since the beginning of Alexander's campaign, at Gaugamela. Arrian writes that during the battle ,the akontistai under his command as well as the Agrianes infantry, dealt severe damage to Darius' scythed chariots with their javelins as well as taking hold of the horses reins and killing both the driver and the horses.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Peltasts

With mobility and speed of the akontistai, along with the melee ability of the theurophoroi, the peltast is one of Greece's most ancient styles of fighting, having originated in Thrace, but soon adopted all over the Hellenistic world. The peltast has been a part of the Hellenistic armies ever since. The role that the peltast fills is, prior to the main fighting, hurl their javelins toward enemy lines, in hope of disrupting their morale and formation and of course killing as many of the enemy as possible, in the shortest amount of time. They are to run back behind stronger allies in the battle line, such as the hoplites or phalanx, after their missiles are spent. From this protective spot, they can gravitate to the wings of the phalanx, and guard it from flanking and other possible disastrous event that can spell doom for the phalanx formations. As with all fast moving units, the peltast can sneak up on enemy formation in battle, launching a morale crushing assault on the rear of their formation, then darting off again before an organized reprisal can be organized against them.

In the Peloponnesian War and later in the Corinthian War, peltasts were so dexterous, that even the strengths of the hoplite could not withstand them in battle. Their effectiveness when correctly pitted against slower moving enemies is remarkable. Historically, during the battle of Sphacteria in 425 B.C. perfectly illustrates how their usefulness and utility in battle as light infantry and skirmishers bested even the resolve of mighty Spartan hoplites, causing for the first time a Spartan surrender and forever showcasing their abilities and potential deadliness when deployed and used correctly. About half a century later, the Athenian general Iphicrates nearly destroyed a Spartan phalanx during the Corinthian War using peltasts. The peltasts eventually killed about half of the 600 Spartans near the city of Lechaeum in 390 B.C. The Spartan army severely lacked their own missile troops to answer the Athenian peltats, and paid the price for it.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Ptolemaic Marines

Epibatai were the marines of Hellenic armies. According to the Decree of Themistokles, the epitabai occupied the second to highest position on the ship, second only to the trierarch, and appointed by the strategos himself to a trireme. The epibatai were part of the hyperesiai, or crews, of a ship, and were there to maintain order on board as well as to fight. Elected by lots to their station by tribe, it has been debated whether or not these were actually light marine hoplites, since both types of soldier were deployed in the same fashion.

Used for the first time in Samos. Its tyrant, Polykrates, created a unit different from the traditional hoplites manning ships. This gave the Samian navy the advantage in naval combat, as in the cramped confines of a ship, there was no room for a phalanx or to effectively fight with a spear. Swords were the primary weapon of these troops, and they were protected by helmets, round shields in the Argive fashion, and a quilted chiton. Maneuverability was their key to success. Also, the absence of any heavier armour was a blesing in diguise, since if a hoplite was thrown overboard their linothrax would suck in water, while the light chiton would not, increasing the soldier's chance of survival. Their shield was their main armor, and covered in bronze, it was almost missile proof.

When attacking, the epitabai would be deployed on the armored sides of the ship and then attempt to jump on their target vessel. For defending, the kataphraktoi trireis (cataphract triremes) came into use. With its heavily armored stern, the epitabai were virtually untouchable to enemy archers.

While very mobile and useful troops, marines should not be entrusted to hold against heavier troops in critical sections of the line, or to survive long against heavy cavalry.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

katoikoi phalangites

Katoikoi are settlers and landowners, primarily of Greek and Macedonian heritage, that are given portions of land to settle in return for military service should the king call upon them. They are primarily reservists, not professional soldiers. They are trained to form the phalanx, and their training is standard, allowing them to hold their own in battle with many of the enemies that they will march against. They are more privileged than the natives and so is their training, pay, and crafted armor and weapons; such as a small shield (pelte), leg guards (knemides), linothorax armor, and helmet. Due to their enlistment in the Ptolemaic military being at random, they are not on the same level as the professionals in the kleruchoi agema. As with all phalanxes, the primary strength behind theirs is simple: Cohesion and maintaining a solid formation. As they fight, they are usually unaware of what going on around them and behind their position. Because of this, they need to be free of being flank attacked or attacked from the rear or they will loose their solid formation and may run from the battlefield.

The terms for landowner (kleruchoi) and settler (katoikoi) would change with the times. Before the 3rd century B.C., the Greek and Macedonian land holders were referred to as kleruchoi. Starting with successes at Raphia and the demands for greater say in the running of their homelands, the natives were being granted land ownership too. In 197 B.C. during the reign of Ptolemy V Ephiphanes the natives were used in more substantial roles within the empire and were increasingly granted land allotments themselves; attaining kleruchoi status themselves. In response to this the Greek and Macedonian land holders, and perhaps other European settlers like the Celts and Thracians, increasingly chose to be called katoikoi, not kleruchoi, to distinguish themselves from native kleruchoi.

In the early Ptolemaic kingdom the majority of settlers in the military settlements (katoikiai) were Greek and Macedonian. By the mid 3rd century B.C. the majority of Greek and Macedonian settlers had all but stopped. This forced the kingdom to rely more and more upon non Hellenistic Europeans like Thracians and Gauls, mercenaries, Egyptian natives, and Asiatics to maintain the kingdom's offensive and defensive abilities as illustrated by the mass hiring of mercenaries leading up to, and after, Raphia and Panium. The largest concentration of these military settlers was in the Fayum but many still were scattered throughout the kingdom. These settlers were given a plot of land (kleros) which was usually in more rural areas or on the outskirts of preexisting towns and villages. Many of the settlements contained basic settler facilities such as the village scribe (komogrammataeus), komarch (village elder), epistates (village superintendant), the force of policemen (phylakites) and the head of police (archiphylakites), grain official (sitologos), local granary (thesauros), bank (trapeza), central registry grain office (ergasterion), the gymnasium, and of course a prison (desmoterion). Though farming and cultivation was the overall focus of Ptolemaic settlers, qualified and skilled ones could also spend their day to day life involved various duties like collecting taxes, garrisoning forts, policing their settlement, teaching in the schools, artistry, marble cutting, and filling government positions as messengers and lawyers. Other skilled settlers could further provided the means for crafting and repairing new armor and weapons, while the agriculture, produce, and taxes from their land helped keep both granaries and the royal coffers full.

In Egypt the land was measured in arourai (1 aroura = 0.7 acres). The size depended upon rank. The land that the Royal Guard received is unknown but officers could hold land over 100 auras while cavalrymen could have land the size of 70 auras. Privates in the military received land of 30 auras, while the native Egyptian was fortunate to have land over 7 arourai with 5 being the standard. Initially, the land in the Ptolemaic kingdom belonged to the king and he kept the final say on the land and this was how it was throughout the majority of Ptolemaic reign. Under this land distribution system, Egypt was divided into about 40 counties or administrative districts (nomes) which had subdistricts (toparchia) under an overseer (toparches). Land was divided into two general categories; royal land (basilike ge) worked by royal farmers who leased the land by an annual rent payment and remittent land (ge en aphesei) and remitted land. Remitted land was kleruch owned land (klerouchike ge) which was further divided by the land allotments (kleroi); temple land (heira ge) for the priesthood; gift land (ge en doreai) for servants of the king in governmental capacities such as governors; private land (idioktetos ge) held by private individuals; and city land (politike ge) which was land falling under the Greek cities in Egypt. For the settlers who worked in their allotment, they would also receive a separate plot for their personal home (strathmos). They do not pay rent but do pay certain taxes. Many settlers did not work the land themselves but instead leased it to the Egyptian natives while they lived as absentee landlords. In the early kingdom, upon the death of the kleruch, the king would reclaim the land as royal land. The king could then grant the land to the kleruch's son(s) only if they could bear arms. By the 2nd century B.C. theres mention of the land being ceded to others without crown intervention, but the new owners would take up any debts, taxes, or other preexisting expenses of the land. A law of Ptolemy VII in 118 B.C. says that if the land owner dies without a legal or valid will, that land can go to the next of kin, again, without being first reclaimed by the crown. Regardless of the condition or circumstances, however, the crown still kept a tight hold on the final say of the land. A popular tactic for the kings to keep settlers and encouraging settlement stability were tax exemptions (ateleia), granted for a certain amount of time. In Egypt, cultivators of dry or flooded land were given ateleia of 5 years with a partial 3 year exemption included. Antiochus III of the Seleucids offered a 2 to 5 year ateleia after taking Jerusalem with the goal that it would be resettled rapidly, with a 3 year ateleia for those already there and those that were willing to return to the city.

Comparing the Ptolemaic and Seleucid uses of land, military colonies (katoikiai), and the settlers shows some main differences. The policy of both no doubt dealt with the establishment of a colony being settled by Hellenistic settlers first and all others second with few exceptions. Land owners under the Ptolemies had to fight if called upon, as it was obligatory, and only males who could bear arms usually inherited the land. With the Seleucids there is no strong evidence that landowners had a duty to respond to a call up by the king and evidence of women, who obviously were not soldiers, were able to inherit a kleros. Colonists in the Seleucid Kingdom were concentrated in small settlements with either a civilian focus, or a military focus such as Asia Minor where many military settlements were founded to prevent takeover from the forces of Ptolemaic Egypt, Galatia, Pergamon, Bythinia, and others. In contrast the colonists in Egypt were often spread out all over the country as arable land was not overly abundant and, financially speaking, it was cheaper to colonize near or next to existing native towns and villages. Many Egyptian katoikiai were located around sources of water like the Nile or Lake Meoris, the latter being within reach of the Fayum settlers, where irrigation and precious water sources could be best put to use in the arid environment.

The use of land ultimately varied across the Hellenistic world. Obviously the more productive land was taken first, or land nearest to a town. Other fragmentary sources, such as the RC 51, could point to larger plots, or kleroi, assigned to the veterans and those that had the longer lengths of service. Other experts think that year round soldiers received larger lands, while those that only served part of the year, such as ones that left or the winter, received smaller plots, while another speculation is that soldiers living in the barracks were granted the larger kleroi and those in the city smaller kleroi. Later settlers would have no alternative than to choose cheaper lands located farther out from the hub of the local town or village. The Black Corcyra inscription mentions a distinction between settler who arrived first, and those arriving last, in a settlement in Illyria. According to Xenophon, land near Athens was considerably more valuable than land near Laurium (in southern Attica). Herodotus recorded the Persian distribution of Milesian land as follows: the Persians kept that land about the city and in the plains for themselves, but gave the highlands to the Carians. Diodorius mentioned that a group from Sybaris, when founding the colony of Thurii, began filling the best places of land, temple duties for themselves and ones designated for women given only to their wives to fill, and left the distant plots of land for the newcomers. After these original Sybarites were massacred, then land was resettled after new settlers were attracted and distributed on a more fair and even basis. Land nearest to the city was often the last to be attacked, while land on the outskirts was the first. In the second Messianian War, the Spartan lands near the war zone suffered heavily from collateral damage to the war at the hands of the raiding Messianians. According to Pausainius, a revolution occurred headed by the landowners that suffered these raids. Thucydides mentioned that in Athens, the Acharnian land owners complained to the Athenians about their lands being the main areas ravaged by the Spartans! In all these cases, the advantages of having land closer to cities or towns is well illustrated.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Pezoi

The phalanx consisting of Macedonian soldiers are the without a doubt the strong backbone of the Hellenistic war machine. All equipment they carry is of excellent quality; from their pike (sarissa) that averaged 18 feet or longer, to their shield (pelte), as well as their leg protectors (knemides). With this equipment they are perfectly outfitted for the rigors of battle. As they would typically be raised in emergencies, the pezoi perform similar to their katoikoi counterparts in battle as both are phalangites, but the pezoi are strictly composed of Macedonians, not others. As such they represent the memory and heritage of the proud phalangites that marched under Alexander and are expected to live up to that reputation in battle. As long as their formation remains intact, and as long as no other soldiers or cavalry are allowed to attack their flanks or get behind their lines, these phalangites are almost unstoppable and always dependable. They are not only masters at wielding the sarissa, but they also have learned how to melee with their swords as well as giving them some hand to hand offensive power, but the phalanx formation is where their strength is best put to use.

Pezoi, by definition, basically means "foot soldier," and was the term generally applied to all Ptolemaic phalangites. The Makedonikoi phallangita of the Seleucids, pezoi of the Ptolemies, and the pezhetairoi of Macedonia are all from the same background. Entire regiments of phalangites made up of Macedonians are now found only in Macedonia. Outside Macedonia the successors still field phalangites made of many Macedonians, but only the Companion cavalry and Royal Guard regiments can truly claim to be all or predominately Macedonianin in race. Other Macedonian settlers now form a large element within the ranks of the katoikio and kleruchoi agema. In Ptolemy IV's time, the term "Macedonian" no longer means those of the Macedonian race.

As the book House of Ptolemy explains: "The regular army, as a whole, was always nominally "Macedonian," but it came, as a matter of fact, to be composed of many elements beside the Macedonian. Some of it was recruited from among the Graeco-Macedonian citizens of Alexandria or Ptolemais. The great majority of regular soldiers, other than those of Macedonian blood, were Greeks or men of the Balkan hill-country. The Thracians were seemingly the largest element after the Macedonians, and, amongst the Greeks, the Cretans. There was a small proportion of Asiatics, including Jews." If regiments of pure Macedonian pezoi were to be raised then these would typically be in times of extreme emergency. The professional standing army made up of the kleruchoi agema, the Royal Guard, the cavalry, and mercenaries would be sent out first to face any threats.

Once the steady stream of Macedonian and Greek settlers had virtually stopped by Ptolemy IV's reign, the kingdom was forced to rely heavily on machimoi, non Hellenistic Europeans, other foreigners, and mercenaries to fill it's military requirements. Despite this, the Macedonians were still the essential premier soldiers. The phalangites were still arranged in chiliarchies, denoted by individual numbers to differentiate one chiliarchy from another, as they were in Alexander's day as pezhetairoi. At the decisive battle between the Ptolemies and Seleucids at Raphia in 217 B.C., the phalangites of the Greco-Macedonian pezoi and katoikoi of Ptolemy numbered around 28,000 strong and were under the command of Andromachus and another Ptolemy (not king Ptolemy IV). In addition to this powerful phalanx, 20,000 machimoi, were trained and present during this battle. The Ptolemies outnumbered the Seleucids in numbers of their phalangites which obviously gave the Ptolemies the advantage in that respect. The Ptolemaic phalangites were in the center, as was the Seleucid phalangites which also featured the argyraspides. The Ptolemaic phalangites were able to overcome their Seleucid counterparts, in part, due to Ptolemy IV's timely and inspirational arrival by his troops. In 200 B.C. at Panion, the Seleucids got the upper hand against the forces of Egypt. Here the Ptolemies and their phalanx were met with a major reverse and were defeated. Their Aetolian cavalry was driven away by the Seleucid elephants that were sent against them. The cataphracts of the Seleucids, along with their elephants, were able to get behind the Ptolemaic lines and disperse them with heavy losses. 10,000 soldiers fled with their commander, Scopas, into nearby Sidon. When the Ptolemaic forces sent to relieve the siege failed, it held out until 198 B.C. and was forced into capitulation due to famine. Scopas was able to leave honorably (found in Greece recruiting more mercenaries for Ptolemy V afterwards). In 197 B.C., the last bastion strong Ptolemaic resistance was defeated at Gaza, and this ended the Fifth Syrian War in favor of the Seleucid kingdom. Total losses suffered during that war is regarded as a strong factor to the sharp drop in the numbers of Macedonians fielded by the Ptolemies from that point on.

In earlier times, the Macedonian soldiers were recruited by territory, in which provinces all over Macedonia provided a single regiment (taxies) of soldiers under their commander (taxiarchos). Each regiment was usually around 1,500 men each, and when possible, their own commanders would be from the exact same home province as well, creating a strong feeling of camaraderie to each other, their taxies, and commander. Though settlements in Egypt often contained many people from different backgrounds, its possible that in wartime the pezoi would be kept with their regional groups, such as Phillip and Alexander had done originally. Once deployed, the men at the very front ranks where battle would begin and be the thickest would be the most heavily armored, with those towards the back sometimes having a bit less armor than those at the front and propelling the phalanx forward. Usually the phalanx would be arranged 16 ranks deep.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Kleruchoi agema

These soldiers are the best of the katoikoi in the Ptolemaic kingdom. They remain armed as phalangites are and are becoming a increasingly common sight on the battlefield due to their growing numbers. As an elite regiment both their equipment and training originates from the court of the king himself. This implies a higher degree of training, access to royal armories, and the kingdom's best weapon smiths and armor smiths to attend to these soldiers for any repairs or craftsmanship. Their privileged position gives these phalangites training under the best drillmasters employing the tried and true methods of war that have served the Hellenistic kingdoms for many generations. No matter what actions they are called for in battle or where they are stationed, these men make excellent troops for Ptolemaic generals to have at their disposal. The kleruchoi agema help form the an ever growing number within the offensive line of the Ptolemaic army as these soldiers are primarily Greco-Macedonians but also other other nationalities found within the kingdom.

While many men of the kleruchoi agema are mostly Macedonians and Greeks, some descend from the other nationalities, like Persians and Libyans, finding successes with their kleros as well and are recruited to fight in the Macedonian fashion as phalangites. As generations go by, the machimoi themselves would receive larger land grants and be eligible to be recruited into the ranks of the kleruchoi agema. Due to the efficient running and organization of their land, they've been able to carve out respectable sized estates for themselves and their family, thus providing a steady means of income for the household, as well as agricultural produce to market and revenues to fill the royal coffers. Setting themselves apart from the common pool of katoikoi phalangites, many live outside their kleros leaving the domestic and agricultural work to the natives that lease their land. Each of the settlers in the kleruchoi agema have achieved vast success in their own settlementsthey are able devote much more time to perfecting their deadly craft and drilling themselves and their various regiments into a tight knit and deadly force, with organization to match, as they often form much of the professional standing army along with the mercenaries, the cavalry, and the Royal Guard.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Thureophoroi

These soldiers are the next offensive and defensive step up from the peltast, being more versatile and equipped to react to ever changing situations in battle. They excel in three main areas. First, these men can fight as light infantry. Due to their speed and quickness they are known for appearing on the enemies flanks or behind them and helping already engaged allies in melee. Second, thureophoroi make excellent spearmen. Repelling cavalry and driving them off is another lifesaving ability they are armed and trained for. Lastly, they can skirmish. Able to attack their enemies at a distance with their javelins, they can accompany other light troops on the front lines, and add to the missile count flying towards the enemies own soldiers. The thureophoroi can do so many duties during battle because they bridge the abilities of a hoplite and a peltast. Their mobility puts them as welcomed vanguards of the phalanx too, preventing enemy cavalry charges and attacks to the flanks and back of the phalanx. A wise general will command them in the best way that he sees fit.

Many Greek armies replaced the round shield for the thureos after the Galatians overran Northern Greece in 279 B.C. The Galatians carried a shield called a "thureos," and it is recorded that sometime after this invasion that the thureophoroi appear. At first they appear in citizen armies such as the Boiotian league, and later in the successor armies, primarily the Seleucids. Representations of troops equipped with thureoi from the Hellenistic kingdoms usually show them equipped with a single spear and two javelins, although they could have carried more than two. Other Hellenistic depictions of soldiers wearing a thureos do not actually show them wielding javelins, but a single spear, taller than its wielder. Versatile in both equipment and nature, these troops form a mobile medium infantry force, integral to the Ptolemaic forces.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Thorakitai

Thorakitai can be described as a type of heavy thureophoroi, a more refined and evolved unit, complete with a heavy armor breastplate, shield, sword, and javelins. They can fight as light troops, and skirmish easily, all the while possessing the combat training that lends them to be on par with veteran heavy infantry. Like the thureophoroi, thorakitai can perform the same roles, but are much better at doing them due to both the nature of their equipment and the training that they received. The amour they are provided with give better protection and the obvious ability to last in melee much longer. They were expensive soldiers, and because of the cost of superior equipment, citizens had to be quite wealthy to equip themselves amongst the ranks of the thorakitai. These troops were frequently deployed with the Illyrians, usually fighting between the phalanx and the light troops. Another possibility was to enlarge the size of the thureoi (and presumably strengthen it) so that it's protective value was similarly increased, albeit at the expense of mobility and cost.

They carry spears that can fend off heavy cavalry charges and overcome enemy infantry in melee. Their shields and their amour are befitting of a heavy infantry soldier, allowing them to tangle with most of the best drilled soldiers an enemy can field. The abilities of these troops are best utilized when they are placed around the flanks of the phalanx in order to stop enemy flanking actions or to flank enemy units themselves when a weakness is sensed in the lines. Best used in tandem with the lighter Thureophoroi they can prove a deadly and decisive force. Using the cover from the thureophoroi missiles they can quickly engage the enemy and maneuver deftly into dangerous positions.

These troops were designed for a combination of missile fighting, and their equipment allows them a high degree of combat function. Classical records mention thorakitai are often used to support skirmishers, and representations of Hellenistic troops sometimes show spearmen with a thureos and mail; the mail being introduced as a result of perhaps both Roman and Celtic influences upon their culture and methods of warfare. Polybius mentions of a troop type called thorakitai, or 'breastplate wearers', taking their place in the Achean and Seleucid armies. Polybius also mentions Nicomedes of Cos and Nicolaus the Aetolian taking command of the light troops of Antiochus' army, specifically the light troops armed with breastplate and shield. Distinguished from both the sarissa wielding phalanx and the lighter troops, these troops were frequently deployed beside the phalanx to discourage or fight off any flanking maneuvers, as well as supporting forward skirmish and troops on the wings of the battle line. Although they were not a common sight on the battlefield, classical Roman writers compared them and the thureophoroi with the legionary, as their armor, weapons, and equipment were very similar.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Machairaphoroi

Machairaphoroi are the Ptolemaic versions of the Romans hastatii, only in a Greek expression of the Roman warrior . Armed with a sword (xiphos), shield (thureos), helmet, and throwing spears, these warriors are light infantry useful for guarding the flanks of the phalanx and catching enemies unaware due to their speed and intense professional training. Though a newer style of warrior and a departure from the usual phalangites that the Hellenistic kingdoms traditionally fielded, the Ptolemies did adapt to this kind of mobile soldier well and were able to field legions consisting of these soldiers. Not to be confused with the thureophoroi, who are spearmen with linothorax and a thureos shield, these efficient soldiers are comparable to light or medium swordsmen that help add to the offensive capabilities of the late Ptolemaic army and a worthy addition to it's varied roster of soldiers.

The earliest reference to Ptolemaic organization along Roman lines is in 163 B.C., but the seeds of Roman influence began sometime in the reign of Ptolemy IV. Possibly it was the doings of one man, a certain Kallikles. He held the titles of head bodyguard (archesomatophylax) as well as having the title of 'instructor in tactics of the King'. Despite the reformation of the army along Roman lines, it was still important for the Ptolemaic army to maintain it's traditional skirmish and missile troops. According to Asklepiodotos, their rank and file is identical to that of a Polybian legion, with the ranks in traditional Greek terminology and having Greek names for the soldiers and general staff. The organizational aspects of these Ptolemaic legions is as follows. Machairaphoroi (sword bearers) are organized into maniples (semeia). Its important to note here that Polybius, being a mainland Greek, would spell this as semaia, while in the Ptolemaic dialect of Greek it would be spelled as semeia. The maniple is divided into two centuries (hekatontarchiai) and this was under the supervision of the 'commander of a hundred' (hekatontarchoi). The lowest attested rank are the pair of 'commanders of fifty' (pentekontarchoi) who were under the centurion and its possible that 'commanders of ten' (dekarchoi) even existed. These maniples had staff and those that were outside the general ranks, such as a herald (kerux), standard bearer (semeiophoros) and a 'file closer' (ouragos) of the maniple which was the equivalent of the Roman optio, standing behind the maniple to make sure nobody left the formation during battle.

The history of the Ptolemies and Rome is quite old. In 273 B.C the first embassy between the two lands was met with cordial greeting. Roman military men were found in Ptolemaic service in many areas of the kingdom throughout it's existence. Lucius, a Roman, was the commander of the garrison stationed at on the island of Crete during the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator. As the Roman influences grew across Asia and Africa, the Ptolemaic kingdom soon relied upon the Senate of Rome for it's most important decisions and independence against foreign threats, such as the Seleucids and internal dynastic rivalries. Using manuals and trainers from Rome, these soldiers were top notch and were likely equal to their counterparts across the Mediterranean Sea. The Kingdom of the Ptolemies and the Roman Republic never experienced pitched battles against each other and so the possible outcome of a later Ptolemaic army along Roman lines against the Roman armies they are derived from are left to the imagination.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Machairaphoroi Epilektoi

Machairaphoroi Epilektoi are a unique late era Ptolemaic soldier that has been heavily influenced by the Roman way of fighting. If there are similarities then these would be close to the Roman principes in their abilities and roles in battle. Armed with a sword (xiphos), shield (thureos), helmet, and throwing spears, these warriors are light infantry useful for guarding the flanks of the phalanx and catching enemies unaware due to their speed and intense profession training. Though this newer style of warrior is a departure from the usual phalangites that the Hellenistic kingdoms traditionally fielded, the Ptolemies did adapt to this kind of mobile soldier well and was able to field complete legions consisting of these soldiers. Not to be confused with the thorakitai, who are Hellenistic spearmen with chainmail and a thureos shield, these efficient soldiers are trained as heavily armored swordsmen that help add to the strong offensive capabilities of the late Ptolemaic army and a mainstay to it's varied roster of soldiers.

Of all depictions of the 'Romanized' infantry, such as the machairaphoroi, one a single soldier is shown wearing chainmail. Possibly this is because unless they were on campaign, acting as a guard or garrison, or set for battle, then they did not wear chainmail in other everyday activities. Interesting too, is the fact that these soldiers still wield their spears and have not switched to pila or the gladius sword.

According to Asklepiodotos, their rank and file is identical to that of a Polybian legion, with the ranks in traditional Greek terminology and having Greek names for the soldiers and general staff. The organizational aspects of these Ptolemaic legions is as follows. Machairaphoroi (sword bearers) are organized into maniples (semeia). Its important to note here that Polybius, being a mainland Greek, would spell this as semaia, while in the Ptolemaic dialect of Greek it would be spelled as semeia. The maniple is divided into two centuries (hekatontarchiai) and this was under the supervision of the 'commander of a hundred' (hekatontarchoi). The lowest attested rank are the a pair of 'commanders of fifty' (pentekontarchoi) were under the centurion and its possible that 'commanders of ten' (dekarchoi) even existed. These maniples had staff and those that were outside the general ranks, such as a herald (kerux), standard bearer (semeiophoros) and a 'file closer' (ouragos) of the maniple which was the equivalent of the Roman optio, standing behind the maniple to make sure nobody left the formation during battle.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Epilektoi Basilikou Agematos

The king's own personal guard, the epilektoi basilikon agematos, are the supreme melee force in the Ptolemaic army. Armed with a thureos shield, helmet, greaves, a sword at his side, and chainmail armor, the king's Royal Guard are deadly soldiers on the battlefield. They accompany the phalanx into battle, often stationed on either flank, to help guard against any threats aimed at the integrity of the phalanx formation. In pure offense and shock infantry roles these soldiers can perform spectacularly. They can only be equaled by the elite warriors from other civilizations. No other Ptolemaic infantry regiment can outperform these elites, and of other nations, few can match them.

These soldiers would be recruited and trained from the best warriors across the spectrum of wealthy and successful Hellenic settlers from the kleruchoi agema and katoikoi phalanx, and perhaps their able bodied sons as well. As a true body of warriors with actual interests in the out come of a battle, the agema is expected to perform in battle as a true strike force. In this, they seldom disappoint as a devastating loss in a major battle could spell out the end to their own privileged way of way of life. As the highest paid men in the kingdom's standing army, these warriors are loyal citizens of the kingdom and to the king himself. Though its unknown how large the land and estates were that these soldiers possessed, the average officer in the army could receive 100 auras (1 aroura = 0.7 acres) or more, so it's likely that if these soldiers had at least that much, if not more. At Raphia Polybius mentions these elites forming a total force of about 3,000 soldiers, commanded by Eurylochus of Magnesia.

Hellenistic Cavalry

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Lonchophoroi

Not all heavy cavalry consisted of the hetairoi. Another notable type, the lonchophoroi, are the sturdy medium cavalry of Macedonian origin consisting of the wealthier nobleman who were trained to formed a sturdy unit of cavalry. These cavalrymen were available and used by the successors after Alexander. Their primary purpose was as shock troops, crashing into the enemy lines trying to breach them, hoping to cause a rout. They are armed with the cavalry lance, linothorax with scales, and a round heavy shield. Cheaper than the Companions or other Macedonian heavy cavalry, but still able to pack a real punch as they charge into enemy formations, they fill a vital role in the order of battle. While many cavalry have to charge, retreat, and charge again, well trained lonchophoroi simply need a good charge to allow their melee abilities to further expand the gap in enemy formations. As with all cavalry, use caution around spearmen, even weaker ones.

Like other heavy cavalry, they can provide shock value at the onset of battle coupled with the melee skill to stay fighting longer than light cavalry but not as long as heavy cavalry can melee. These riders are not as heavily armored as hetairoi or the cataphracts. This makes them much faster in the chase, though not as fast as light cavalry which have little or no armor weighing them down. In a close combat situation the lonchophoroi are a good balance in performance and abilities between the heaviest cavalry and the medium and light cavalry. Like the xystophoroi, these are also ideal on scouting missions, as they all possess the quick speed and strong muscle to fight there way through an ambush and if caught far from friendly forces and can hold their own when required.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Aspidophoroi

Aspidophoroi are a wing of heavy cavalry that use javelins to skirmish as a primary weapon. They can be compared to a heavier version of the Tarantine style skirmishing cavalry overall in their abilities. Once they have inflicted initial skirmishing casualties on the enemies of the Ptolemaic Kingdom with their javelins, they can opt to switch to their swords and begin slaughtering the target at close range or initiate a charge to disrupt and smash enemy formations with solid single handed lances. As great all-round cavalry, these riders are able to skirmish and melee with heavily armed enemies both mounted and on foot due to their armor and their aspis shield. Against the elite cavalry the hetairoi or the massively armored cataphracts of the Seleucids, they may not have the ability to overcome these powerful cavalry wings without support from other cavarly or infantry suited for the task.

Cavalry in the later time periods after Alexander was no longer used mainly for the hammer and anvil tactic that served Alexander so well against the Persians. Cavarlymen from the Hellenistic powers, such as the Macedonians and Ptolemies, were trained to combine functions of skimishing and melee and along with this they were equipped with defenses that would grant them more protection than normal in melee. Thus, the best cavalrymen trained for this can make a surprising statement on the battlefield by warding off skirmisher foot and cavalry while still being the bane of phalanxes if they can get around the flanks to threaten the phalanx. Commanders should be quick to use them in both roles to achieve the upper hand on the battlefield!

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Xystophoroi

Great all around cavalry, the Macedonians that form this branch of the Ptolemaic armies are well trained and experienced horsemen. In the many battles in which they will fight, their role is often dictated by the performance of the phalanx units that accompany them. The phalanx will hold the enemy line, locking it into combat and preventing it from escaping easily. The xystophoroi will wheel around and position themselves behind the enemy and await the signal from their commander. Once given, they ready their lance and charge deep into enemy formations. The carnage caused by their xyston is immense, impaling all that are unfortunate enough to stand in their paths. They are heavily reliant on the phalanx to pin down the enemy troops as, like any cavalry unit, they are vulnerable to spearmen and opposing phalanx troops.

As heavy cavalry armed in the traditional Macedonian fashion, the xystophoroi are armed with the xyston, a lance that reaches about three meters in length. For protection they equip themselves with a crafted cuirass as strong defensive body armor. These are numerous heavy cavalry, and continue the traditional role laid out for them by Philip and Alexander the Great, which is executed with a strike of great ferocity into the flanks or rear of the enemy lines, while the phalanx locks them in combat from the front. These men are tough and skilled, some of the best heavy cavalry in the world, essential troops for the Ptolemaic general to have at his command

Like other heavy cavalry, they can provide shock value at the onset of battle coupled with the melee skill to stay fighting longer than light cavalry but not as long as heavy cavalry can melee. These riders are not as heavily armored as hetairoi or the cataphracts. This makes them much faster in the chase, though not as fast as light cavalry which often have little or no armor weighing them down, and they usually end up being less fatigued after a hard fight comes to a close. They are a good balance in performance and abilities between the heaviest cavalry and the medium and lighter cavalry forces. Xystophoroi are also ideal on scouting missions, as they all possess the quick speed and strong muscle to fight there way through an ambush and if caught far from friendly forces and can hold their own quite well.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Hetairoi

The most prestigious of the mounted troops were the hetairoi (companions). The Companions are renowned across the Hellenistic world as the cavalry of Alexander and the Seleucid kings. Their unmatched courage, their superior armor and weapons, and their powerful, devastating charge can collapse the determination of the most fearsome enemy, and turn a dire situation on the battlefield into an advantageous one. No matter where they attack, the enemy will pay a fearsome price against these powerful warriors of the Seleucid heavy cavalry.

The companion cavalry would go through many changes from it's beginnings before Alexander and through to the Ptolemies. It had its origins in the retainers kept by the rulers of Macedon. In the beginning, only the nobility had the privilege to be recruited and serve in this prestigious part of the military. Only part of these were selected among Macedonian nobles. Others were recruited from Thessaly and other parts of the Greek world. Under Philip II and his expansion of the Macedonian military, the strength of the hetairoi more than quadrupled, going from around 600 in Macedonia to over 3000 riders, especially after seizing the gold mines of the Greek town Crenides, which he renamed Phillipi. This gold surplus enabled him to feed and increase his military manpower and resources. At the crossing of the Hellespont, Alexander brought around 1,800 hetairoi while it's believed the remaining 1,200 or so were left under the command of Antipater, appointee of Alexander to rule Macedonia in his absence. These were divided into eight squadrons (ilai), of about 200 riders. Each squadron would have been mostly recruited from the same regions, and commanded by captains of that home region. An exception to the rule of division was the the royal squadron (basilike ile or agema) which had a strength of 300 to 400 cavalrymen, although some sources list this group as possibly having 250 men. The riders of this group are the men that rode and accompanied Alexander himself. Usually a scouting force of 900 prodromoi and Paeonian cavalry would often lend support to the hetairoi on campaign.

Many battles featured the devastating use of these Companions in Alexander's time, most notably under the command of Alexander himself, where they proved decisive at Issus in 333 B.C.E. and at Gaugamela in 331 B.C.E. Philotas, son of renown general Parmenion, was a commander of the Companions, all eight squadrons, and answered to Alexander himself. After his death, other popular figure commanded the Companions, and these include Black Kletius and Hephaistion who, between them, split up the hetairoi under their command, Koinos, Hephaistion, Krateros, Perdiccas, White Kletius, Demetrius, and a Thracian named Eumenes son of Hieronymos.

In the era of the Ptolemies these companion styled horsemen were still extremely valuable in any battle. Much of the Ptolemaic army was organized as Alexander's was. Despite the Roman influence upon the later Ptolemaic army, the cavalry stayed Greco-Macedonian in organization, just as Alexander had used generations before. Cavalry organized into squadrons (ilai) of around 250 men were still used, with two squadrons making up one hipparchy. The commanders of each wing would typically be from the same regions as those they would command. The wedge formation was likely a common formation. Well equipped, the hetairoi used their prime weapon, the xyston, a lance up to 12 feet long made of cornel wood, to great effect. When their xyston had done its work in the charge, these horsemen brought into battle a strong straight sword, the kopis, which had an abrupt curve to it and is excellent for downward slashing at infantry below or stabbing with the point. In addition to their weaponry they wear a strong bronze cuirass, chainmail, or even plate armor to make their utility in battle complete. At Raphia in 217 B.C., the horse guard of Ptolemy IV was mentioned as being made up of around 700 cavalrymen.

Thracian

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Thracian falxmen

From far away Thrace comes these valuable warriors, no doubt eager for the fight. Wielding their traditional weapon, the falx, these settlers do not fight as phalangites. They stay true to their native Thracian style of fighting, moving in and out the the enemy ranks with agility and speed befitting lightly armored troops. With their deadly falx, they are excellent soldiers to exploit gaps within the phalanx formations and help their side achieve victory.

Starting out as mercenaries, many of these Thracians have settled under the shadow of the Ptolemies and now they and their descendants call the land of the pharaohs home. Many are equipped in their native fashion, while some become one with the cultures and language of their new homes and take up the Macedonian way of fighting and join the settler phalanx regiments. Those that have kept true to their roots are armed with the equipment of their fathers, and ancestors before them, with the frightening mask that is typical of their ancestral homelands in Europe, and most of all, the falx; a curved sword with an inner blade able to take of an arm, pull a shield away, and severs body parts with ease. Against the phalanx, these Thracians can potentially break through all the the most experienced phalangites. This causes them to become tactical nightmares when faced as the phalanx lacks the speed and mobility to counter them if they attack from the flank or rear.

The settlers and colonizers the the Hellenistic world often had much to do in newly conquered lands. They ran their businesses and built the schools and gymnasiums that were a given in any Hellenistic settlement. The katoikoi consisted of the actual Greek and Macedonians from their homelands, as well as Celtic, Thracian, Persian, Jewish, and others that went abroad after the Macedonians expanded into Egypt, settling on foreign land, and providing the successors with a ready pool of soldiers obliged to fight for them. By Ptolemy IV's reign, this steady stream of settlers had virtually dried up. This forced the kingdom to rely heavily on the natives, foreigners, non Hellenistic Europeans, and mercenaries to shore up the kingdom's offensive and defensive abilities. Since Ptolemy IV had to hire new mercenaries from the Aegean for fighting at Raphia, it seems that Greek immigration, at least those that were potentially soldier material, stopped by the middle of the 3rd century. In peacetime, they formed what could be considered a minor aristocracy within the local areas and many lived a life spent enjoying a privileged status over the native inhabitants. Day to day life of these Thracians involved duties like collecting taxes, garrisoning forts, policing their settlement, teaching in the schools, artistry, marble cutting, and filling government positions as a scribe, messenger, judge, lawyer, clerks, and mayor, positions that were formerly filled by the natives. Unrest and revolts having to do with the katoikoi settlers were not very common and they were dependable settlers in their assigned regions.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Thracian heavy falxmen